It all began with a children’s novel published by an obscure Chicago outfit at the dawn of a new century. Well before the days of international media conglomerates and technologically accelerated word-of-mouth, the Oz books were the Harry Potter series of their time. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), published by the George M. Hill Company, was an instant hit, becoming the bestselling children’s book of the year. The New York Times deemed it “ingeniously woven out of commonplace material…. The story has humor and here and there stray bits of philosophy that will be a moving power on the child mind and will furnish fields of study and investigation for the future students and professors of psychology…. [I]t will indeed be strange if there be a normal child who will not enjoy the story.” Baum’s text and the fanciful illustrations of W. W. Denslow both received universal praise. The rest is history; The Wizard of Oz has never been out of print and has sold untold millions of copies.

It all began with a children’s novel published by an obscure Chicago outfit at the dawn of a new century. Well before the days of international media conglomerates and technologically accelerated word-of-mouth, the Oz books were the Harry Potter series of their time. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), published by the George M. Hill Company, was an instant hit, becoming the bestselling children’s book of the year. The New York Times deemed it “ingeniously woven out of commonplace material…. The story has humor and here and there stray bits of philosophy that will be a moving power on the child mind and will furnish fields of study and investigation for the future students and professors of psychology…. [I]t will indeed be strange if there be a normal child who will not enjoy the story.” Baum’s text and the fanciful illustrations of W. W. Denslow both received universal praise. The rest is history; The Wizard of Oz has never been out of print and has sold untold millions of copies.

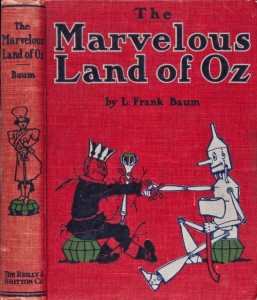

Baum returned to Oz in 1904 with The Marvelous Land of Oz. Baum and Denslow had parted ways due to creative differences, and the new novel was illustrated by the young artist John R. Neill. It was the first book put out by the new firm of Reilly & Britton, which had formed for the express purpose of publishing the first sequel to The Wizard of Oz. As delighted as children were to read more about the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, they bemoaned the absence of Dorothy, whom Baum brought back in Ozma of Oz (1907), one of the most popular books in the series. The Wizard reappeared in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz (1908), and The Road to Oz (1909) included Toto’s long-awaited return. But Baum had begun to feel creatively confined by the expectation of an annual Oz book, and tried to finish the series with The Emerald City of Oz (1910), which ended with Dorothy, Aunt Em, Uncle Henry, and Toto living happily in fairyland.

Baum returned to Oz in 1904 with The Marvelous Land of Oz. Baum and Denslow had parted ways due to creative differences, and the new novel was illustrated by the young artist John R. Neill. It was the first book put out by the new firm of Reilly & Britton, which had formed for the express purpose of publishing the first sequel to The Wizard of Oz. As delighted as children were to read more about the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, they bemoaned the absence of Dorothy, whom Baum brought back in Ozma of Oz (1907), one of the most popular books in the series. The Wizard reappeared in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz (1908), and The Road to Oz (1909) included Toto’s long-awaited return. But Baum had begun to feel creatively confined by the expectation of an annual Oz book, and tried to finish the series with The Emerald City of Oz (1910), which ended with Dorothy, Aunt Em, Uncle Henry, and Toto living happily in fairyland.

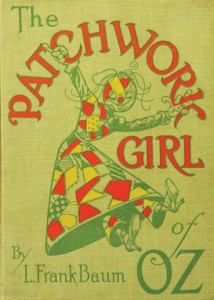

As intent as Baum was on telling new kinds of stories, however, he had underestimated the determination of his child readers. When his next two fantasy novels, The Sea Fairies (1911) and Sky Island (1912), yielded underwhelming sales, Baum saw the writing on the wall. He returned to Oz in a big way in 1913 with not only a new full-length novel, The Patchwork Girl of Oz—a great fan favorite to this day—but also a set of six short Little Wizard Stories of Oz to introduce Dorothy and her friends to younger readers.

As intent as Baum was on telling new kinds of stories, however, he had underestimated the determination of his child readers. When his next two fantasy novels, The Sea Fairies (1911) and Sky Island (1912), yielded underwhelming sales, Baum saw the writing on the wall. He returned to Oz in a big way in 1913 with not only a new full-length novel, The Patchwork Girl of Oz—a great fan favorite to this day—but also a set of six short Little Wizard Stories of Oz to introduce Dorothy and her friends to younger readers.

While Baum continued to write series books for both boys and girls under a number of pseudonyms, Sky Island was his last attempt to write a fantasy novel about anything except Oz. By the time of his death, he had written 14 full-length Oz novels, the last two of which, The Magic of Oz (1919) and Glinda of Oz (1920), were published posthumously.

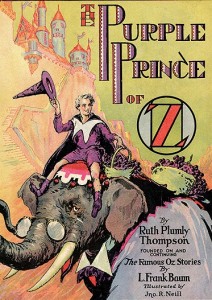

Baum’s publishers, who had changed their name to Reilly & Lee in 1919, were unwilling to let the series die with him. With the approval of Baum’s widow, Maud, they engaged a talented young Philadelphia writer, Ruth Plumly Thompson, to continue the Oz books. Thompson’s writing style was markedly different from Baum’s. Her tone was often more whimsical than his, and she enjoyed introducing elements of international culture—the Far East, the Middle East, Europe—to Baum’s distinctively American milieu. But the second Royal Historian won many loyal followers, and the Oz books continued to appear regularly even during the lean Depression years. Thompson wrote a book a year from 1921 to 1939, adding 19 titles to the series before growing weary of the annual task.

The third Royal Historian was also the second Royal Illustrator. John R. Neill, who had expertly decorated every Oz book except the first one, wrote and illustrated three stories of his own between 1940 and 1942. Neill was much more of an artist than a writer, and his death in 1943 provided an organic pause for the long series of Oz books, whose ongoing publication was further complicated by the materials shortages World War II had caused.

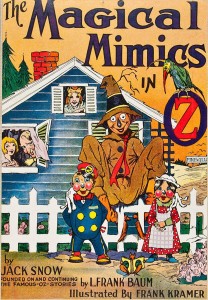

By now the series had existed for more than 40 years, enough time for a lifelong Oz fan to seek the Royal Historian mantle. Jack Snow had first written to Reilly & Lee at age 12, shortly after Baum’s death, to offer his services. A quarter-century later, the polite “no” he had received as a child turned into a “yes.” The Magical Mimics in Oz (1946) and The Shaggy Man of Oz (1949) were conscious attempts to recapture the flavor of Baum’s writing; Snow disliked Thompson’s books and ignored the characters and situations she had invented. Reilly & Lee hoped for a successful rejuvenation of the series, but Snow’s two titles, illustrated by New York artist Frank Kramer, suffered from lackluster sales. Snow went on to write Who’s Who in Oz (1954), a lavishly produced biographical encyclopedia of Oz characters; that book, too, failed to find a wide audience. He died in 1956, but not before befriending a young Oz fan named Justin Schiller. With the help of Snow’s correspondence files, Schiller contacted other Oz enthusiasts and formed the Wizard of Oz Fan Club, soon to be redubbed the International Wizard of Oz Club, in the months after Snow’s death.

By now the series had existed for more than 40 years, enough time for a lifelong Oz fan to seek the Royal Historian mantle. Jack Snow had first written to Reilly & Lee at age 12, shortly after Baum’s death, to offer his services. A quarter-century later, the polite “no” he had received as a child turned into a “yes.” The Magical Mimics in Oz (1946) and The Shaggy Man of Oz (1949) were conscious attempts to recapture the flavor of Baum’s writing; Snow disliked Thompson’s books and ignored the characters and situations she had invented. Reilly & Lee hoped for a successful rejuvenation of the series, but Snow’s two titles, illustrated by New York artist Frank Kramer, suffered from lackluster sales. Snow went on to write Who’s Who in Oz (1954), a lavishly produced biographical encyclopedia of Oz characters; that book, too, failed to find a wide audience. He died in 1956, but not before befriending a young Oz fan named Justin Schiller. With the help of Snow’s correspondence files, Schiller contacted other Oz enthusiasts and formed the Wizard of Oz Fan Club, soon to be redubbed the International Wizard of Oz Club, in the months after Snow’s death.

Meanwhile, only one new Oz novel was published in the 1950s. Another longtime Oz fan, Rachel R. Cosgrove, submitted an unsolicited manuscript to Reilly & Lee. The result was The Hidden Valley of Oz (1951), illustrated by Michigan artist Richard “Dirk” Gringhuis. Cosgrove sent the publisher another Oz manuscript, which they declined. It finally appeared in print decades later when the International Wizard of Oz Club published The Wicked Witch of Oz (1993), with illustrations by Eric Shanower.

By this point in its history, Reilly & Lee’s fortunes had declined, and it was sold to Henry Regnery in 1959. Regnery made an attempt to revive interest in the moribund Oz series, and when accomplished children’s author Eloise Jarvis McGraw and her daughter, Lauren, expressed interest in collaborating on a new Oz book, the firm accepted their offer. Merry Go Round in Oz (1963), illustrated by Oz Club member Dick Martin, would be the last book—number 40—in the official series.

By this point in its history, Reilly & Lee’s fortunes had declined, and it was sold to Henry Regnery in 1959. Regnery made an attempt to revive interest in the moribund Oz series, and when accomplished children’s author Eloise Jarvis McGraw and her daughter, Lauren, expressed interest in collaborating on a new Oz book, the firm accepted their offer. Merry Go Round in Oz (1963), illustrated by Oz Club member Dick Martin, would be the last book—number 40—in the official series.

But the conclusion of the “Famous 40,” as the original books have been dubbed, was far from the end of a stream of new Oz books. The Wizard of Oz had entered the public domain in 1956, and its sequels eventually followed suit. Dozens of writers have published their own continuations of the Oz series, now hundreds of titles strong. The loose ends, contradictions, and indelible characters and situations created by seven different Royal Historians have proven too tempting for other writers not to explore in their own works. Ruth Plumly Thompson herself returned to the Oz series with two new titles, Yankee in Oz (1972) and The Enchanted Island of Oz (1976), both published by the Oz Club. The Club also published The Forbidden Fountain of Oz (1980), a new story by the McGraws, as well as The Ozmapolitan of Oz (1986) by Dick Martin, the illustrator of their first Oz book.

Long before the meteoric rise of print-on-demand, Oz buffs were writing a dizzying array of new sequels. Today, with the ease of self-publishing, Oz books continue to proliferate, giving fans fresh works to enjoy. The saga begun by L. Frank Baum well over a century ago continues.