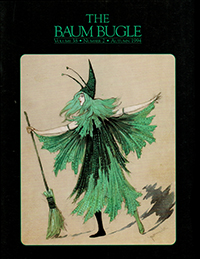

L. FRANK BAUM, THE WITCHES OF OZ, AND THE WITCHES OF FOLKLORE

by Robert B. Luehrs

Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 38, no. 2 (Autumn 1994), pgs. 4–10

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Luehrs, Robert B. “L. Frank Baum, The Witches of Oz, and The Witches of Folklore.” Baum Bugle 38, no. 2 (1994): 4–10.

MLA 9th ed.:

Luehrs, Robert B. “L. Frank Baum, The Witches of Oz, and The Witches of Folklore.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 38, no. 2, 1994, pp. 4–10.

Oz is very rich in the variety and powers of its witches. Dorothy marvels at this fact in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), and so the Good Witch of the North tries to explain why Kansas has nothing comparable. “In civilized countries,” she notes, “I believe there are no witches left; nor wizards, nor sorceresses, nor magicians. But, you see, the Land of Oz has never been civilized, for we are cut off from all the rest of the world. Therefore we still have witches and wizards among us.” (p. 24).

Oz is indeed cut off from the modern world which dull, drab Kansas represents, and so, unlike that world, Oz shares in a venerable and sometimes disquieting cultural heritage that reaches back at least to the neolithic era, a legacy which speaks of witches and their craft. This western tradition concerning witchcraft was transmitted to L. Frank Baum through his general knowledge of fairy tales, legends, and superstitions; through his great interest in the theories of spiritualists; and through his association with the Theosophic movement of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott.[1] Here were major sources of inspiration as he fashioned the witches who fill the Oz stories, and yet his interpretation of this tradition, as might be expected, was frequently quite original. The witches of Oz, as a result, do not always reflect the “historical” images of their kind; they sometimes exhibit most curious qualities.

Witches indulge in magic, so before pursuing further the theme of the relationship between the witches of Oz and the witches of folklore, a definition of magic might be in order. The basic assumption of magic is the existence of hidden relationships among all things. The material and spiritual realms, animate and inanimate objects, the seen and the unseen are all linked by invisible chains of sympathy and mutual influence. Thus a pin thrust into a wax doll harms an enemy, a rabbit’s foot brings good fortune, a horoscope deciphers celestial messages about human destiny, and mistletoe acts both as an antidote for every known poison and as an aphrodisiac. If a witch or other conjurer knows the proper ceremonies, utters the correct incantations, and perhaps calls upon the right gods or demons, that individual will control and command the hidden forces of the cosmos.

Magic, in other words, is viewed by folklore as a sort of occult science, based on “natural” principles which bind the universe together. These principles can be discovered by any individual with the wit and perseverance to secure the knowledge; these principles can then be manipulated to bring about specified results. Such has been the traditional interpretation of magic in the west, and such was the view of the early Theosophists and of Baum. In The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913) the Shaggy Man sings of “Ozland . . . Where magic is a science,” (p. 140) while in Tik-Tok of Oz (1914) he speaks of all nature being magical (p. 161–162). The Adepts in Glinda of Oz (1920) refer to their’ magic as “secret arts we have gleaned from Nature.” Baum’s mother-in-law and fellow Theosophist, Matilda Joslyn Gage, put it this way in her 1893 book Woman, State and Church:

“Magic” whether brought about by the aid of spirits or simply through an understanding of secret natural laws, is of two kinds, “white” and “black,” according as its intent and consequences are evil or good, and in this respect does not differ from the use of the well known laws of nature, which are ever of good or evil character, in the hands of good or evil persons. (p. 236)

The terms white and black magic, which Gage used, are of relatively recent coinage; the more historically accurate distinction is between High Magic and Low Magic, the magic of the wizard and that of the witch. The wizard, the adept of High Magic, is invariably male. He is primarily a philosopher seeking understanding of the universe in order to better himself spiritually and intellectually. Although he may attempt to coerce supernatural beings to serve him, he is more likely to be concerned with natural or Hermetic magic, such as alchemy or astrology.[2] The wizard is feared but respected. He is rarely bothered by the authorities and is often accorded considerable prestige because of his wisdom. The extent to which the Wizard of Oz exemplifies these exalted qualities most assuredly might be debated.

According to the popular view, the practitioner of Low Magic, the witch, is of quite a different sort. The witch is customarily a woman, and her craft is a perversion of the wizard’s art. It is homespun, utilitarian, materialistic, frequently harmful, and most certainly not scholarly. The witch is commonly depicted as a broomstick-riding crone with a propensity for employing dark powers and even darker spirits in working ill on her neighbors. She is anti-social, disagreeable, quarrelsome, bad-tempered, and often physically deformed; the witch, in short, is what most people consider wicked.

This image of the witch took millennia to evolve. Its origins lie in antiquity, where the environment was permeated with magic and otherworldy influences. In the early civilizations the entrepreneurs of magic provided defense against supernatural menaces, dispensed curses, offered cures for disease, purveyed love potions, found lost property, made predictions, and conversed with both gods and ghosts. These were the services of Low Magic. While the ancients deemed such services necessary and generally viewed magic itself as Matilda Gage did, as a neutral power which could be used for either benevolent or malevolent ends depending on the situation, magicians were not really trusted.

Especially suspect were female magicians, the witches. The literature and folklore of the Graeco-Roman world associated witches with night and the netherworld. They were accused of injuring both people and livestock, destroying crops, stirring up storms, provoking lust, hindering love, and being sexually aggressive. They were said to transform people into animals and to assume various shapes themselves. For example, the Roman nightwitch or striga flew after sunset in bird form and preyed on children, devouring their entrails. Witches foretold the future and summoned the dead, forcing them to disclose secrets. There were some exceptions, but for the most part to the ancient Greeks and Romans witches were the opposite of decent women; women were supposed to be caring mothers and respectful wives, not career-minded viragoes with abilities surpassing those of men.

The reputation of women magicians was no better among the ancient Germans. The sagas picture witches as healers but also as alarming creatures who debilitated the enemies of their clients or avenged slights by a magic that involved charms, ceremonies, the manipulation of objects, and spoken or written formulas. At night, according to the legends, they might ride out mounted on flying animals in the company of a motley array of goddesses, souls, and specters; as they careened through the skies they would revel and spread destruction.

The blend of tales from the Mediterranean and from the northern reaches of Europe became the basis for the concept of wicked witches in Medieval and modern times and thus the lore available to Baum as he created his own a self-proclaimed Krumbic Witch with a library of tomes written in blood and a pantry of pickled toads, snails, and lizards.

Baum did, however, reject the most notable and enduring contribution of the Middle Ages to the concept of witchcraft: the idea, propounded by the Church, that a witch secured her power to inflict occult misery through an infamous pact with Satan, whereby he worked mischief through her and she rendered him unwavering loyalty. Witchcraft, theologians argued, was actually devil-worship, and its devotees would periodically gather in secret conclave, in a “sabbat,” to blaspheme Christian rites, give homage to their infernal master, receive instructions about crimes they were to commit, and wallow in unspeakable orgies. Church leaders believed witchcraft to be so dangerous that from the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries they launched major campaigns to exterminate the menace. Inquisitors sentenced hundreds of thousands of supposed witches to death; the majority of the executed were women, who were thought to be easier marks for the Devil’s blandishments than were men.

In harmony with the principles of Theosophy, Baum did not accept the existence of the Devil.[3] Those in Oz who hurt others through magic do so because of flawed personalities and nasty temperaments not because they have sold their souls to the Prince of Lies.[4] Magic in Oz has returned to its ancient roots as knowledge and skill which can be used for all sorts of purposes, good ones as well as bad. Magic in Oz adheres to the definition of magic given by Gage. As a result, Oz has a number of witches who are not wicked at all, something Medieval Christianity would have held to be impossible. Some Oz witches are amoral. The Yookoohoos, Mrs. Yoop the giantess in The Tin Woodman of Oz (1918), and Reera the Red in Glinda of Oz, are neither good nor evil. They are recluses who work magic for their own amusement and are indifferent to whether the results help or hurt anyone else. Both specialize in transformations, an appropriate emphasis, as Brian Attebery has pointed out, for a magical transformation is harmful if altering an identity but beneficial if restoring one.[5] Transformations, in other words, are ambivalent, like the Yookoohoos themselves.

Even more remarkable are the good witches. In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Baum introduced three of them: Gayelette, who used her magic for the advantage of her people and “was never known to hurt anyone who was good;” (p. 172) the Good Witch of the North; and the latter’s glorious, southern colleague, Glinda the Good, the Oz version of a Mother Goddess. Since Ozma is a fairy, she does not belong in the “good witch” category, but the Adepts at Magic in Glinda of Oz do, as does Queen Zixi of Ix. It might be asserted that Queen Zixi of Ix (1905) is not really part of Oz, but she does make a cameo appearance in The Road to Oz (1909), offering some justification for including her in this article. She is a most interesting variation on the good witch: basically benevolent but flawed and quite capable of being driven by wayward emotion to abuse her magical powers.

It is more difficult to find equivalents in folklore for the neutral and good witches of Oz than for the wicked witches but scarcely impossible. The ancient magicians, even the female ones, were not necessarily evil; one’s attitude toward these sorcerers no doubt largely depended on whether one was their customer or their victim. The same was probably true of the village wise women of the Middle Ages. These, Low Magicians were the local physicians, using herbs to heal. They also lifted enchantments, thwarted evil spells, offered protection against calamity, practiced divination, concocted love philtres, conjured spirits, and performed dozens of other supernatural tasks for clients. Even so, the wise women were sometimes blamed when hail ruined a crop or a newborn baby died. In Medieval times even those who did not really buy the Church’s “pact with the Devil” theory of witchcraft retained a definite suspicion that anyone dealing with magic could be treacherous.

The good witches of Oz are very much akin to the wise women as Gage depicted them in her Woman, State and Church. The wise women, she said, were not agents of Satan at all but Medieval disciples of the priestess-scientists who had created the earliest civilization and who had governed it with peace, justice, and morality; when men took over, the character of civilization deteriorated rapidly along with the status of women. The “witches” of the Middle Ages, then, were women with superior intellects and the ability to exercise certain psychic powers unknown to most people. As masters of animal magnetism, a sort of spiritual electricity, the wise women could heal at a touch, defy gravity, and control the weather. Borrowing from the historian Jules Michelet and the folklorist Jakob Grimm, Gage saw the so-called witches’ sabbats as nocturnal protest rallies by the peasantry against an oppressive Church. The sabbats were conducted by the wise women who kept alive, despite fierce persecution, ancient wisdom and pagan religious rites dedicated to the creative power of the feminine, a power the Church wanted to suppress.[6] Gage’s witches essentially practiced High Magic. Baum deeply admired his mother-in-law’s intellectual prowess, once referring to her as “in the first rank amongst the thinkers of our age.”[7] Not surprisingly, he made Oz into the ancient matriarchy reborn where women with supernatural capabilities, whether the four witches in the original Oz book or Ozma and Glinda thereafter, wield the ultimate authority.[8]

Baum modified the ancient and Medieval legends about witches with perceptions derived from his own Theosophical orientation and Gage’s historical theories. The outcome is a fascinating and inventive mix of characteristics. The best way to judge this result is to look at the activities of some of the individual witches—in this case six wicked witches and, more summarily, two of the good witches, Glinda and Zixi.

Of all the Ozian spellweavers, the ones most clearly indebted to the folklore tradition are the Wicked Witch of the West, Blinkie, and Mombi. All three have the requisite appearance and personality. They are very old. Blinkie and Mombi are scrawny, while only Mombi still has both eyes. They are solitary, sadistic, easy to anger, sharp-tongued, tyrannical, and mercenary. Blinkie and Mombi employ strange gestures and noxious brews, and they all conjure with theatrical gestures and incomprehensible incantations, precisely the sort of thing expected of the model witch. Each also reflects individually Baum’s ingenious use of some of the peculiarities associated with the witches of folklore.[9]

The Wicked Witch of the West comes by her fear of water honestly, as water has long been a medium for detecting witches. One of the oldest known legal systems, that of the Babylonian King Hammurabi (1792–1750 B.C.), provided for throwing accused witches into a river; if they sank, they were declared guilty. Christian lawmakers later altered the formula so that those who floated were convicted. The assumption was that the water, having been blessed by a priest beforehand, would reject anyone who was in league with Satan.[10] Another certain mark of a witch was her inability to shed tears, according to the great witch-hunter’s manual, the Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches), published in 1486. Still, no European witch was recorded to have melted in water as does the Wicked Witch of the West. The normal procedure for dispatching witches was to hang them or bum them at the stake, as King Krewl threatens to do to Blinkie.

The wolves, crows, and bees the Wicked Witch of the West summons with her silver whistle might not have been arbitrary choices by Baum. All have connections with the folklore of witchcraft. Human beings have never been comfortable with wolves, those hunters and singers of the night; it was easy to conceive of wolves as agents of witches, unfortunates transformed by witches, or even witches themselves, prowling as ravenous werewolves. Crows and bees were occasionally listed in the annals of witch trials as familiars, lesser demons in animal form who were kept as pets by witches and ran odious errands for their mistresses. In return for services rendered a familiar might be permitted to snack on the witch’s blood, a less than satisfactory exchange in the case of the Wicked Witch of the West; she is so aged that her blood has dried up. Since, according to superstition, a crow or a swarm of bees was a harbinger of death, the Witch is correct to choose these creatures for the mission of destroying Dorothy and her companions. No monkeys were mentioned as familiars by the inquisitors, probably because these animals were not to be encountered in the villages of Europe during the hey-day of the witch hunts. Thus it is quite proper that the winged monkeys, unlike the wolves, crows, and bees, are involuntary slaves of the Wicked Witch of the West, not her willing servants.

While the Wicked Witch of the West primarily seeks through her magic to dominate or destroy others, Blinkie applies her talents in another area of interest to the witches of folklore, the inhibition of love. One of the most popular functions of magic in the Middle Ages was to enflame passion, and the grimoires, the handbooks of Low Magic, were filled with bizarre recipes to this end. Popular opinion supposed that since witches and wise women knew how to kindle love, they could also quell it. Witches were commonly accused of producing sterility in women and impotence in men. There were concoctions for such purposes; one was a heady beverage made of ants boiled in daffodil juice. A favorite method for thwarting any affections between a man and a woman involved ligature, the tying of knots in a cord or strip of leather. Blinkie’s technique of killing Gloria’s love for Pon by dashing a potion on the girl’s breast is rather unorthodox, but Blinkie is thereby fulfilling a role assigned to the genuine witch by tradition.

The three witches who assist Blinkie in mixing her potion are the only ones in Baum’s Oz stories who actually fly on broomsticks. The notion that witches can fly goes back to the Roman strigae and the rampaging nightriders of German mythology. Witches astride airborne brooms were first mentioned in Martin Le Franc’s Le Champion des Dames (The Champion of Women) of 1440 but did not appear in the witch trials until a century and a half later. Before then witches were accused of flying on various means of transportation, including sticks, beanstalks, horses, pitchforks, oxen, goats, dogs, wolves, and beehives. Probably the broom became the preferred aerial steed for witches in peoples’ imagination because it most patently symbolized women. Witches flew, said the experts, to attend distant sabbats. The wicked witches of Oz frequent no sabbats, so they really need no broomsticks.

Mombi’s specialty is transformation. She turns Ozma into Tip and threatens to turn Tip into a marble statue. She changes Jellia Jamb into her own likeness and herself into a rose, a shadow, an ant, and a griffin. Of course, she is not the only Oz witch to deal in shapeshifting. Blinkie metamorphoses Cap’n Bill into a grasshopper. Coo-ee-oh changes Rora Flathead into a Golden Pig and the three Adepts into fish. Through the magic of Mrs. Yoop the Tin Woodman becomes an owl, the Scarecrow a bear, Woot the Wanderer a monkey, and Polychrome a canary; Mrs. Yoop also produces breakfast out of some water, a bunch of weeds, and a few pebbles. The other Yookoohoo, Reera the Red, enjoys altering her own form and those of her pets (or familiars) for amusement. Reera is more skilled than Mrs. Yoop, for the giantess cannot restore what she transforms to its original shape. In The Road to Oz the Good Witch of the North turns ten stones into birds, lambs, and finally dancing girls as party entertainment. Glinda, in Rinkitink in Oz (1916), returns Bilbil the Goat to his original form, the handsome Prince Bobo of Boboland. Still, Glinda does not approve of transformations when they are done maliciously. “. . . they are not honest,” she observes, “and no respectable sorceress likes to make things appear to be what they are not. Only unscrupulous witches use the art . . .”[11]

Glinda’s reference to appearance touches on one of the major controversies about witch-induced transformations. The question was whether such things were real, with men truly becoming animals, or only “glamour,” illusions caused by befuddled and bewitched senses. The ancients argued for reality as did the testimony offered at the witch trials in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The contrary point of view was advanced by St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and other prominent Christian theologians. God, they said, can alter the nature of beings, but witches and demons cannot. At best demons can make men think they have been transformed or that others have been. Since demons are not the source of Ozian magic, presumably the transformations in that land are usually more than glamour. The most obvious exception is Zixi, who appears young and beautiful but is always reminded by mirrors that she is really a bald, toothless, withered hag of 683 years of age.

There is occasion when Mombi does resort to glamour, staged special effects having no substance. Her efforts to impede the advance of Tip and his friends on the Emerald City is such a time. The field of whirling sunflowers, the changing landscape, the rushing river, the wall of granite, the forty crossroads which rotate, and the grass fire are all illusions, surmounted by being ignored. Fraud is to be expected from a witch who studied with the humbug Wizard of Oz.

However, Mombi performs a bit of genuine magic when she glances into a mirror to discern the future. This is scrying, a form of divination in which a seer concentrates on a shiny surface—a crystal ball, a polished stone, a mirror, or even a buffed finger nail—to induce a trance. In that trance the seer gains access to hidden knowledge through visions of past, present, or future events. Glinda similarly looks into a mirror to discover the whereabouts of Button Bright in Glinda of Oz.

Of the other three wicked witches dealt with in this study, Rora, the wife of the Su-dic of the Flatheads, best fits into the conventions of witchcraft. When the Skeezers try to limit the fishing rights of her people, she schemes to poison Skeezer Lake, hoping to kill the Adepts in the process. Poison in the Middle Ages was considered part of the arsenal of any competent witch. Her cupboard was supposed to have an ample supply of lethal liquors and salves compounded from such horrific ingredients as hemlock, hemp, nightshade, human bones, toad glands, and bits of rat. These poisons could be administered orally, rubbed onto victims’ bodies, spread on the ground for the luckless to walk on, or poured into water supplies to wipe out entire populations. So close was the relationship between witchcraft and poison that the passage in Exodus (22:18) which reads “Thou shall not suffer a poisoner to live” is normally given as “Thou shall not suffer a witch to live.”

Rora Flathead operates within the basic traditions of witchcraft, but the Wicked Witch of the East and Coo-ee-oh demonstrate Baum’s willingness to reshape those traditions to suit his own purposes. In the glimpses he offered of the Wicked Witch of the East, she is associated with the Silver Shoes and enchanting an axe to dismember Nick Chopper. Yet, silver and the presumed iron of the axe head are metals which, according to folklore, ward off witches. The silver sixpence in a bride’s shoe, a silver bullet, and a drink containing a silver coin all protect against witches and a variety of other evils. Witches were sometimes charged with enchanting tools, but iron amulets, iron nails in one’s pocket, an iron knife buried under the doorstep, or an iron horseshoe hung on the wall were all supposed to keep iniquitous magic at bay. Obviously such is not the case in Oz; the Wicked Witch of the West even trips Dorothy with an invisible iron bar and grabs one of the Silver Shoes.

Coo-ee-oh does not fit the pattern of the classic witch either. For all her grimoires, powders, and incantations, she is a witch of the Industrial Revolution. Her Krumbic Witchcraft, a kind of occult technology stolen from the Adepts, would have been unimaginable to those living in antiquity or the Middle Ages.[12] Her magic is a means for launching submarines, controlling the cumbersome mechanism that raises and lowers her glass-domed city in the lake, and sending a steel bridge, section by section, from the city to the mainland. This is a unique blend of science and sorcery, with machinery outclassing conjuration.

The Wicked Witch of the East and Coo-ee-oh are both originals, and so is Glinda, who goes far beyond the limitations normally assigned witches. Witches were alleged to have the facility of making themselves invisible, but no legendary witch ever had the capacity to hide an entire country from the eyes of outsiders as Glinda does with Oz. When Glinda flies, she does not perch on a puny broomstick. She often soars through the skies like a pagan goddess in a chariot drawn by storks, the sacred protectors of the home, family, and marital fidelity. Her Magic Recipe 1163 to make inanimate objects move at command combines gadgetry, magical powder, and spellmaking in an elaborate fashion worthy of Coo-ee-oh; Glinda, too, is a witch of the industrial age. Glinda’s most noted possession, the Great Book of Records, is an instant newspaper, complete with editorial comment. Robert R. Pattrick rightly called the Book of Records a tool for divination.[13] It is divination which improves upon Medieval bibliomancy, the opening of a book at random and taking the first passage noticed as prophecy; it is much more sophisticated than the practice of Pope Sylvester II, who supposedly asked questions of a bronze head. The Book of Records is more of a computer than a fairyland marvel.

Glinda herself is a High Magician who employs her knowledge to protect Oz and its inhabitants from harm, to promote the general welfare, and to turn discord into harmony. She is far too selfless to be classified as just a witch. Baum even tried to distinguish her from the other witches by referring to her with some consistency as a Sorceress, although actually the distinction between witchcraft and sorcery is vague. Baum’s point is nevertheless valid; Glinda does not fit the folklore image of the witch.

The same is true of Zixi, easily the most complex of the good witches. Zixi is fundamentally a kindhearted ruler, wise, liberal, just, generous, brave in war and mild in her financial demands on her subjects. However, she can also be deceitful, selfish, and bitter when crossed. She is a sympathetic character because she is capable of intellectual and emotional growth. She learns positive lessons from her mistakes. When the Magic Cloak refuses to grant her petty wish of appearing beautiful in mirrors, she realizes that one must accept one’s lot in life and not yearn for the impossible. Zixi is fine as long as her common sense and reason keep tight rein on her passions. As Baum put it: ” . . . when her mind was in normal condition the witch-queen was very sweet and agreeable in disposition.” (p. 183)

In her role as a witch Zixi brews exotic potions. Her incantations are wonderfully mind-boggling and filled with inscrutable phrases and paradoxes. She speaks the language of the animals and can render herself invisible, both marks of an accomplished witch. Above all, alone among the witches of Oz and its borderlands, Zixi actually does what Medieval and Renaissance witches were executed for: she hobnobs with demons. Twice she consults spirits—”imps” Baum called them. She summons them to weave a duplicate of the Magic Cloak she intends to steal and again to help produce a sleeping draught which would immobilize the Roly-Rogues long enough to rid Noland of their obnoxious presence. These imps, to be certain, are not devils but more like the daimonion (demons) of the ancient Greeks, otherworldly entities which can be most beneficial. Socrates claimed to be guided by a daimon in his search for truth.

Baum may not have believed in the Devil, but he did agree with Theosophy about the existence of a species of daimonion called Elementals. In his newspaper, The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer (April 5, 1890) Baum wrote of Elementals as

. . . invisible and vapory beings . . . They are soulless but immortal; frequently possessed of extraordinary intelligence, and again remarkably stupid. Some are exceedingly well disposed toward mankind, but the majority are maliciously inclined and desirous of influencing us to evil. The legendary “guardian spirit” which each human being has is nothing more or less than an elemental, and happy is he who is influenced thereby for good and not incited to evil.

In this article Baum went on to assert that in a seance the medium is possessed by an Elemental, who is delighted to have an opportunity for conversing with humans and who can relay information from the past but not predict the future. The danger is that the Elemental will not relinquish the host body again.

Baum’s description of the characteristics of Elementals is comparable to that offered by the Theosophist Franz Hartmann in his 1887 book on Paracelsus, the sixteenth-century physician, alchemist, and mage. Baum did amend the Paracelsus-Hartmann definition somewhat by combining their Elementals, nature spirits found in the air, water, earth, and fire, with their idea of the Flagae, unreliable familiar spirits which reveal secrets to man.[14] Furthermore, Blavatsky’s Theosophy calls the spirits who deal with clairvoyants Elementaries, not Elementals. Elementaries are the souls of the dead who lived unworthy lives, while real Elementals were never human. By the time he wrote his children’s stories Baum had moved away from the position that most Elementals are “maliciously inclined.” After all, both Theosophy and Matilda Gage identified Elementals with fairies. The Demon of Electricity in The Master Key (1901) is an Elemental. He observes, with quotations from Hesiod and Shakespeare no less, that his fellow demons were in the beginning good, but “of late years” mortals have chosen to think otherwise. (p. 16–17)

Zixi’s imps are likewise Elementals, and they may be used for whatever ends the summoner desires. Zixi is fortunate, as she calls on her imps and performs her magic, to dwell on the fringes of “uncivilized” Oz. Had she lived in the civilization of the late Middle Ages the Church would have convicted her of trafficking with demons from Hell and consigned her to the stake. In Dorothy’s civilized Kansas Zixi would likely be diagnosed as delusional or psychotic and sent off for treatment or incarceration. In Oz, however, where an imaginative legacy embodying humanity’s oldest hopes and fears intermingles with Baum’s creativity, magic is knowledge—arcane knowledge of the mysterious correspondence among all things in nature but knowledge nonetheless. What is done with this information is the significant point, and that is the basis upon which the witches and wise women of Oz are judged. As it is, the worst that Zixi must endure is a rebuke by Lulea, queen of the fairies, who disapproves of witchcraft in general, but her censure might well be merely professional jealousy.

[1] On Baum and Theosophy see: Michael Patrick Hearn, ed., The Annotated Wizard of Oz (New York, 1973), pp. 69–72 and John Algeo, “A Notable Theosophist: L. Frank Baum,” The American Theosophist, vol. 74, no. 8 (September–October, 1986), pp. 270–273. Baum discussed Theosophy in “The Editor’s Musings” column of his newspaper, The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer on January 25, 1890 (p. 4) and on February 22, 1890 {p. 4). He and his wife joined the Theosophical Society in 1892.

[2] Hermetic magic was named after Hermes Trismegistus (Hermes “Thrice Great”), legendary king of early Egypt, incarnation of the god Thoth, and alleged author of mystical treatises which enjoyed considerable repute in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

[3] See, for example, his column in The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, December 6, 1890, p. 4. There is also a very positive article about a spiritualist who called the Devil a “superstition of the dark ages” in The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, January 10, 1891, p. 5. Baum’s denial of the Devil’s actuality is mentioned by Heam, Annotated Wizard of Oz, pp. 72–73, 102.

[4] The motivations of Ozian miscreants are explored in C. Warren Hollister, “Baum’s Other Villains,” The Baum Bugle, vol. 14, no. 1 (Spring, 1970), pp. 5–11. Baum poked fun at the theory of witches being agents of the Devil in his story “The Witchcraft of Mary-Marie,” Baum’s American Fairy Tales (Indianapolis, 1908), pp. 45–46, 48. (Reprinted in this issue of The Baum Bugle on page 22.) When Mary-Marie asks her witch mentor whether she must sell her soul to Satan in order to learn magic, she is told she should not sell her soul to anyone, and she must use magic “for the benefit of all mankind.”

[5] Brian Attebery, The Fantasy Tradition in American Literature (Bloomington, 1980), pp. 104–107. See also the discussion of Yookoohoos in Roger Sale, Fairy Tales and After: From Snow White to E.B. White (Cambridge and London, 1978), pp. 239–243.

[6] Gage, Woman, State and Church, pp. 217–294. A similar thesis was advanced by the folklorist Charles Leland in Aradia: The Gospel of the Witches (1899); he claimed that the religion of the witches was the worship of the goddess Diana and her daughter, Aradia. Between the two world wars the respected Egyptologist Margaret Murray argued that witches gave homage to a prehistoric fertility god named Dianus. Robert Graves’ The White Goddess (1948) made the witches’ deity female once more, and today’s neopagan witches often dedicate their ceremonies to the Goddess, an embodiment of nature, fertility, and/or the moon.

[7] The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, June 28, 1890, p. 4. Baum also said Gage was the “most remarkable woman of her age, possessed of the highest literary ability, the brightest thoughts, the clearest and most scholarly oratory, the most varied research and intelligence and diversified pen of any public woman of the past twenty years.” The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, March 1, 1890, p. 4.

[8] The Wizard’s government in the Emerald City is based on public relations hype, not on supernatural substance. His great fear is that one of the women with true magic powers will challenge him, for then his fraudulent regime would collapse. The Scarecrow’s administration likewise lacks a sound, magical underpinning and is toppled by women.

[9] Michael Patrick Hearn has pointed out to the author that the similarities between the Wicked Witch of the West and Blinkie may be explained by the fact they are the same witch. Blinkie first appears in the 1915 film His Majesty the Scarecrow of Oz, a version of the first Oz story that was eventually retitled The New Wizard of Oz. Still, in the Oz books Blinkie is separate and distinct from the Wicked Witch of the West and is so treated here.

[10] There is a brief discussion of witches and water in Hearn, Annotated Wizard of Oz, p. 234.

[11] The Marvelous Land of Oz, p. 273. The Wizard of Oz agrees: “It is wicked to transform any living creatures without their consent . . .” (Glinda of Oz, p. 249).

[12] Hugh Poindexter III, “The Magic of Baum,” The Baum Bugle, vol. 21, no. 1 (Spring, 1977), pp. 2–9.

[13] Robert R. Pattrick, Unexplored Territory in Oz {n.p., 1975), p. 21.

[14] Franz Hartmann, The Life and Teachings of Paracelsus (London, 1887), especially pp. 32, 58, 76, 96–102. The concept of Elementals, beings who correspond to the four elements of nature, is at least as old as the ancient Greeks, although the term first appeared in the fifteenth century. Paracelsus provided the earliest detailed account of Elementals, drawing partly on myth and inventing the rest. According to Paracelsus, Hartmann, and Theosophy in general, the Elementals who live in the earth, called Gnomes, are hostile to mankind. The sea and air Elementals, the Nymphs and Sylphs, are benign. The fire Elementals, the Salamanders, tend to have no relationship with humanity. Hearn has pointed out that Baum borrowed these classifications for his fairy tales (Annotated Wizard of Oz, pp. 70–71). The Baum counterparts to the earth, sea, air, and fire Elementals are the Nomes; the mermaids (“sea fairies”); Polychrome and perhaps the mist maidens briefly seen in Glinda of Oz, and the reclusive court of the Great Jinjin, Ti-ti-ti-Hoo-choo in Tik Tok of Oz. According to Abbe de Villars, seventeenth-century author of the occult novel Comte de Gabalis, the ruler of the Salamanders is named Djin. There are similarities between Elementals and the nature spirits in The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.