LOOKING BACK AT A ROYAL HISTORIAN OF OZ

by Michael Gessel

Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 32, no. 2 (Autumn 1988), pgs. 4–5

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Gessel, Michael. “Looking Back at a Royal Historian of Oz.” Baum Bugle 32, no. 2 (1988): 4–5.

MLA 9th ed.:

Gessel, Michael. “Looking Back at a Royal Historian of Oz.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 32, no. 2, 1988, pp. 4–5.

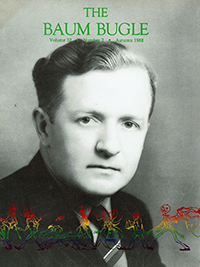

(Note: In print, this article was supplemented with photographs that have not been reproduced here. However, typographical errors have been left in place to accurately reflect the printed version.)

This issue of The Baum Bugle is dedicated to Jack Snow, fourth Royal Historian of Oz. Snow would still be remembered today if he made no other contribution to Oz than writing two Oz books, The Magical Mimics in Oz and The Shaggy Man of Oz. But Snow did much more. His masterwork was not an Oz story at all, but the delightful compilation of Oz lore, Who’s Who in Oz. Though.he never completed his biography of L. Frank Baum, the research he did in the 1940s and 1950s helped later biographers and bibliographers, and it was his suggestion to name a Baum biography To Please a Child. Snow assembled an Oz collection containing some of the rarest and most important Baum material, and used his knowledge to inspire a generation of Oz collectors. Few have ever matched Snow’s enthusiasm for Oz and its creators, and he will never be forgotten for the encouragement he offered other Oz fans to study and enjoy Oz.

We in the Oz Club have a special debt of gratitude toward Snow. Had he lived, he would very likely have been the founder of the International Wizard of Oz Club. In his later years, he proposed establishing an “Oz Irregulars,” somewhat like the Baker Street Irregulars. In a letter to Edward Wagenknecht written one year before he died, Snow wrote:

Just to give you an idea of what amusement could be had by an association of Oz fans: it came to me only a few weeks ago that it was most curious that in The Lost Princess of Oz, Baum should cause Ozma to be transformed into a peach pit. Of course, she was a “peach”—but why the pit? Then it came to me. What was Ozma’s last name in her previous transformation when Old Mombi made her a boy in The Land of Oz?—Tip. Spell Tip backwards!

If it were not for the friendship he formed with Snow, the young Justin Schiller might not have conceived of founding the International Wizard of Oz Club. After Snow died, it was his files that provided the initial Club mailing list. More than half of the charter members who signed up came from among Snow’s correspondents.

Thus, this tribute to Jack Snow is a tribute to the founding spirit of the Oz Club.

Jack Snow* was born August 15, 1907 in a one-story brick house just a few blocks from the center of Piqua, a small Ohio town north of Dayton. His parents were John Alonzo Snow and Roselyn Hyde Snow. While Jack was growing up his father had a variety of jobs as a clothing sales clerk and was briefly the proprietor of a saloon.

*His high school yearbook listed him as John Fred Snow and several obituaries referred to him as John Frederick Snow. However, during his adult life he always went by Jack Snow.

Snow traced his first experiences with literature to the second grade, when he persuaded his mother to buy him a subscription to The Story Tellers Magazine. He developed an intense interest in Oz, and he read everything he could find of L. Frank Baum’s books. When Baum died, Snow even wrote to the Oz book publishers Reilly & Lee offering to take over writing the series.

However his childhood fascination with Oz faded as a teenager, when his attention shifted to radio and writing. While still a high school student, he wrote radio reviews for the Cincinnati Enquirer. He also worked after school at a small shop near the high school which sold locally made radios. He was an avid reader and top student at Piqua High School, but a loner with few friends.

Snow graduated from high school in 1925. His mother died the following year and the family moved to Dayton.

In the next few years, Snow held a variety of jobs in Piqua and Dayton, including working in a drug store, repairing radios, and writing for the Piqua Daily Call. In 1927, he wrote “Night Wings,” the first of a number of his supernatural short stories published in Weird Tales magazine.

In 1929, Snow attended Indiana State Teachers’ College at Terre Haute, Indiana, majoring in English. While a student, he worked part-time as a writer and announcer for radio station WBOW in Terre Haute, and quickly became full-time program director.

After leaving college in 1930, he worked at different times for a number of radio stations, including WSMK of Dayton; WCKY of Covington, Kentucky (near Cincinnati); WOR, WQV, and WAAT of New York; and WJMS of Ironwood, Michigan. He also wrote a program which ran on the NBC Blue Network (the forerunner of ABC).

In 1933, he returned to Dayton and radio station WSMK There he stayed for almost 10 years, eventually becoming continuity editor and publicity director. He wrote announcements, scripts, and copy, and later had his own show, “The Old Reporter,” which ran Monday through Saturdays. Snow was credited with renaming the station WING, calling attention to Dayton’s claim as the birthplace of aviation. Snow was respected as a creative talent as we as an excellent writer and narrator.

One of Snow’s sisters remembered Snow at this time as a quiet, formal man who would never enter a room of company without putting on his jacket. He kept his short frame well dressed, as befitted the son of a clothes salesman. He was surrounded by books in his home, and enjoyed giving books as gifts.

It was in 1940, while still living in Dayton, that Snow was struck by a renewed interest in Oz. He began collecting Baum first editions, and other children’s books. Snow’s enlistment in the Army Air Corps in May 1942 did not detract from his growing interest in Oz. After John R. Neill died in 1943, he again tried to take up the mantle of chronicler of Oz by seeking the support for his case from Baum’s widow, Maude.

About 1943, Snow began researching Baum’s life for a biography. In searching for in-formation, he wrote numerous letters to Baum’s relatives and acquaintances, as well as libraries in places where Baum had lived.

After reaching the rank of sergeant, Snow received a medical discharge from the Army in July 1943. He moved to New York and accepted a position as a writer in the advertising and promotion department of the National Broadcasting Company.

In pursuit of his Oz interest, in 1945 he applied unsuccessfully for a Newberry Library Fellowship in Midwestern Studies to write the Baum biography. However, he did succeed in winning from Reilly & Lee the right to continue the Oz series, resulting in The Magical Mimics in Oz (1946) and The Shaggy Man of Oz (1949). To illustrate these books, he selected Frank Kramer, a New York artist who had done mostly work for sports magazines. Kramer later remarked in a letter that Snow’s “diminutive appearance made him look like one of the Oz characters in the book.”

During this time Snow wrote additional stories for Weird Tales which were collected in an anthology, Dark Music and Other Spectral Tales (1947), which received generally favorable reviews.

Toward the end of the decade, Snow suffered physical and psychological problems. Eventually he lost his job with NBC and sold his collection. He later got a job writing for the Associated Hospital Service of New York (Blue Cross).

In the mid-1950s, Snow tried to get back to writing stories with a submission to Humpty Dumpty magazine, which was rejected. At the request of Fred Dannay, editor of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, he wrote a short story, “Murder in Oz,” which was also rejected. He proposed a new Oz book about Polychrome, entitled Over the Rainbow to Oz. He continued to research the Baum biography, but with little to show for his efforts. Who’s Who in Oz (1954) was his only major work published in the decade, but it sold poorly.

Despite Snow’s medical and financial setbacks, his generosity and warmth remained undiminished. Nor did he lose his sense of humor. Martin Gardner, who met Snow in the mid 1950s while writing an article about Baum for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction recalled that Snow reminded him of an Irish leprechaun.

His last years were lonely ones. One of his friends during this time was young Justin Schiller, who met Snow when he was about 11 years old, and who shared Snow’s enthusiasm for Oz. Years later, Justin remembered Jack sitting on a park bench near his apartment after a visit. It was getting late, and Justin’s parents had to take him back to their Brooklyn home. Snow started·to cry—he didn’t want to go back to his apartment alone.

Snow’s health took a turn for the worse in 1956, and he suffered from dropsy, cirrhosis of the liver, and jaundice. He was hospitalized in July, but after ten days—against his doctor’s advice—he left the hospital. Two days later, on July 13, he died from internal hemorrhaging.

Ethel Cook Eliot, author of The Wind Boy and other children’s stories, had been close to Snow in the 1940s. Though she did not keep in touch with him during his last years, she sent Martin Gardner a long letter upon hearing the news of Snow’s death. In it she wrote:

“Literary ability and imaginative genius—and he certainly had these—are not in themselves, lovable,” she wrote of Snow. “We can admire them—and enjoy the company of people with these high gifts. Jack had these gifts. But he had, over and above them, the gifts of true generosity of spirit, of loving the good for its own sake, and of wanting for others, as he wanted for himself, the reality of love everlasting, and pure.”

Snow is buried in an unmarked plot next to his father in Forest Hill Cemetery, Piqua.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.