Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 64, no. 2 (Autumn 2020), pgs. 31–35

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Shook, Coyote. “30 Beautiful Heads: Return to Oz Through a Disability Lens.” Baum Bugle 64, no. 2 (2020): 31–35.

MLA 9th ed.:

Shook, Coyote. “30 Beautiful Heads: Return to Oz Through a Disability Lens.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 64, no. 2, 2020, pp. 31–35.

If they were asked to point to the “heart” of Oz, many fans would immediately point to the Emerald City on the map introduced in 1914’s Tik-Tok of Oz. Small, sparkling green, and geographically central, the pulsing metropolis unifies the different geographies and ecosystems of the various realms of Baum’s wonderland. If, however, one were asked to point to the “heart” of America, the target would be wider. One might point to the South Dakota plains where Baum lived for several years and set his lesser-known stories “Mr. Woodchuck,” “Prairie Dog Town,” and “The Enchanted Buffalo.”[1] One might point to the Kansas veldt where Dorothy found joy in the depressing, vast greyness until a tornado dropped her into Munchkin country. One might also point to Wisconsin, site of Michael Lesy’s 1973 Wisconsin Death Trip. Regardless of where you pointed, someone would likely agree with you. These heartlands, both Ozian and American, overlap in the 1985 cult classic Return to Oz.

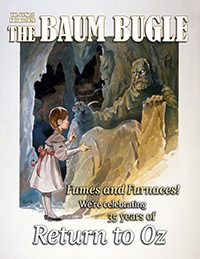

Divisive among critics for its darker tone that differs sharply from the colorful lullaby leagues and lollipop guilds of the 1939 film, Return to Oz challenges what the interrelated American and Ozian “heartlands” mean. Influenced at least in part by Lesy’s book of madness and mayhem, the film examines questions of disability and body. However, the film is more nuanced for disabled viewers than one might initially expect. Unlike popular tropes in film and literature that regulate the sick, the mentally ill, and the disabled to “villain” or “tragic hero” categories designed to elicit either fear or sympathy for diabled characters, Return to Oz instead positions fixations on “the Heartland mythology” and a cultural obsession with “cure” and beauty as the true enemy. By assembling a heroic team of disabled characters who ultimately reject both “cure” and “the Heartland” myth, the film became something deeply complex and fascinating for many disabled viewers (myself included).

Returning

As a disabled child, I absolutely loved Return to Oz. Though technically forbidden from watching it after my mother reacted less than enthusiastically to a disembodied Mombi head shouting “DOROTHY GALE,”[2] I secretly watched my VHS until the tape completely wore out. Paradoxically, the film at least superficially contradicts Baum’s 1900 preface for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz noting “Having this thought in mind, the story of ‘The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’ was written solely to please children of today. It aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heartaches and nightmares are left out.”[3] Negative reviews of the film felt it was saturated with the heartaches and nightmares that Baum sought to avoid by ridding his text of the frightening morality tales that scared Victorian children into good behavior.

However, the scenes that many felt were “too scary” for children delighted me. Perhaps it could be that at that early age, I understood “scary” to explicitly mean “scary bodies,” such as the lanky Jack Pumpkinhead or the various “amputated” bodies in the film. Perhaps it could be that, as a disabled person living in a rural area, I appreciated Murch’s iconoclastic honesty about the shortcomings of the American “heartland.” Perhaps I found some identity with Dorothy’s new band of comrades who loved their own “scary bodies” despite a culture that viewed disability as something to be “fixed” or “cured.” Perhaps I simply identified with a “crazy” Dorothy whose health is called into question repeatedly as she learns to navigate a “heartland” culture that seeks to cure at all costs. Regardless, my love for this film has endured well into my adult years and still offers me some measure of the “wonderment and joy” Baum described.

As a disabled person who writes about critical disability and American histories of agriculture and citizenship, I found new love for this film when I watched it again as an adult. Disabled and “reconstructed” bodies highlight the less-than-cheery tone in Murch’s 1985 Ozian dystopia. However, disability runs steadfast through the Oz universe. To be sure, Baum’s Oz has no shortage of “disabled” and “fixed” bodies. The Tin Woodman’s entire body becomes a clinking collection of prosthetic metal after a series of mishaps with a bewitched ax. The unfortunate China milkmaid’s entire day is thrown into chaos when her frightened cow breaks off a leg and chips her elbow, whereupon Dorothy learns that mending, while a common practice within the breakable porcelain outpost of Quadling Country, makes the body less beautiful.

While “rebuilding” bodies is simply part of Oz’s whimsy in the first book, it takes on a more sinister implication in Return to Oz’s post-Vietnam world. Mental illness and the “assembled” body in Munch’s reimagination somewhat mirror Lesy’s own ambitions with Wisconsin Death Trip. Viewers of the film examine the construction and treatment of sick and “assembled” bodies throughout the film. While some (such as Jack and the Gump) happily reject the conformity of the “perfect body,” characters such as the Mombi / Nurse Wilson, and the Nome King/ Dr. Worley highlight the damaging and often scary realities of seeking perfection when it comes to bodies and holding “cure” as their ultimate goal in a culture obsessed with “health” and that innately dislikes and fears disabled people and seeks to “fix” them. They do this work in the backdrop of “heartland decay,” in which the supposedly “healthy” landscapes of the “heartland” completely fall apart. For disabled viewers, the impact is fascinating and perhaps especially frightening.

Heartland

“The heartland,” historian Kristin Hoganson notes, “serves as a symbolic center in national mythologies…References to the heartland tend to depict it as buffered and all-American: white, rural, and rooted, full of aging churchgoers, conservative voters, corn, and pigs.”[4] For lovers of the 1939 film, the concept of the “heartland” mirror’s hardscrabble, old-fashioned resilience that Hoganson describes. The backdrop of dust storms and tornadoes and the mass exodus from the plains in the Great Depression makes Dorothy’s joy in returning home all the more in line with expectations of the “heartland’s” unique durability and endurance. The Heartland, the 1939 film insists, is not dead. It simply needs a little love and appreciation. It is the “home” that Dorothy longs for in both film and book, opting to return to her family on the drought-ravaged plains rather than remain in Oz’s endlessly fascinating landscapes.

The midwest transformed in American memory in the decades since Judy Garland awoke overjoyed to be back in sepia tones. The midwestern economy fell on “hard times,” and transformed, as Hoganson described, from unsinkable heartland to “flyover country,” a monolithic expanse of cornfields, loneliness, and the husks of the American promise of prosperity for those who would farm it. Filmmakers in the 1970s and 80s, who once might have used the Kansas plains as a backdrop for an “All American” aesthetic, relied now on the midwest to serve as settings for horror movies (such as Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre and John Carpenter’s Halloween). Not to be outdone, Murch similarly leans in on the “harshness” of the Heartland as viewers in 1985 might have understood it. Vietnam, Watergate, and the economic recessions of the 1970s culminated in a national “loss of innocence.” As such, Dorothy’s Kansas is a casualty of a shift in cultural mindsets that marked a new era in American history.[5]

The leap from the collapse of the midwest in the American imagination extends to Oz and the bodies that populate both landscapes. Heartland decay was itself horrific for the American imagination because it demonstrated something lost, broken, and innately unhappy. By that mindset, Lesy’s book and the dark reimagination of Oz are extensions of anxiety about the fate of midwest. If the “heart,” is damaged, then the metaphor would insist the national “body” is itself damaged. These images of decay were a natural focus point for me as a disabled child and again as a disabled adult. By holding the “heartland” to its mythical standards of perfection, the goal to “fix” it is in itself a bad idea. As such, “fixing” the broken bodies within the heartland as part of that work is also doomed to failure.

Like its 1939 predecessor, Return to Oz begins in Kansas. However, Murch adjusts expectations with a series of shots reminiscent of The Twilight Zone. A sky speckled with stars gives way to a Dutch angle shot which disorientingly is revealed to be a mirror’s reflection. Without a word being said, it becomes clear that all is not well for Dorothy Gale, nor the Kansas Heartland. The landscape desolate in the aftermath of the tornado, Uncle Henry suffers from a phantom ailment that leaves the unfinished skeletal construction of a new farmhouse casting eering shadows on the prairie. Dorothy, now an insomniac whose predisposition to regale listeners with tales of the Emerald City, overhears that she is to be sent to a mental institution for electroshock therapy.

One hears echoes of Baum’s description of the Kansas Outback in this initial scene. “Prairie madness,” a catch-all for the range of mental illnesses that cultural memory prescribed to the isolation of “the Heartland,” permeates through midwestern literature, including the works of other plains writers like Willa Cather and Laura Ingalls Wilder. However, it is in the landscape of Murch’s Kansas that the bland, harshness of Baum’s expanses of colorless wilderness becomes an ideal backdrop for disability analysis. The same unyielding greyness that seems to surround Murch’s Dorothy certainly haunted Dorothy in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’s first chapter. Likewise, Baum personifies the impact of such an environment on those who inhabit it through Aunt Em, who transforms from a healthy, beautiful prairie wife in her youth to a grey, severe, and nervous woman in the same sentence.[6] Unlike her laughing, cheerful disposition in Baum’s world, Dorothy’s ability to find joy in such somber surroundings seems to have run out. Unable to sleep, she is wheeled off by a careworn Aunt Em to a mental hospital.

But hold on! The expectation of heartland mythology holds that the prairie is a wholesome place that strengthens bodies and minds, not destroys them. Disabled people were advised to “take the prairie cure” for tuberculosis and other chronic illnesses, and people such as Horace Greeley and Bronson Alcott mythologized the West as a “free place” without slavery, ripe for agriculture, and that would quite literally mold sturdy, dependable bodies. Similarly, the Progressive Era ideas of medicine and science (personified by Dr. Worley in the film) mandated cure, prosthetic limbs, popularized eugenics, and frequently featured painful, inhumane treatment of the mentally ill and disabled. Sickness innately challenges the imaginary healing impacts of the American heartland and is therefore a frightening concept for American viewers to handle, particularly those delighted by Dorothy’s love of the heartland in the conclusions of both the 1900 novel and 1939 film. Not unlike Lesy’s Death Trip where stories of murder and madness sit dispassionately next to silver photographs of the Wisconsin prairiefolk, this visual imagining of the heartland centers sickness, harshness, and the “breakdown” of that landscape side by side to create something that does not sit well with American understandings of the heartland.

Cure

Oz in this film is not the beautiful landscape Dorothy left. Decimated by unknown forces, Dorothy’s land of enchantment is now a post-apocalyptic scene of ruin rivaling the Kansas she just left. The Emerald City, itself a “heartland” at the center of Ozian geography, lays wasted, with its inhabitants turned to stone and patrolled by Wheelers, terrifying part human and part machine whose hands and feet are replaced with wheels. Not to be outdone, the disorientation of this new Oz is made all the more noticeable by the introduction of Princess Mombi. Herself a conflation of two characters, the witch Mombi and Princess Langwidere, Princess Mombi’s own foray into body-building offers the film one of its more terrifying moments. Her palace dilapidated, filthy, and piled high with “junk,” Princess Mombi languidly plays some stringed instrument in a hall of mirrors before showing Dorothy her own collection of thirty heads that she places on her body when the mood suits her to change them. The head that viewers see with most permanence in the film, however, is that of Nurse Wilson (Worley’s assistant at the mental hospital). Her own decapitated body, the viewer learns, sleeps headless while all the other heads rest behind their glass doors.

Like Dr. Worley’s hospital which seeks to “cure” Dorothy, Mombi’s small world seeks to “build” a perfect human. For viewers, however, this offers one of the most iconic moments of the film’s dabbling in the horror genre. Caught trying to steal the “Powder of Life” from Mombi’s cabinet, Dorothy runs to escape Mombi’s headless body while the heads scream from their glass cases. Similarly, the Nome King (played by the same actor who portrays the sinister Dr. Worley), fluctuating between a face in the mineral-dabbled geodes and stalagmites of his underground world and a rocky, human body wearing the iconic ruby slippers, seems fundamentally discontent in his own body. Like Mombi, he seeks a different body for not only himself, but those around him. Similar to Dr. Worley’s desire to use his electroshock machine to “fix” Dorothy’s mind, the Nome King “transforms” bodies into “amusing and beautiful” ornaments. In the same way that Dr. Worley’s desire to hurt his patience using his dubious electroshock machine, the Nome King is terrifying because of his single-minded focus on “cure” and “body building” around cultural expectations of a sane, healthy mind and body.

Where Dorothy rediscovers joy and heroism, it turns out, is in rejecting that pursuit. Her own comrades are themselves “assembled” from different things. Tik-Tok, the first robot literature produced, requires mechanical motivation to act and think, both achieved by making sure he is properly wound. However, this is not as easy as it might seem for Dorothy, and Tik Tok’s mechanical gears grinding to a halt make his services inconsistent and unreliable. Jack Pumpkinhead, whose hollow gourd noggin makes a perfect nest for Billina, and the Gump, a moose-like hunting trophy with a sofa for a body and leaves for “wings,” regularly fall apart only to be happily put back together in their same, clumsy order. For disabled viewers, here lies something of a fantasy world: one in which “broken” and “assembled” is not seeking a “new” body or a “cure.”

Indeed, for these characters, “cure” is not part of their vision or plan. While they do seek to restore the political and social order of Oz under the Scarecrow’s rule, “curing” or “changing” their bodies are not part of their plans[7]. Nor, notably, does the film rely on cloying ideas of disability as a hidden superpower, or of disabled people as special or sanctified. Their bodies simply are. They are sometimes inconvenient (such as Tik Tok “winding down” and Jack and Gump falling apart). However, the characters do not express any desire to be, look, or function as “able-bodied” or “able-minded” characters. Unlike Mombi’s and the Nome King’s fixation on “prettiness” and the scary, frightening harm they do in the name of “beautification,” Jack, the Gump, Tik Tok, and Dorothy create a new space for bodies and minds that innately reject both the concept of “cure” and the insistence that their bodies and minds conform to such a standard.

In the end, the tools of “beautification” are destroyed. The Nome King’s ornament room lies in ruin, as does Dr. Worley’s hospital which burned after being struck by lightning in a storm. For a disabled child, seeing the contraptions and places that attempted to force me into a “normal” body was absolutely joyous. Unlike the humbug “cures” from the 1900 book or the actual cures in the 1939 film that rewarded the Scarecrow, Tin Woodman, and Cowardly Lion, the jubilant parade through Oz where Dorothy and her “ugly” friends are celebrated, loved, and don’t give a care in the world about new bodies thrilled me. What’s more, the “beauty and cure police” are the ones who end up punished. Mombi and Nurse Wilson are carted off in cages. Worley dies trying to save his dangerous machine, and the Nome King is taken down by a simple egg. Oz’s heart, the Emerald City, again starts beating, providing a home for able-bodied and disabled bodies alike where physical and mental perfection are not the single-minded goal (or even goals at all).

That is not to say the ends tie neatly. Dorothy’s return to the American heartland ends with a sparkling new, modern farmhouse that shows signs of middle-class hope for the family. Dorothy, for her part, is expected to not talk about Oz and play happily in the yard with Toto, a bargain she quickly accepts. However, it is that complicated love that keeps me coming back to this film as an Oz lover and a disability scholar. Arguments, much like bodies themselves in this film, are not necessarily neat or easily categorized. It is this uncertainty, ambivalence, but deep and enduring love that helps me identify so strongly with Dorothy at the film’s conclusion, tapping on the mirror, and eager as ever to Return to Oz.

[1] Mark I. West, “The Dakota Fairy Tales of L. Frank Baum,” South Dakota History, vol 30, no. 1 (Spring 2000), 134-154.

[2] Return to Oz, directed by Walter Murch (1985; Disney DVD, 2004), DVD.

[3] L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Chicago: Geo. M. Hill, 1900), [5].

[4] Kristin Hoganson. The Heartland: an American History (New York: Penguin Press, 2019), 14.

[5] Natasha Zaretsky. No Direction Home: The American Family and the Fear of National Decline, 1968-1980. (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2007), 3.

[6] Baum, Wonderful Wizard, 12.

[7] Eli Clare, Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure (Duke University Press, 2017), 6.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.