Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 64, no. 2 (Autumn 2020), pgs. 5–10

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Crotzer, Sarah K. “Outside Over There: In Praise of Walter Murch’s Return to Oz.” Baum Bugle 64, no. 2 (2020): 5–10.

MLA 9th ed.:

Crotzer, Sarah K. “Outside Over There: In Praise of Walter Murch’s Return to Oz.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 64, no. 2, 2020, pp. 5–10.

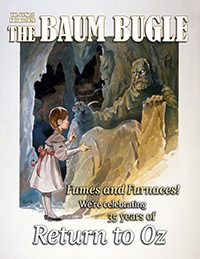

It’s time to stop being ashamed of Return to Oz. No, really. Enough’s enough.

As I prepared this issue, several older friends and acquaintances expressed a certain—well, let’s call it amazement. “But Sarah!” they said. “You can’t possibly love Return to Oz!” I was given various explanations, little outs I could take: surely, I love it because of the Neill aesthetic. Surely, I love it because of its technical innovation. Surely, I love it out of pure, unfettered nostalgia.

Well, that’s true. Nostalgia plays a part in my deep and complex love for the film, just as it plays a part in anybody’s love for a film they enjoyed as a kid. Attributing my entire appreciation for the movie to either nostalgia or scholarly appreciation is only true if we accept the received wisdom: Return to Oz is a bad movie, and anything to like about it is an unintentional byproduct of something that has no inherent value.

I don’t accept that. I spend too much time with movies to make so simplistic a judgment: I’ve been studying them since I was seventeen, when a community college course slammed Citizen Kane and The Third Man straight into my psyche. Twenty years later, I’m the community college instructor pushing classic and modern cinema back on to my students. That doesn’t make me an expert, by any means, but I know something about a filmmaker’s choices and how they are shaped, both internally and externally, to produce a result.

Return to Oz is a great movie. There: I said it. It’s a great movie that does daring, exciting, remarkable things. They’re not the same things as every other Oz adaptation, it’s true, but we’ve taken on all sorts of TV specials, cartoon series, audio adaptations, stage

productions and interpretative pastiche novels that amplify certain aspects of Oz over others. They are all part of the rich, ever-expanding realm of Ozian culture that helps these special little stories continue to stay relevant and attract new fans.

It’s time to let Return to Oz in and give it its rightful place at the table.

Comparisons

A “bad” film is an easy thing to accomplish. All you have to do, as a filmmaker, is be inept. More pointedly, you need your work judged inept by the people paying your salary. The most troubled films come either from filmmakers with unfettered creative control and limited technical skill—Barry Mahon’s The Wonderful Land of Oz (1969) is an obvious candidate—or from executives that exert full control over their product and mutilate the original creative intentions. We’re probably never going to be able to accurately evaluate director Jack Clayton’s version of Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983), a Disney film with much of the same DNA as Return to Oz, because it was reedited, partially reshot, rescored, and apparently bears only partial resemblance to what Clayton (and its writer, Oz fan Ray Bradbury) intended. The entire tone of the piece was changed, and there are scenes where you can see the young protagonists age to adolescence and back again in the space of a single scene: the tell-tale sign

of reshoots. It is, by anyone’s measure, a mediated experience—far more mediated than is entirely comfortable to observe.

Ironically, MGM’s The Wizard of Oz is the perfect example of a film that was put in a blender and set on “pulse.” We’ve known for a long time that there were five directors, and over the years we’ve learned that two of them, at least, had very little to do with what we see on-screen. Everything we know now about the film’s somewhat beleaguered production suggests the movie should not work. Yet, it does; we hold it up, quite rightly, as one of the finest examples of American cinema from the Golden Age of Hollywood.

I would never suggest to you that Return to Oz is an equivalent piece of work, any more than I would suggest to you that an octopus makes a good substitute for an elephant. The two films are doing intensely different things for different reasons. Critiquing Return as a “big studio film” doesn’t recognize the structural difference between the factory model of the 1930s and the independent production companies prevalent in the early ’80s, and it assumes consistent oversight by a studio administrator such as MGM’s Oz producer, Mervyn LeRoy. As director Walter Murch personally attests, however, that didn’t happen. Initially, the studio approved of his work:

We handed [our story treatment] in, it was approved; they liked what we had done. And we took the next step, which was now ‘write a screenplay’, which we did. [ . . . ] There was not a lot of angst about this. They liked what we were doing.1

Then a new administration came in, and their concerns were not over content but budget:

The budget got big . . . and then a crisis emerged because the management of Disney changed, about . . . three or four months before we were supposed to shoot. And the new management didn’t like any of this . . . and they decided to put the film into turnaround, which is to say, “We’re not going to do it, but we will not oppose you if you find somebody else who might take it on, some other studio. But if you, Walter, rewrite the screenplay, so that the budget is significantly reduced, then maybe we will

do it after all.” And that’s a gamble . . . I took the risk, which—on a certain level—paid off.2

It’s telling that Murch’s production problems remained centered on the ballooning budget. At no time does it appear that the studio interfered with the story he wanted to tell. Even when he was briefly fired—“on a Thursday, and by the following Tuesday, I was working again”3—it was entirely related to Murch’s inexperience running such a complex film set, pushing the film’s schedule behind and (inevitably) creating more costs. Even once the film was complete, oversight remained minimal:

A whole new regime took over Disney . . . and they had absolutely no interest in this film because it had not only been started by a previous administration, it was two administrations ago.4

By accident, then, we have the very inverse of the MGM movie: a film that can’t be attributed to a corporatized studio identity but to a single man’s artistic vision. That renders it extremely special within the pantheon of Oz adaptations—in fact, I’ll dare to call it unique. There has never been another interpretation of L. Frank Baum’s Oz books to have the resources of a major Hollywood studio and the guiding principles of a single artistic mind, and it seems unlikely there ever will be again. Why haven’t we all been celebrating that for the last thirty-five years? Why so many backhanded compliments? It’s all about expectations, I think.

Expectations

Recently, I loaned my Return to Oz Bluray to a good friend, born in the 1970s. She watched half of it before pausing for the night. The next day, I asked how it was going. She sighed wistfully, “They’re not ever going to sing, are they?”

Expectations are the single biggest factor in whether an audience judges a film to be “good” or “bad”—completely subjective terms that can serve to devalue any creative decision. Studios that make blockbusters, then and now, place a high currency on meeting the expectations of audiences who want not just as much enjoyment but the same enjoyment they had last time. This has caused the proliferation of popular genres in movies including the Western, the slasher film, the musical, the superhero film, and so on. Yet when we, as audience members, place the same expectations on everything we take in, we intrinsically water down what we allow ourselves to experience artistically.

Return to Oz failed in 1985 because it wasn’t MGM’s Oz. There is no other, grander reason. It isn’t full of vaudeville; there are no big, blousey comic performances; there are few bright colors; and nobody breaks into choreographed dance. Fairuza Balk, a child actor of nine years old, isn’t even attempting the doe-eyed innocence of a classic film ingenue, whether Judy Garland, Lilian Gish, or anyone in between. Crucially, Return to Oz doesn’t offer parents or grandparents any nostalgic blast (unlike Mary Poppins Returns (2018), a Disney sequel carefully and slightly bizarrely constructed to resemble an entirely outdated mode of filmmaking). This is a movie acting entirely on its own terms. I’m not sure how it could have been made otherwise.

What’s interesting to realize is that MGM’s Oz, just like Return to Oz, was seen as something of a curate’s egg by its original audience. It was a modest success in 1939, but it didn’t capture the national mood: the main accolades went to Garland and her personal anthem, “Over the Rainbow.” The movie’s breakaway success came a decade later, after rerelease, most particularly after 1956, when it rapidly started down the path of revered, once-a-year event television. That allowed it to be routinely rediscovered and recontextualized by new generations of children, all of whom consistently failed to have the same expectations from 1939. MGM’s Oz became a movie locked in a sort of time bubble, despite all evidence of its 1939 sensibilities, and it took decades—and a considerable social shift—for kids to start defining it as “old” or “out of date.”

The same thing has happened with Return to Oz, admittedly on a much smaller scale. Those of us growing up in the late ’80s or early ’90s were repeatedly treated to broadcasts on cable’s Disney Channel, and it was one of a relatively sparse selection of live-action Disney movies you could always rent or buy on VHS. In our small sphere, it was as exciting as MGM’s Oz—and often, more accessible for repeat enjoyment. We learned to appreciate it on its own merits, and if you talk to any of us who grew up on it, there’s a distinct reason: we just didn’t have the older folks’ expectations.

My generation often sets the film off from MGM’s Oz by expressing a quality found only in the newer movie. The intense grounding of Murch’s film in everyday details and unshowy compositions makes you feel like you’re actually there, with Dorothy, in the room, experiencing events. Walter Murch’s professional career as an editor is full of this heightened “cinematic realism,” whether it’s the overlapping dialogue of The Conversation (1974), the urban soundscape of The Godfather: Part II (1974), the famous beach assault of Apocalypse Now (1979), or the careful mixture of real and fictional protest footage in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988).

Other writers in this issue comment more thoroughly on Murch’s dedication to the realism of Kansas, 1899, and I agree that, at first, he may not seem like the right person to take on the fantasy world of Oz. Here’s a good experiment you can try: turn off the picture on Return to Oz, or put a big drape over the screen, and listen to the sound. You’ll immediately notice a hundred and one little aural qualities that contribute to the reality of Oz, whether it’s the grind of the Wheelers’ gears, the cracks and snaps of Jack’s twig fingers, the comical “shunk!” of Tik-Tok’s supposedly heavy eyelids, or—as has often been discussed—the whimsical and inventive score by David Shire. Murch uses sound and music to communicate ideas about and smooth over transitions that, in visuals alone, would be extremely hard to sell. It all adds up to a fantastically rich and rewarding, multi-leveled experience, one which MGM’s Oz—a cinematic treasure that is special for entirely separate reasons—cannot replicate.

Yet it isn’t what everyone wanted in 1985. When they got it, audiences were shocked, concerned, and a little bit sad: their expectations had not been met.

Scares

Let’s talk about the other big Gump in the room: just how scared we’re all still supposed to be of Return to Oz, a film released months after Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom ripped the still-beating heart out of a man’s chest.

Admittedly, Spielberg’s Indy adventure led to the creation of the PG-13, but we were already in a PG landscape where a hero got his hand cut off by a blade of super-hot light (The Empire Strikes Back, 1980) and villains’ faces melted off their skulls (Raiders of

the Lost Ark, 1980). Nowadays, we’re almost assumed to be taking any but the smallest children to PG-13 blockbuster fantasy movies where characters are beheaded (The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, 2001), dismembered (The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, 2013), or have their eye gouged out with a pencil for a quick, sick joke (The Dark Knight, 2008). The Walking Dead, a series that routinely raises the “standard” of graphic violence, has been accessible through basic cable for a solid decade.

Return to Oz is still scary? No, I don’t think so.

The film is only scary in comparison to one made forty-five years earlier, and maybe more importantly for us, to stories that are a solid generation older than that. While a general audience would only have been upset by the dissonance between his film and

MGM’s, Murch gave a series of interviews that added insult to injury for die-hard Oz enthusiasts:

It was important to leapfrog over the 1939 film and get back to quintessential Baum . . . I count myelf as a purist and have strong feelings about the OZ books. My major concern is that the essence of “Oz” is well and truly maintained.5

Oversimplistic claims such as this, routinely supported by executive producer Gary Kurtz and producer Paul Maslansky, were only ever going to offend those wanting a book-authentic adaptation. Murch’s Oz is Murch’s Oz, not Baum’s, and it’s a shame they felt the need to try and sell it as anything else.

Baum’s Oz stories are dark, though—considerably dark compared to the expectations we have of young children’s literature today. There are extremely visceral and graphic details in most of his fantasy works: not just the folkloric symbolism of “there were forty crows, and forty times the Scarecrow twisted a neck, until at last all were lying dead beside him”6 but punitive slicing machines that cut people in half; Nomes fed to meat grinders; a decapitated head that doesn’t wish to be reattached; and conversations between friendly characters about being killed by insurgents, being stranded on an island and unable to move forever, and what it would be like to eat each other up. They are full of exactly the kind of content that makes some parents clutch their pearls—while many children turn the page to see what happens next.

The difference is tone. Baum rarely ever lingers on violence or trauma. He usually puts it across with what reads like a twinkle in his eye, a subtle way of making you do a double-take to ask, “Did he just write that?” It feels fatherly—warm, safe, with just a hint of mischief. Here, for instance, is a relatively tame example from The Road to Oz (1909):

“What do you want?” called the shaggy man.

“You!” they yelled, pointing their thin fingers at the group [. . .]

“But what do you want us for?” asked the shaggy man, uneasily.

“Soup!” they all shouted, as if with one voice.

“Goodness me!” said Dorothy, trembling a little; “the Scoodlers must be reg’lar cannibals.”

“Don’t want to be soup,” protested Button-Bright, beginning to cry.

[. . .] Happening just then to feel the Love Magnet in his pocket, [the shaggy man] said to the creatures, with more confidence:

“Don’t you love me?”

“Yes!” they shouted, all together.

“Then you mustn’t harm me, or my friends,” said the shaggy man, firmly.

“We love you in soup!” [. . .]

“How dreadful!” said Dorothy. “This is a time, Shaggy Man, when you get loved too much.”7

The delivery style is old-fashioned, but it’s easy to see the joke and interpret how it would play in a modern stage or film adaptation. There is an explicit threat, but it’s blunted by Baum’s narrative voice, as well as by the act of reading, which allows you to subjectively determine the weight you give the content.

Murch himself sees Baum’s writing in a similar way. In a 2016 interview, with the benefit of space to elaborate, his take on Baum is more subtle:

[Baum] had a definite ability to imagine these rather frightening things, even though he would say . . . “I don’t want to create any heartache in my readers. These books are charming and friendly,” and yes, but—there are things looked at objectively that are strange. And that’s one of the things that attracted me to the books. It was one of the things that, when my mother read these books to me at the age of five or six—I loved this stuff because it made me think in a very interesting way.8

Film is a different medium, though. Because of the inherent nature of the cinema, and Murch’s devotion to a realist aesthetic, all he could do was make the violence even less implicit. Many moments that come from the books—the discovery of the Wheelers, Mombi’s ablutions with her heads, Jack losing his head, the storm at sea—have an unavoidable intensity. Instead of trying to obscure it, Murch leans in and amplifies the effect, resulting in what some saw as a sort of horror movie for kids. What many of the criticisms—and even some compliments—seem to have missed is that Murch modulates that horror with another component.

Humor

In the 1980s and ’90s, humor in kids’ entertainment was very different from what it had been two generations earlier. One writer who dominated the publishing landscape was Roald Dahl, the British author of such extraordinarily popular works as James and the Giant Peach (1961) and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964); today, three decades after his death, his books are never out of print, remaining popular with kids who see what’s funny in the grotesque, the uncomfortable, and the outright violent. Take, for instance, this exchange from Charlie, when the gluttonous Augustus Gloop has been sucked up one of the factory’s pipes:

“He’ll be perfectly safe,” said Mr. Wonka, giggling slightly.

“He’ll be chocolate fudge!” shrieked Mrs. Gloop.

“Never! [ . . . ] I wouldn’t allow it!” cried Mr. Wonka.

“And why not?” shrieked Mrs. Gloop.

“Because the taste would be terrible,” said Mr. Wonka. “Just imagine it! Augustus-flavored chocolate-coated Gloop! No one would buy it.”9

This is certainly not worlds away from Baum, and just as sly in how “seriously” it takes a very grim situation, but it is also significantly more amoral. (Mr. Wonka, the only character who sees the joke, is never quite the villain of the piece.) Return to Oz isn’t humorless, as I have sometimes heard it claimed; however, much of the humor functions in exactly this way. Murch laces the film in sheer camp: Mombi throwing open the doors and melodramatically intoning, “So…!” may be a reference to The Bride

of Frankenstein (1936), but more importantly, it’s so ridiculous in its seriousness that it’s also quite, quite funny—intentionally so, I think. If adults don’t see it, children certainly can; it’s the principle on which many cartoons are built, such as Chuck Jones’ Wile E. Coyote and his endless pursuit of the Roadrunner.

Return to Oz isn’t all “big,” though: the better moments of campery are right at the edges, where first-time viewers may not even notice them. They add a complex aspect to the danger, riding the line right between what’s horrific and what’s funny, just as in the Baum texts.10 Some are purely visual—the beautifully achieved stage effect of Mombi’s cabinets of heads, each judging and silently commenting on the action with their eyes—while a few more may even be improvised. One of my favorite moments in the entire film comes when the Nome King reveals his ruby slippers to Dorothy, an inherently ridiculous moment by anyone’s measure. At the end of his line, “Go home…?”, the Nome King prissily turns in his toes, momentarily a little girl himself. Is he mocking Dorothy, or—wrapped up in his negative self-image—is he just thrilled to make her jealous over “his” pretty shoes? The mind boggles in delight at the thought.

The scary aspects of Return to Oz, then, are not as scary as they may initially seem. They may even be a convenient scapegoat to evade a deeper, far more central tenet to Murch’s vision, one that is entirely absent from Baum but meaningful to the fantasy culture of 1985.

Terror

Most of the big “dark fantasy” films enjoyed by children of the 1980s are about terror—the kind of childhood terror Hollywood would never have been willing to acknowledge in the 1930s. The NeverEnding Story (1984), nominally about a kid standing up to

some bullies, is suffused in existential dread created by parental loss; the “villain,” an insentient dark force called “the Nothing,” spreads like entropy and consumes everything in its path. Labyrinth (1986) is about the edge of adolescent female sexuality; The Witches (1990) explicitly says that too-friendly strangers want to kidnap and eat you. The already-mentioned Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) is about the stark gap between a young boy and his elderly father, neither of whom know how to

reach each other, and an entity willing to exploit that divide. Finally, of course, there’s Return to Oz (1985)—no longer so outrageous in context.

These films have a few things in common. First, they are all based on popular written works by highly respected authors; they have, in a word, credibility.11 More pertinently, they all failed at the United States box office. Why?

I would suggest it’s because they all work aggressively against a tradition in American children’s entertainment to say that everything will be okay. The issues they bring up—adolescent changes, death of a parent, death of the self—are, by their very nature, not

okay. Having faced such issues, children can never go back to ignorance, and some of childhood is gone. These films acknowledge fears every child has glimpsed, momentarily, and been unable to put their finger on—not the fear of a scary monster but fear of something deeper. In fact, they intentionally work against the cotton-candy platitudes of earlier movies like MGM’s The Wizard of Oz, which ends:

. . . If I ever go looking for my heart’s desire again, I won’t look any further than my own backyard. Because if isn’t there, I never lost it to begin with!12

What does that mean? Folksy wisdom like this had some relevance in the culture of 1939, when children grew up, married, worked, and died in the same community, but it was already old-fashioned and naïve by the end of the 1960s for anyone but the extremely privileged. Kids who grew up in the 1980s and ’90s were consumed by incitements toward upward mobility and unending cable news cycles that scared us with the Gulf War and Polly Klaas.

Murch himself has managed to identify why his film concerns parents so much:

Aunt Em in particular, because she’s a mother figure, takes Dorothy to a place which might ultimately do her harm: this clinic. [She] leaves Dorothy there to go back to deal with her husband, Henry, and we know . . . that something funny is going on here. Halfway down the road she should say, “Hmm, there’s something funny about this place. I’m going to go back and take Dorothy out of there.’ But she doesn’t. [. . .]

So the scary sub-basement of the sub-basement of the story is: grownups can hurt you, potentially, while trying to help you. [ . . . ] This is the message that I overtly wanted to put into the film, to make kids realize that in some circumstances—sometimes in life you’re on your own and even the people who are there to protect you [can’t]. Things go funny sometimes, so you have to be on alert.

And this is fundamentally a very challenging idea for the kids, and . . . for the grownups who might be sitting next to the kids, who may not want the kids to get this message.13

That’s a startling admission. It reinforces why comparing the two visions of Oz—1939 and 1985—is never going to be satisfactory. Whether you agree with its implications, the entire point of MGM’s movie is for Dorothy—and the child watching—to learn

that she is always loved and valued. In Return to Oz, all the love in the world doesn’t matter. Your parents, one day, will leave you. Your friends may care about you, but they will leave, too. You have to learn to rely on yourself, in the end. That’s a pretty important message, and a mature one, too—but it isn’t very comforting, and it isn’t very light.

If you talk to kids from my generation, movies like these made us feel resilient. We came back to them again and again not just because they entertained us but because they spoke to us very deeply, about something we couldn’t articulate. We wouldn’t

have the right words for years, but the emotions were already there: unfiltered, unsentimentalized, and truthful.

To this day, there are many movies I watch because they offer pure escape: a beautiful, cinematic fantasy where outrageous, impossible worlds and eras are painted in Technicolor hues. The ’80s fantasy films are not like that. Return to Oz isn’t like that. When I watch them, I can see myself in them, looking back.

Joy

In his contemporary review of Return to Oz, subtitled “The Joy That Got Away,” former Baum Bugle editor John Fricke found much to compliment in the film’s special effects, its realization of Ozian creatures, and the performances of several cast members, all areas that I agree are particularly fine. His suggestion that “the viewer is called upon to supply his own joy, his own knowledge of Oz and Dorothy at their peaks” is probably true, too.14 I don’t think I see that as being as detrimental as John does, though; to a significant degree, I think it’s (again) part of Murch’s vision to delay our satisfaction. What few criticisms I have, though, are reserved for the film’s resolution in the Emerald City: a little too quick, a little too simple, with less impact than it should have in an Emerald City that isn’t very emerald. If nothing else, it would have been nice to see the sun come up, a simple visual demonstration of Baum’s American frontier philosophy that there will always be a new day.

That moment of swelling warmth isn’t quite there. Yet I have never found it a cold film, and I have never heard it described by anyone who grew up with it as a cold film, either. The joy is not in that resolution, nor in the quest: the joy is in the details, or more specifically, in the commitment Murch and his team made to their world. Jack, Billina, Tik- Tok, and the Gump—the crew went to impossible lengths to present them as physically realistic characters, speaking in recognizable dialogue, imbued with a humanity you should not be able to give inanimate objects. They have verisimilitude, and delightfully, that doesn’t change with time: I can look at them today and believe in them as I did when I was a child, and I can show them to a child who believes in them, too.

They’re right there, alive in the movie.

I can believe in Dorothy, too, so perfectly brought to life by Fairuza Balk. She may not be Baum’s Dorothy, but they have a lot in common, including determination, pragmatism, empathy, and fortitude. This is a Dorothy I want to know: one who can lead an army to the abyss at the top of the mountain, one who doesn’t lose heart when she’s all on her own, and one who finds her ultimate happiness playing with her little dog. Balk’s naturalistic performance carries me through it all, right to the end.

I hope, this fall, everyone will give Return to Oz another look, whether on Disney+, DVD, Blu-ray, or your ancient, off-air VHS. Is it perfect? No—but if you haven’t seen it in a while, it’s a better movie than you think, and if you like it already, it’s as good as you remember. It’s a full-throated adventure in Walter Murch’s Oz; not, perhaps, the one you expected, but we’ve been waiting for you to join us on the ride, all the same.

Keep flying straight, Mr. Gump. Keep flying until dawn. Soon we’ll find you a safe place to land.

1 Walter Murch, “Writing the screenplay for Return to Oz,” interview by Christopher Sykes, Web of Stories, April 2016, uploaded March 29, 2017, https://www.webofstories.com/play/walter.murch/120.

2 Walter Murch, “Looking for Kansas in England,” interview by Christopher Sykes, Web of Stories, April 2016, uploaded March 29, 2017, https://www.webofstories.com/play/walter.murch/121.

3 Walter Murch, “Fired on Thursday, rehired on Tuesday,” interview by Christopher Sykes, Web of Stories, April 2016, uploaded March 29, 2017, https://www.webofstories.com/play/walter.murch/122.

4 Walter Murch, “Three different administrations at Disney Studios,” interview by Christopher Sykes, Web of Stories, April 2016, uploaded March 29, 2017, https://www.webofstories.com/play/walter.murch/126.

5 Walter Murch, in “Return to Oz,” by Alan Jones, Cinefantastique 15, no. 1 (July 1985): 27.

6 L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Chicago: Geo. M. Hill, 1900), 143.

7 L. Frank Baum, The Road to Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Britton, 1909), 108–10.

8 Walter Murch, “Why Return to Oz seems scary,” interview by Christopher Sykes, Web of Stories, April 2016, uploaded March 29, 2017, https://www.webofstories.com/play/walter.murch/127.

9 Roald Dahl, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1973). Revised edition. Originally published 1964. 81–82.

10 I observed this same tendency of Baum’s writing in “The Rescue of the Tin Woodman,” Baum Bugle 62, no. 3 (Winter 2018). Then, I wrote about the Tin Woodman’s discovery of his original head, quite alive but somewhat grumpy, in The Tin Woodman of Oz (1918).

11 The NeverEnding Story is adapted from the first half of Michael Ende’s novel, first published in Germany in 1979. Something Wicked This Way Comes was adapted by Ray Bradbury from his own work, published in 1962. Return to Oz, as most readers will know, is primarily an adaptation of Baum’s Ozma of Oz (1907) with some characters and ideas from The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904). The outlier is Labyrinth, which is largely the invention of Jim Henson and his screenwriters. Its central conceit, however—a girl whose baby sibling is spirited away by goblins—is taken, with acknowledgement, from Maurice Sendak’s picture book Outside Over There (1981). That work’s title, and its expression of a journey to unknown territory, has also inspired the present article.

12 Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, and Edgar Allan Woolf, The Wizard of Oz (New York: Smithmark, 1993), 156.

13 Walter Murch, “The underlying message in Return to Oz,” interview by Christopher Sykes, Web of Stories, April 2016, uploaded March 29, 2017, https://www.webofstories.com/play/walter.murch/128.

14 John Fricke, “Return to Oz: The Joy That Got Away,” Baum Bugle 29, no. 2 (Autumn 1985): 11.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2024 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.