DANCER IN THE DARK

Michael Sundin in Oz

by Nick Campbell

Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 64, no. 2 (Autumn 2020), pgs. 11–16

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Campbell, Nick. “Dancer in the Dark: Michael Sundin in Oz.” Baum Bugle 64, no. 2 (2020): 11–16.

MLA 9th ed.:

Campbell, Nick. “Dancer in the Dark: Michael Sundin in Oz.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 64, no. 2, 2020, pp. 11–16.

(Note: In print, this article was supplemented with photographs that have not been reproduced here.)

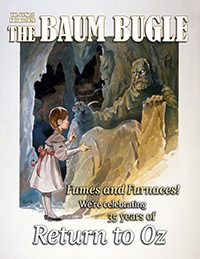

Interviewed in 2013 about Return to Oz (1985), director Walter Murch makes special mention of Michael Sundin: the 23-year-old who put the “Walking and Action” into Tik-Tok. “The further away I get from making the film, the more incredible [I find] it is, what he did,” he says. “Michael was upside-down and left to right and looking at [a screen] . . . he was seeing himself in the world from this abstract point of view.”[1]

Viewers of the film often assume that Tik-Tok’s lifelessness, which the character himself claims to value so highly, extends to the prop itself. In fact, bringing Dorothy’s four-foot, copper co-star to life took a combination of puppetry, technology, and straightforward human stamina. The history of Oz is full of dancers and acrobats—such as David Montgomery and Fred Stone, Pierre Couderc, and Ray Bolger—who contorted their bodies to fit inhuman shapes, often anonymous inside their costumes. In this case, the performer was a starry-eyed young Englishman, and Return to Oz turned out to be a key part of his career.

Born in 1961, Michael Sundin grew up in the very unstarry setting of suburban Tyne and Wear in the north-east of England. He wasted no time in somersaulting out of this rather down-to-earth part of the world, making early progress in the unusual gymnastic specialty of the trampoline. From the start, he seems to have been a committed and hardworking person, winning awards for his ability before his teens. In 1976, his team took the World Champion title for synchronized performance in the 15-to-18 Year Olds category, turning perfectly in sync in mid-air with his team partner, Carl Furrer, who later became a gold-winning Olympic medalist in the field.[2]

Perhaps Sundin might have pursued just such a sporting career. For a short time, he was on the British Men’s national trampolining squad, but he evidently had other aspirations: after leaving school at sixteen, he trained as a dancer, setting up his own dance troupe. Nonetheless, his career afterward would continue to be characterized by that gymnastic energy, discipline and stamina. His role as Tik-Tok is atypical of most of his on-screen appearances: in the music video for Culture Club’s “I’ll Tumble 4 Ya” (1983), you’ll see him cartwheeling around Boy George; that same year, in the BBC’s gaudy serial The Cleopatras, he performed standing somersaults for Marc Antony and Cleopatra. In his role in the film Forever Young (1983), he flashes back to the music scene of the 1960s, and in a drama about revolutionary France, he plays an artist’s model. He was also the “action man” presenter of the British children’s magazine show Blue Peter (see sidebar), where he was filmed stunt horse riding, undertaking “mud run” training for the Royal Marines, and riding on the back of a killer whale.

At the time he was cast in Return to Oz, Sundin was enjoying success on the West End stage in London. For two years, he performed the role of Bill Bailey in Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s Cats—only twelve months after the smash hit first opened. Bill Bailey has no musical number of his own, but he is the acrobat of the ensemble, and a friend of Michael’s at the time says the role “perfectly captured Sundin’s playful character and utilised his acrobatic dance abilities through song, dance, backflips and somersaults.” He was, they say, “an enthusiastic, kind and talented individual who was always popular, full of fun and a lover of life.”[3]

All of this must have seemed like the life of his dreams, but those dreams were about to get even bigger: he was about to take on an entirely new challenge with Murch’s crew at Elstree Studios. As Tik-Tok, Sundin was uniquely rooted to the earth, but his physical prowess was integral to his casting. He later described the experience for readers of the Blue Peter children’s annual (or an article was written from his perspective): “Tik-Tok is a very small, tubby robot, and to get inside the costume, I had to double up, bend down, tuck my head between my legs and cross my arms! Oh yes—and I had to walk backwards, as well!”[4]

According to a contemporary article focusing on the film’s technical innovations, there were actually three robot suits built for Return to Oz: one “Bright ‘n’ Shiny,” when Tik-Tok is polished for the Emerald City procession, and two “Dirties” for the dusty, increasingly battered look along the way.[5] Built of Kevlar, the suits were also routinely taken apart and repurposed across the course of filming, so that they could be manipulated to varying effect.[6] In location footage, for example, an empty suit can sometimes be seen.

Although Sundin was able to use body language to suggest limited movement in Tik-Tok’s static arms, the robot’s other features were controlled by the other credited Tik-Tok performer, puppeteer Tim Rose. Using the repurposed remote control elements of a model airplane, Rose—who, that same summer, would become forever associated with the role of Admiral Ackbar in Return of the Jedi—operated Tik-Tok’s head, along with the simple but expressive movements of his eyes and moustache.[7] The character’s voice was rerecorded later by Seán Barrett, a British actor who also vocalized creatures in Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal (1982) and Labyrinth (1986).

Walking around in Tik-Tok’s body would not be easy. “We tried many different people,” Murch says in a 2016 interview, “and many that we tried ran screaming because they couldn’t stand it!”[8] It was a role that required Sundin’s athleticism, stamina and poise. Having climbed into the bottom hemisphere of the suit, he then had to bend right over to fit inside. Boxing boots with fabric on their soles were adhered to the inside of the robot’s feet, allowing a high degree of control: like all the “creatures” of Return to Oz, Tik-Tok has a unique body language of his own, with many little proud or nervous movements, the result of close collaboration with Rose. Sundin’s arms were crossed inside the body, so that his right hand could make simple movements of the left arm and vice-versa; more complex moves were accomplished with puppeteering. For each take, Sundin performed warm up exercises “like a ballet dancer, [otherwise] I’d get unbelievably stiff by the end of the day.”[9]

“To stop me bumping into things,” Sundin told Blue Peter annual readers, “there was a small TV screen built inside Tik-Tok’s body—it took a bit of getting used to, because the picture was upside-down—but if you’re walking backwards anyway, that’s the least of your problems!”[10] He viewed the screen, which relayed an image from an outside camera, through his legs. “When you think [about] trying to process that kind of information: upside down and backwards and looking at this point of view,” Murch said, “[it was] kind of like a dream point-of-view of yourself. You dream, ‘I am here, and I’m looking at myself there, and how do I interact with the people around me…?’”[11]

Sundin even operated Tik-Tok in this complex way as he walked upstairs in the Emerald City: it was not only a feat of dexterity but courage. The effect was well worth the effort. “As a director, of course, I was thrilled,” Murch remembered. “I said ‘Fantastic, Michael, let’s do it again! And now can you do this?’ I would pile more and more [challenges] on Michael and to his eternal credit he rose to every occasion.”[12] The director even described one occasion when he found Sundin rehearsing in the suit without Tik-Tok’s head, resulting, Murch says, in a character worthy of Baum’s imagination.[13]

According to Sundin’s Blue Peter report, the costume was “excruciatingly uncomfortable.”[14] “After I’d been strapped inside with wide, webbing belts,” he told readers, “the top half of the costume was clamped down – it was just well I didn’t suffer from claustrophobia!”[15] Interviewed for the special effects journal Cinefex, mechanical effects supervisor Lyle Conway described how sometimes “in the morning, he wouldn’t be able to fit, so it was a matter of forcing him in . . . When you took the suit off of him, this rush of hot air hit you and there were pools of sweat at the bottom.”[16]

Sundin’s report emphasizes the heat from on-set lights, and the discomfort experienced by all the performers, including John Alexander as the Cowardly Lion. Giant fans were brought on between takes to cool performers down. “I even had a little fan of my own,” he says, “and my friend Fairuza used to switch it on for me when I was allowed a breather.”[17] Elsewhere in his article, Sundin describes becoming great friends with Fairuza Balk during filming; certainly, the two characters share the most screen-time of the film.

In Tik-Tok we find a machine infused by a human spirit, reflecting the task of his performers. His body language is inevitably restricted, but he is only a blank automaton when his “action” winds down. There is a restlessness to him, suggestive of a coiled spring, or a young child; among various little character moments, it is disarming to see the steadfast “Royal Army of Oz” jump when a door slams behind him in Mombi’s Hall of Mirrors. In the Blue Peter article, Sundin claims it was his idea for Tik-Tok to walk backwards: “It made him more pompous and jerky – although it was agony at the time.”[18] It is notable that Sundin’s next film appearance also required him to embody a creature half-animated by puppetry: he played a hallucination of Lewis Carroll’s March Hare to an elderly, nightmare-riven Alice Liddell in Dreamchild (1985). The Hare’s leering body language couldn’t be further from Tik-Tok. Perhaps, had things turned out otherwise, Sundin might have made a speciality of puppetry-assisted performance.

On September 13th 1984, Sundin made his debut as co-presenter of Blue Peter. The episode featured a set report on the making of Return to Oz, and viewers were told he had been “spotted” as a presenter during filming, though in fact he had auditioned several months earlier.[19] He made frequent reference to the filming experience, even discussing his trip to the New York premiere and leafing through its souvenir program: “Luckily, they were all very good reviews. I’m pleased about that.”[20] Performing Tik-Tok painted him with a little Hollywood glamour, but joining the long-running children’s program was itself somewhat prestigious and instantly granted him modest celebrity status in his native Britain.

It must have been a challenge, too. Unlike his peers, Sundin had no experience as a presenter, and was perhaps more comfortable throwing himself into the show’s various little films of unusual experiences and physical feats. Many years later, the program’s showrunner, Biddy Baxter, called him “by far the toughest person we had ever employed.”[21] Nevertheless, the decision was made to let Sundin go after his single contracted season. In their joint account of the program, Blue Peter: The Inside Story, Baxter and producer Edward Barnes claimed that viewers had not warmed to Sundin; their disdainful description of him in that book as “an effeminate whinger,” however, suggests they disapproved of him for other reasons.[22]

Our perspective on his life is necessarily distorted by the fact that, in the summer of 1989, Michael Sundin died. He was an early victim of the AIDS crisis at the tragically young age of 28. It’s an indictment of the era that his cause of death, reported in the London Times, was given as liver cancer. In October 1985, after a tabloid tried to out and shame him, he had felt compelled to deny his sexuality. Disappointments and homophobia often threaten to crowd out the achievements of his too-short life story.

Notably, after his brief spell in the papers, Sundin got back to living his life, returning to the stage in a tour of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers; then, he visited Australia and Japan in Starlight Express. He appeared in a further movie, Lionheart (1987), directed and made further appearances on TV and in music videos. He was still a young man, exploring opportunities, discovering his strengths. Were he alive and about to enter his sixties, what other adventures might he have had to reminisce about or embark upon, even now?

There is a strange poignancy in Murch’s description of the young actor inside Tik-Tok, working as if in a dream: ‘“I am here, and I’m looking at myself there, and how do I interact with the people around me . . . ?”’ Sundin was certainly living out a dream in the making of Return to Oz, and as Tik-Tok gains further generations of fans, we can be assured his is a dream that will outlive us all.

Sidebar: Blue Peter is the longest running children’s TV show in the world, and something of a cultural institution in British television. The “Blue Peter presenter” is a by-word for moral decency, authoritatively guiding viewers through any subject: from skydiving to famine in Ethiopia to making candle-holders (all of which featured alongside Sundin’s Oz report in the Blue Peter annual). They are beloved figures to their respective generation of viewers; their wholesome but informal presenting style being best likened to that of American public television hosts from the same period, such as Fred Rogers.

At the time of writing, scattered excerpts of Sundin’s time on the show are available online. You can watch him offering advice on diabetes and eggs, experimenting with radio-controlled models, and wading out to measure flood levels in a small coastal town. Oz fans are most likely to enjoy the first six minutes of the episode from January 17, 1985, featuring a performance by young dance students to Meco’s disco rendition of “Over the Rainbow.” Sundin enthuses benevolently over this surreal piece of television, after which the team watch a clip of Harold Arlen’s “Jitterbug” footage. Beaming, Sundin concludes the piece with the words, “Oz films are very fun to do . . .”[23]

[1] Walter Murch, “Operating ‘Tik-Tok’: Walter Murch remembers Michael Sundin on RETURN TO OZ,” interview by Howard Berry, The Elstree Project, uploaded January 22, 2014, http://theelstreeproject.org/2014/01/interview-excerpt-walter-murch-recalls-michael-sundins-performance-as-tik-tok/.

[2] “Michael Sundin,” Classic TV: Blue Peter, last modified June 2003, http://www.bbc.co.uk/cult/classic/bluepeter/presenters/sundin.shtml.

[3] “David P,” email to author, July 20, 2020.

[4] Untitled report in Blue Peter: Book Twenty-Two (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1985), [19].

[5] Brad Munson. “Return to Oz.” Cinefex, number 22 (June 1985), pages 26–27.

[6] Tim Rose, in “Return to Oz,” by Brad Munson, Cinefex, number 22, June 1985, page 27.

[7] Rose, in “Return to Oz,” page 27.

[8] Walter Murch, “’Upside-down, backwards and side by side’: How Tik-Tok was made,” interview by Christopher Sykes, Web of Stories, April 2016, uploaded March 29, 2017, https://www.webofstories.com/play/walter.murch/141.

[9] Blue Peter: Book Twenty-Two, [19].

[10] Blue Peter: Book Twenty-Two, [20].

[11] Murch, “Operating ‘Tik-Tok.’”

[12] Walter Murch, “A ball and two legs and it is running around,” interview by Christopher Sykes, Web of Stories, April 2016, uploaded March 29, 2017, https://www.webofstories.com/play/walter.murch/142.

[13] Walter Murch, “Ball and two legs.”

[14] Blue Peter: Book Twenty-Two, [19].

[15] Blue Peter: Book Twenty-Two, [20].

[16] Lyle Conway, in “Return to Oz,” by Brad Munson, Cinefex, no. 22 (June 1985), page 27.

[17] Blue Peter: Book Twenty-Two, [22].

[18] Blue Peter: Book Twenty-Two, [21].

[19] Richard Marson, Blue Peter: 50th Anniversary (London: Hamlyn, 2008), 108.

[20] Blue Peter, featuring Simon Groom, Janet Ellis, and Michael Sundin, aired June 24, 1985, on BBC1.

[21] Biddy Baxter and Edward Barnes, Blue Peter: The Inside Story (Letchworth, England: Ringpress, 1989), 195.

[22] Baxter and Barnes, The Inside Story, 195.

[23] Blue Peter, featuring Simon Groom, Janet Ellis, and Michael Sundin, aired January 17, 1985.

.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.