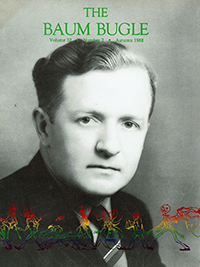

JACK SNOW AND THE LAND OF OZ

by Peter E. Hanff

Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 32, no. 2 (Autumn 1988), pgs. 10–15

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Hanff, Peter E. “Jack Snow and the Land of Oz.” Baum Bugle 32, no. 2 (1988): 10–15.

MLA 9th ed.:

Hanff, Peter E. “Jack Snow and the Land of Oz.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 32, no. 2, 1988, pp. 10–15.

(Note: In print, this article was supplemented with photographs and vintage advertising that have not been reproduced here. However, typographical errors have been left in place to accurately reflect the printed version.)

From 1900 until 1942, thirty-six different Oz books were published. Except for the first, all were published by a small Chicago firm, the Reilly & Britton Company (beginning in 1919, The Reilly & Lee Company). L. Frank Baum, who founded the series with The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900, wrote another 13 titles, publishing one a year after 1913. His last Oz book was published posthumously in 1920. Ruth Plumly Thompson continued the series from 1921 with 19 additional titles, retiring from the series with her book in 1939.

Remarkably, a single artist, John R. Neill, had illustrated all but the first Oz book, and with Ruth Plumly Thompson’s retirement, he added three titles of his own to the series. Beyond his contribution of three titles, Neill provided the series with a uniformity of appearance that helped bridge the transition from one author to the next. Only Neill’s death and the wartime economy of 1942 caused a serious disruption in the continuation of the series.

In 1946 Reilly & Lee brought out The Magical Mimics in Oz, written by Jack Snow and illustrated by Frank Kramer. This was the first Oz book with neither an author or illustrator connected with prior books in the series. Frank Kramer’s illustrations were strikingly different from those of John R. Neill, and Snow’s text was far more somber than that of any recent title in the series. The discontinuity of authorship and style of illustration, combined with the sluggish post-war economy, probably contributed to the book’s disappointing sales.

Aside from a few fragments, manuscript versions of Snow’s books apparently do not survive to help reveal the actual process of creation of his Oz books. However, copies of letters between Snow and other individuals, including those at Reilly & Lee, have been preserved, and these give an important sense of the author’s work during the years in which he wrote The Shaggy Man of Oz and Who’s Who in Oz.

In 1946 Snow began a correspondence with Edward Wagenknecht, a longtime admirer of L. Frank Baum who had written the first scholarly appreciation of Baum and the Oz books in 1929. In his letter of May 27, 1946, Snow discussed his feelings about Baum’s Oz books and told Wagenknecht about the forthcoming Magical Mimics in Oz:

The Oz books are wonderful to the point where Ruth Plumly Thompson started writing them. There they cease to have any relationship to Baum or to Oz. She stopped writing in 1940. The publisher wanted to continue them and it has been my good fortune to have been selected to cany the series on. My first Oz book, The Magical Mimics in Oz, will appear in the fall. I have gone back to where Baum left off and ignored the 19 Thompson titles. I have tried to my utmost to write the book as Baum would have told it, and honestly I have so steeped myself in the man’s life and writings that I believe I have succeeded at least partially. At any rate I will flatter myself by saying that I have done less harm to the Oz mythos than many another writer might have committed.

Although we may disagree with Snow’s assessment of Ruth Plumly Thompson’s major contribution to the Oz series, there is no argument that Snow was deeply devoted to Baum and the Baum books. In the early 1940s Snow had corresponded with numerous individuals, including several members of Baum’s family, indicating that he was gathering information for a biography of L. Frank Baum. Snow sought information about Baum and also acquired a number of books from the Baum family, forming one of the earliest private collections rich in family association interest.

In October 1946 Snow again wrote to Wagenknecht, “I do not much like Magical Mimics as a title, but it seemed the best there was. The book was long written before it was titled. Shaggy is just the opposite. I believe this will be a much better book than Mimics. I am going to do my best.”

Wagenknecht must have commented on his reading of The Magical Mimics in Oz, for in the same letter Snow continued:

I didn’t make Toto talk. Frank Baum did that in Tik-Tok of Oz. Remember? It was in the final chapter when Dorothy, Trot and Betsy were wondering how it was that Billina and Hank—ordinary United States animals—could talk when they arrived in Oz, but Toto couldn’t. Dorothy pinned her pet down and he revealed that he could talk, but had thought it wiser to remain silent. From then on through the remaining Baum books Toto talked like the other animals who came to Oz.

I agree perfectly with you on Frank Kramer’s illustrations. He had a great deal of trouble with the girls. He improved toward the end and I am sure he will do a much better job from now on. I like his animals. Also I want him to keep the Neill style but put Dorothy and the others in modern dress. That can be done, I believe.

By February 1947, Snow could report to Wagenknecht progress on The Shaggy Man of Oz, “Shaggy Man is coming along splendidly, but knowing the times and the slowness of Reilly & Lee, I shall be thankful if it is published as early as Spring 1948. It is all about the further adventures of Shaggy and his Love Magnet.”

During 1947, Snow began a lively correspondence with William G. Lee of Chicago. Lee had begun collecting Baum and Oz books seriously and Snow provided him with bibliographic information and even found books in New York book stores to send to Chicago. Although their correspondence focused on collecting rather than on the relative merits of the Oz books, in late October Snow wrote:

I’m afraid Reilly and Lee are not too enterprising. Mimics was the only book they published last year and this year to my knowledge they don’t have a single new title in their catalog. They just seem to sit back and exist on the Oz books, Eddie Guest and Ergmeier’s Illustrated Bible. I will be lucky if Shaggy Man comes into being next year. Mimics did not sell too well due to delivery troubles—they just didn’t get it into the stores in time for Christmas. But we will see.

On January 14, 1949, F. J. O’Donnell, the president of Reilly & Lee, wrote to ask Snow about progress on a proposed biography of Baum. He also inquired about the The Shaggy Man of Oz. O’Donnell indicated that of the two books, the firm would prefer the biography because they still had a large stock of Mimics on hand. Indeed O’Donnell concluded the letter, “I can’t understand why ‘Mimics’ doesn’t sell, we are still getting returns from all over the country.”

In February Snow suffered a bad fall in New York. The correspondence between January 14 and March 31, contains no letters to or from Snow. However, O’Donnell’s letter of the latter date revealed that he had just learned of Snow’s leg and ankle injuries sustained in the accident. More important to us is O’Donnell’s state-ment, “We have ‘Shaggy Man’ listed for Fall (1949) publication.” In just two and a half months the idea of publishing a Baum biography had given way to publication of a new Oz book. Still another intriguing paragraph is the last one, “Will hold the Animal Fairy Tales and the Baum Biography in abeyance until you are up and around again.” Snow had for some time hoped to see Reilly & Lee bring out a single-volume edition of Baum’s “Animal Fairy Tales,” originally published serially in The Delineator in 1905.

On April 14, Reilly & Lee editor Elizabeth Laing Stewart, who signed her correspondence “Jerry,” wrote to Snow:

You’re really a swell sport. I quaked every time I thought of your getting my letter. I really am sorry. But now I feel sure you can shuffie things around and have a fine book.

Alas, I’m afraid it will entail tossing out a lot that you have already written. In fact, I think the less you concentrate on trying to save what has been done and the more on simply writing it fresh the better it will be.

From the time the travelers get to the Valley of Romance on, I like the story, though I would suggest some changes there too. I love the idea of their living only on the escapist romance of the stage and of their changing because of the Love Magnet. That has just the overtones adult readers will enjoy and in a way children will get it too and it will be good for them without being moralistic. I’m really enthusiastic about it.

From this short segment of the letter, we can assume that other letters must have been written between Snow and Reilly & Lee between January and April. Further, we see that there had been dialogue between Jerry Stewart and Snow that led to a serious rewriting of early portions of the original manuscript. Throughout her letters Stewart revealed a genuine love of the Oz books and a good sense of the general content of those by Baum. “I keep thinking that perhaps all this is too reminiscent of the book in which they search for the Shaggy Man’s brother—at least I think that’s who it is. You’d better glance through that book again [so] you’ll be sure not to come too close to it. Is it Tik-Tok of Oz?”

It is evident that the editor was actively participating in the creation of The Shaggy Man of Oz. Whether she recognized its similarities to elements of John Dough and the Cherub is not evident in the transcripts of her letters.

Just a week later Stewart wrote to Snow that she was glad to have talked to him by telephone. Apparently he had called to say that he was having to rework the story far more substantially than either of them had projected. Stewart sympathized:

Mr. O’Donnell said his first consideration is that we have a good book. Possibly we could wait until the week of June 6 to have the script complete, but that would mean with all revision finished, etc. He said Kramer could have until July 1 for illustrations . . . How I pity your present frame of mind, trying to think up an entirely new story! It’s a shame we didn’t get together on what you had in mind for the Shaggy Man long, long ago. Of such sad mistakes is publishing!

It is also clear from the letters that Snow was forwarding his typescript to Chicago a chapter or two at a time. On May 13, Stewart acknowledged receipt of Chapter 18. She indicated that she liked the text but felt that it needed greater tension. Indeed she went on to comment that virtually all the revisions she wanted to see involved additions. She considered that fortunate, for the book was running about 27,000 words compared to 29,000 for The Magical Mimics in Oz. She indicated that other recent Oz books had run about 31,000 to 33,000 words. Stewart also reported that O’Donnell had forwarded the carbon copy of the typescript to Kramer to begin work on the illustrations. The letter concluded with comment on Stewart’s understanding that Snow was finally up and around on crutches.

On June 22, Stewart acknowledged receipt of the final part of the book. Again revealing her own interest in the Oz books, she wrote:

Before I forget it! What about Shaggy’s brother? Isn’t it sort of impolite to him not even to mention him in a book about the Shaggy Man? Maybe something happened to him in a book I haven’t read, but I supposed he would still be in Oz. I notice Baum mentioned him the first time he spoke of the Shaggy Man in the Lost Princess£but forgot all about him when he finally listed the Shaggy Man’s searching party the second time. Anyway, I don’t approve of forgetting him How about inserting just a paragraph at the beginning about the Shaggy Man going to say goodby to him or leaving him a note or something?

However, this suggestion was not incorporated into the published version of the book.

On July 7, Stewart sent Snow most of the galleys, commenting that part of Chapter 18 was still being typeset. She also revealed that the printers had changed from Century type to Caslon Oldstyle, “partly because we thought it made a better looking page and partly because it is less black and might, we thought, make the illustrations look better.”

She continued with comment about the illustrations:

I’m rather disappointed in most of them, incidentally. There are a few good ones, but there are too many in which the people look sort of wooden. And say—you were going to have him [Frank Kramer] make Tom and Twink look about twelve. On the contrary, they look barely eight! I’m sorry about that, but it can’t be helped now. If you talk to him, encourage him to do the bolder sort of drawing and not to do the characters sketchily but fully drawn and full of personality.

The same letter revealed that the editor also was concerned about the history of the Land of Oz and its correct representation in Snow’s book:

I have made a change without asking you about it and I hope it’s all right with you. I intended to write you about it because it has worried me all along, but I kept forgetting until it was too late. I think the Barrier of Invisibility Chapter should follow the one about the Flame Folk, because the Deadly Desert is not really a part of the land of Oz and the Barrier did not surround it. To be sure, I checked in The Emerald City of Oz and just a few pages from the end Glinda said, “Those who come to the edge of the desert or try to cross it, will catch no glimpse of Oz or know in what direction it lies.”

That doesn’t indicate in any way that they couldn’t see the Desert, and besides, I think it is visible in other books. Transposing the chapters and the little text to go from one to the other was no trick at all-mostly cut and paste, with just a change of a sentence or two. Anyway, you’ll see the galleys as soon as they are ready.

Clearly Snow was being confronted with an editor deeply involved in the Oz books.

A new concern manifested itself just about a month later when Stewart wrote:

I’m putting your book into pages and holding my breath for fear we won’t have enough. Mr. O’Donnell told me we would have only about four pages less of illustrations than in Magical Mimics and instead there are somewhere around twenty pages less of illustration—not just twenty less illustrations but that many less pages devoted to pictures. Meantime, your book ran long enough that I thought it would take up too much space in the Century type and liked the Caslon Oldstyle better, and didn’t want to have to cut any of your copy, so I had it set in Caslon which is a touch smaller. So the texts doesn’t take up as much space as it does in Mimics.

I haven’t finished the paging so I don’t know how bad off we are, but I may have to ask Kramer to do quite a few more illustrations. It will look swell though. Did I ever tell you publication had been postponed to October?

The combination of Snow’s serious leg injury in the winter of 1949 and the subsequent business of getting The Shaggy Man of Oz prepared for publication undoubtedly kept him fully occupied outside of his regular work at NBC. Correspondence with Lee was apparently all one-sided through most of 1949. Finally, on October 3, Snow responded to Lee:

Of course I should have written you numerous times, but ’49 has just not been one of my years, I am afraid. First off last February I fell and broke my leg and smashed my ankle to smithereens. I was in Lenox Hill Hospital for three months and came out on crutches. It was very expensive so I had to close my apartment and put all my things in storage. Upon being released from the hospital I took a room in a small hotel near NBC so I could make it to work by taxi. Then I graduated to a cane and got around better. I found an apartment near NBC and got my books out of storage. I am still there though it is frightfully expensive. I cannot walk well enough to make the subway stairs and it doesn’t seem that I will ever be without a limp.

But there is a brighter side to this lugubrious tale. While I was in the hospital Reilly and Lee wired saying they wanted an Oz book for fall publication. I wrote it—The Shaggy Man of Oz and Frank Kramer illustrated it. Should be out any day now. I thought I would have copies by this time. I am convinced it is a far better book than Mimics both in text and illustration. The story is lively and full of fun and the illustrations are fine—particularly the jacket. Just as soon as I have a copy I will put it in the mail for you.

There is a gap in the Reilly & Lee correspondence file between August and October 17, 1949, but the next letter from editor Stewart, is of great interest to us. We can continue to marvel at her involvement in the production of the book, particularly because she was so keenly connected with its content:

At last your book is on the press! Mr. O’Donnell told me about talking to you over the phone so I did not send the page proofs.

At the very last minute I discovered two things that I felt strongly needed changing, so I went ahead and did it. It seemed bad to me to have Shaggy give Conjo the love magnet to fix when from all that had been said it was clear that he (had to) have the magic compass in return. I felt there should be something to indicate that his negotiations with Conjo were not settled. So I added just a few words so that Conjo said he wanted to examine the love magnet to see if it could be repaired, and had him tell Shaggy he would let him know the next day whether it could be repaired or not. That way Conjo is jumping the gun by fixing it and taking the compass. The way it was Shaggy was really in the wrong to give him the love magnet as that implied that he would have to give him the compass. I doubt whether that is clear to you, but I think you will feel it is O.K. the way I have it in the book.

The other thing is that the beaver king had said nothing to indicate that the cloaks of visibility would enable the wearers to see the invisible as well as to be visible themselves. As it was, it seemed to me that they would not be able to see the walls of the tunnel, and that they would certainly know without speculating when they had passed the barrier. So I added just a few words to the beaver king’s speech to say that the cloaks would not only make the wearers visible but would enable them to see the invisible.

The confident and friendly tone that evolved in the letters Stewart wrote to Snow reveal that their correspondence was indeed cordial. We miss the Snow side of the letters during this period, but there is sufficient progress in those of Stewart to give a good sense of the development of the book. Even more significant is the apparent confidence Snow had in his editor to let her feel comfortable adjusting aspects of his book. The last letter of 1949 in the file is from Stewart to Snow and is dated December 12. She inquired about progress on his biography of L. Frank Baum, the subject that had begun the year’s correspondence.

A brief note from Snow to Lee on November 9 reported that The Shaggy Man of Oz was apparently on the market, although thus far Reilly & Lee had not yet sent any advance copies to Snow. Snow also mentioned that Reilly & Lee had approached him for a Baum biography in the very near future, “so that sort of shunts the Baum bibliography to some future date.” This last is apparently a reference to a proposed bibliography of Baum’s writings. Although there does not appear to be any other reference to such a work in the surviving correspondence, the intense interest in Baum’s works shared by Snow and Lee might have suggested such a project to both.

There is nothing in the Reilly & Lee file of Snow correspondence for 1950. The next letter was dated January 3, 1951, and was from F.J. O’Donnell who inquired about any progress on the L. Frank Baum biography. The next letter in the file, dated February 28, was a response to one of Snow’s dated February 12. The Snow side of the correspondence is absent from the file. This letter commented on disappointment at Reilly & Lee that a visit to Chicago by Snow to discuss the proposed biography, partially paid for by the publisher, proved unsatisfactory. That was followed by a letter in May 1950 from Snow requesting an advance on royalties. According to O’Donnell’s comments, the firm heard nothing further from Snow and finally made arrangements with a new author to “do the 1951 Oz book for us.” The same letter also alluded to Baum’s “Animal Fairy Tales” stories. Snow had supplied copies of the stories to Reilly & Lee, suggesting that they be reprinted as a book.

The correspondence file has nothing further in it until March 3, 1952. In this letter, O’Donnell explained that Reilly & Lee had decided against proceeding with the Baum biography. He wished Snow well in placing it with some other publisher. He also mentioned that the firm had decided against publishing an Oz book in 1952 and would not decide about publishing one in 1953 until later in the year. At the same time he said the firm was working on costs for manufacturing the “Animal Fairy Tales.”

The next communication in the file puts an interesting perspective on the business of writing Oz books in the early 1950s. The combined royalties paid for the year 1951 for both of Snow’s Oz books totaled $149.85. Today, most of us understand that few authors can make a living on their royalties. This was clearly the case for Snow in the 1950s.

Evidently there was further communication between Snow and the publisher, for on April 16, 1952, O’Donnell responded with information about the firm’s decision to find a new author for the 1951 Oz book. He also indicated that he would keep Snow in mind if the firm decided to publish another Oz book. He concluded the letter by mentioning the discovery of an old file, marked “Animal Fairy Tales,” that contained tear sheets of all the stories used in The Delineator. These were accompanied by a note of about 1911 in the handwriting of F. K. Reilly indicating that the stories should some day be published as a book. O’Donnell then indicated that Reilly & Lee would like Snow to write a foreword to the proposed publication.

In January 1953 O’Donnell wrote to Snow to propose a new project: an Oz dictionary or encyclopedia dealing with all the characters in the Oz books from The Wizard to The Hidden Valley. He suggested the elements that should make up such a reference work. He sought Snow’s opinion of the idea and asked if he might be willing to undertake such a project and how long it might take. The same letter also mentioned that the company had decided not to publish a new Oz book but was considering publishing one or two of the Baum “Animal Fairy Tales.”

Snow apparently responded with interest, for the next letter in the file, February 18, commented favorably on “Who’s Who in Oz, by Jack Snow in Collaboration with Professor H. M. Wogglebug, T. E., Dean of the Royal College of Oz.” Although O’Donnell still expressed some caution about the scope of such a project, his letter indicated that the firm was about to ship a complete set of the Oz books to Snow for his use.

On February 24, O’Donnell wrote again, narrowing the scope of the project, while including his sense that it would have a biographical sketch of Baum, with briefer sketches of W.W. Denslow, John R. Neill, Ruth Plumly Thompson, Snow, Rachel Cosgrove, Frank Kramer, and Dirk Gringhuis, the authors and illustrators of the Oz series.

By March 4, the date of O’Donnell’s next letter, the 38 Oz books had been shipped to Snow. In this letter, the planning of Who’s Who in Oz had progressed sufficiently for O’Donnell to state that the firm intended to reproduce the illustrations from the Oz books. They expected to use a map of Oz for the endpapers and were already working on a dust jacket design.

Snow was apparently working steadily on the project for he elicited from O’Donnell on April 15 the statement, “Through 20 of the Oz books is good news, and it is agreeable if the total characters to be illustrated number less than 100.” Things were progressing fairly rapidly and the firm had hopes of preparing presentable salesmen’s samples by early June. (On that same date, Reilly & Lee also sent Snow an accounting of his royalties for 1952: $150.70.)

Finally, at this point in the Reilly & Lee file, we find copies of letters from Snow. The first of these was dated 20 April 1953, and revealed something of Snow’s enthusiasm for the Who’s Who project. It also indicated how engaged he was in various possible marketing strategies for the book, including a suggestion for basing the dust jacket on a montage of Oz-book jackets, and using the slogan “The Happiest Who’s Who Ever Writ-ten” in the publicity. The last idea was indeed used by the·publisher.

By April 29, Snow had continued thinking about the book and had come up with a scheme to prepare an Oz alphabet, “A stands for Adventure in Oz,” to head each alphabetical section of the book. This same letter also proposed that Snow rewrite the last two or three chapters of The Sea Fairies and Sky Island to convert them to Oz books. The firm did not follow up on this proposal.

On June 8, O’Donnell wrote a brief note to explain that the lack of correspondence from him to Snow reflected the firm’s efforts to determine how best to reproduce the illustrations for Who’s Who in Oz. Because the original drawings were missing, the publisher hoped to use illustrations right from the original books. The note also mentioned that the firm had an experienced book designer working on an idea for the book.

A little over a week later, a letter from Madeleine Kilpatrick, editor at Reilly & Lee, forwarded a rough layout to Snow. This showed how they intended to handle the text of the book. She also sent along a copy of the fall Reilly & Lee catalog containing blurbs on Who’s Who. Her letter also conveyed a request that he forward any written material for the book as soon as possible.

The writing of Who’s Who in Oz progressed far more slowly than the firm had hoped. Nevertheless, a cordial correspondence between Kilpatrick (who on July 13 began addressing Snow by his first name and signing her letters “Pat”) developed. Much of her work had to do with the detailed editing necessary to keep Who’s Who in Oz as error-free as possible. She also worked through the project of the first book publication of one of Baum’s “Animal Fairy Tales,” Jaglon and the Tiger Fairies.

For this special project Reilly & Lee, in order to secure a copyright in the work, asked her to incorporate a few new characters in the material. She asked Snow to read over her work to assure that what she had done conformed reasonably well to Baum’s prose.

Work on the Oz reference book continued. By July 14, Kilpatrick could write, “Just finished proofing your copy for Who’s Who—the 80 pages which we already have here. Therefore, I have a few more changes which occurred to me as I read through the material:

p.75 of ms.: You have Humpy as stand-in for Valentino, Gable, Brando—yet Lost King was written in ’24 and published in ’25. Ought we, then, to have this reference to the latter two? Might it not be better just to say “some of the most important stars in Hollywood”—or some such?”

Such editorial work was relatively minor, but necessary to give the book integrity. Once again, Snow had a congenial editor at Reilly & Lee who had sympathy for his efforts and a concern for the quality of his work.

On July 20, Kilpatrick wrote to thank Snow enthusiastically for his suggestions on her work with Jaglon and the Tiger Fairies. Apparently he was quite willing to look over her work on the title and gave her a number of valuable suggestions for improving the book. She also mentioned to him that she saw his former editor Jerry Stewart quite frequently.

By the end of July, Snow had read still another version of Jaglon and had also responded with a number of additional corrections needed for Who’s Who. In her letter of July 31, 1953, Kilpatrick also suggested that the biographical sketches and synopses of the Oz books should run about a quarter-page each.

The letters in August 1953 suggest that the main body of the work of Who’s Who in Oz was complete, with just some of the biographical and synopsis material to be completed. During that month Snow wrote urgently to O’Donnell requesting an advance on royalties to help him secure a new, more conveniently situated apartment in New York. Snow’s move was mentioned briefly in Kilpatrick’s letter of September 2, which also stated that the preparation of Who’s Who was going well, “and with good luck and a good deal of Irish persuasion, still exerted on the printer, I feel we will make late October publication.”

On September 24, Kilpatrick wrote to Snow again, requesting a citation for “C. Bunn, Esq.” This revealed that she was still editing the typescript for I. In the same letter she also mentioned that O’Donnell had put a great deal of pressure on the artists who were retouching the illustrations for the book. She was still hopeful of meeting the November 15 deadline for publication that year.

As it turned out, her hope was in vain. The delay with preparation of the illustrations made it clear to O’Donnell that the book could not be published in time for the Christmas trade. He was also troubled by the state of the corrected typescript and arranged for it to be completely retyped so that it would be usable by the typesetters. Regrettably none of these developments were communicated to Snow who wrote to O’Donnell in late November expressing his alarm and concern at having heard nothing about the project for almost two months.

O’Donnell responded promptly to Snow’s letter on November 27, but made matters worse by carelessly referring to the retyping of the manuscript as a rewriting. He tried to excuse the long delay in communication by saying he had waited in the vain hope that they would still meet the publication deadline.

By this date, however, he could inform Snow that the book had been postponed until Spring 1954.

Despite the anxiety it caused Snow the delay almost certainly resulted in a better book. Who’s Who in Oz proved to be a handsome volume—certainly the most elaborately produced by Reilly & Lee in many years. The typography was very good and the illustrations, printed in a bright salmon-red, balanced the black of the type very well. The newly drawn endpapers showing Oz and the countries surrounding it were also very attractive. The cloth binding was sturdier than that of the Oz books and was stamped in two colors. Even the dust jacket, an adaptation of John R. Neill’s drawing for the endpapers of The Royal Book of Oz, splashed with an overlay of red and yellow, gave the book a distinctive appearance.

And Snow was pleased. On October 5, 1954, he wrote O’Donnell:

Everyone who has seen Who’s Who in Oz here is delighted and charmed. The format, design, art work and production are superlative. To me, the jacket is the most amazing thing about the book. It Is better Neill than Neill. Brentano’s have a large stack of the book—not stuck back in an alcove with the other Oz books—but on prominent display. You can well be proud of your share in the production of this book. I only hope the writing lives up to the book’s appearance.

Sadly, this was the last significant Oz project for Snow. Sales of Who’s Who in Oz, an expensive book to produce, were very slow. The royalty report for 1954 revealed that just over 2000 copies were sold; and just over 600 copies together of The Magical Mimics in Oz and The Shaggy Man of Oz were sold that year. Although O’Donnell continued to write to Snow in 1955 and 1956, Reilly & Lee chose not to pursue any original Oz projects, preferring to see whether redesigning the older titles with new illustrations might stimulate sales.

Early in 1956, Columbia University Libraries mounted a major exhibition of the works of L. Frank Baum. This drew together a sizable number of individuals interested in the Oz and Baum books, including Justin G. Schiller. Snow died on July 13, 1956, some months before the formation of the Club, but Justin Schiller, who founded the Club, has always credited Snow with the inspiration to found the organization. Snow’s lifelong enthusiasm for L. Frank Baum and the Oz books led to his creation of a small, but rich Ozian legacy of two titles in the series and the remarkable Who’s Who in Oz. Beyond that, his encouragement of the young Justin Schiller led to the establishment of a club whose journal continues to support interest in L. Frank Baum and the Oz books more than thirty years later.

A NOTE ON THE SOURCES: The primary sources used in preparing this account of Jack Snow’s writing of Oz books and Who’s Who in Oz are those assembled by Gary Ralph, including typewritten transcripts of letters, many prepared by Fred M. Meyer from the originals, and photocopies of original letters. We must be grateful indeed for the enormous amount of work done by Fred Meyer in assembling and preserving so much of the record of Jack Snow’s life and activities.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.