PRINCE OF POP-UPS

(Part of “Three Faces of Oz”)

by Jane Albright

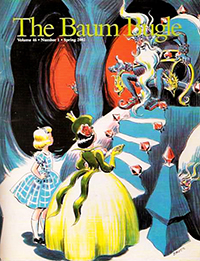

Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 46, no. 1 (Spring 2002), pgs. 21–24

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Albright, Jane. “Prince of Pop-Ups.” Baum Bugle 46, no. 1 (2002): 21–24.

MLA 9th ed.:

Albright, Jane. “Prince of Pop-Ups.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 46, no. 1, 2002, pp. 21–24.

(Note: In print, this article was supplemented with photographs that have not been reproduced here.)

For the centennial of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), artist and paper engineer Robert Sabuda created a new edition of the classic story: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: A Commemorative Pop-Up. If my five-year-old is any indication, it’s an edition sure to please the children of today. Each page presents a sequence of spectacular pop-ups filled with color and largely faithful to W. W. Denslow’s original illustrations.

Robert Sabuda’s first real venture into the world took him from his childhood home in rural Michigan to art school in New York City. For him, leaving his town of 800 to plunge into life at Pratt Institute was an experience comparable to Dorothy’s arrival in the Emerald City. Today he’s traveled the world and makes New York City his home, but at thirty-six he hasn’t lost the ability to marvel with a child’s eye. And he’s taught himself to create in ways that spark that sense of wide-eyed wonder in an innocent heart. As a writer and illustrator of children’s picture books, Sabuda, with unparalleled use of animation and dimension, brings stories to life.

“As a poor kid growing up, my best books—my only hardbacks—were pop-up books from the Hallmark series,” he says. “They told stories, taught me things, took me places. One flew me to the moon!”

His early appreciation for pop-ups led him to create his own first pop-up at age eight. It, too, was The Wizard of Oz. “My mom was a secretary,” he remembers. “Long before you could buy card stock—when there weren’t office supply stores on every corner—she’d bring home these large used manila envelopes from old mail that were going to be thrown. They were just the right size and weight, and already had a fold. Perfect for my pop-ups. I made my first Wizard of Oz with them.”

Unfortunately, that black and white copy didn’t survive to share shelf space with its spectacular 2000 sequel. In the ensuing years, Sabuda has become meticulous about archiving his work. “I lost the blank dummy of my first major pop-up book, The Christmas Alphabet. It was one of those panicked moments to realize I couldn’t find it. Now I keep everything.” Labeled, indexed, and stored in archival boxes, his illustrations and preliminary pop-ups for Oz are carefully preserved.

Blank pop-ups were the first tasks in the two-year development of Oz. “Paper and scissors are where you start with paper mechanicals,” he explains. “It’s pointless to draw and hope. You just begin to make them, repeatedly changing, taping, fixing, improving, to make sure the pop-up action works. And not just once, but over and over again. Then you can add details that don’t affect the mechanics, like the doors and windows cut in the Emerald City.” He particularly struggled to design the Wizard’s hot-air balloon to his satisfaction. “I wanted it to really expand and show some movement,” he says. “The balloon leaving without Dorothy is one of the emotional moments in the story. Dorothy’s missing that balloon was pivotal. So I wanted it to be just right.”

Only after the mechanical wonders of paper, string, dowels, and glue all work does illustration begin. “And sometimes I’ll still go back and make changes. There has to be five millimeters between any two pop-up pieces that are going to be cut out from the printed sheet; it’s a production issue. I submit that layout with all the illustrations fitting together. And I spend all kinds of time trying to get every bit of paper I can out of that sheet of paper—that one more tiny illustration worked in—to add just a little bit more in the book.”

Oz included nearly three hundred cutouts that Sabuda illustrated front and back. In an admirable effort to be faithful to Denslow’s work and to the production methods of 1900, Sabuda first drew every illustration for his book by hand and picked a color palette for printing each color that would appear on its pages. “I think if something’s not broken, you don’t fix it. The integrity of the original illustrations is important to me. The Wicked Witch of the West had to have that eye patch, that umbrella. There had to be green glasses.” He then transferred his line drawings to linoleum blocks that he carved into printing blocks. The inks were applied to those blocks, which were then used to print the illustrations.

Denslow’s work didn’t include any large images of the Emerald City itself, so Sabuda had some freedom to work. “Until I came to New York as an adult, I’d never been in a building more than five stories tall. I’d never been in a museum. I knew how Dorothy would feel seeing the Emerald City, and I wanted some feel of that in the Emerald City pop-up. And when I see a pop-up, the child in me wants to go inside it and look around. To satisfy that curiosity in me, I have to illustrate the backs of everything. To add little extra touches kids would have fun with.” The green spectacles he included for viewing the Emerald City pages prompted a note from the publisher. Sabuda had made a mistake, they wrote; the glasses were sized for adults and should be made just to fit kids, since no adult would ever wear them. Sabuda knew better and held his ground. Photos he shot at the production plant in South America show that even the plant manager was seen sporting green Sabuda specs. “Although the only time you’ll see any secret messages through them is when you’re in the Emerald City,” he adds.

He brought the same respect to Baum’s text. “Who could tell this story better than Baum? I edited down the text myself to make it work with this kind of book. I wanted to retain what I considered the most important emotional connections that I’d felt reading it as a boy. But I didn’t change anything. I see no reason to change or apologize for the way Baum and his characters expressed themselves. If a child asks why they speak like that, you explain that that’s the way people spoke one hundred years ago.” That retelling factor is, in his view, the biggest drawback of other published pop-up versions of Oz. “Retelling makes it a picture book. I wanted to create a pop-up book of the real story. All I wanted to add was three-dimension.”

Though not an Oz collector, Sabuda is an avid collector of rare books that feature paper and other mechanicals. His particularly prized items include male and female anatomy textbooks that prepare the modest reader for undue shock with discreetly placed overlays. One turn-of-the-century title, The Speaking Picture Book, has tiny paper bellows attached to knobs that make a distinctive sound when turned. He has contemporary pop-ups, too, including many earlier versions of The Wizard of Oz. His research has led him to discover books as far back as 1536 that used various moveable devices to teach astronomy and other topics. Children’s stories began to include paper features around 1805; simple flaps lifted to reveal hidden illustrations.

The public enthusiasm he sees now for pop-up titles is a professional high for Sabuda. “I love hearing people say they’ve ‘never seen anything like that’ about a pop-up,” he says. “After thirteen years of producing books, it’s wonderful to see people appreciate paper as a moving art form like they never have before. They get excited about these books and want to share them, so they’re giving them to kids.” Children’s reactions to his books are an especial treat. Asked if there were any particularly vivid memories of his whirl-wind Oz promotion tour, he didn’t hesitate. “The Reading Reptile here in Kansas City staged a production of The Wizard of Oz with a cast of kids. Right in the middle of all those back-to-back appearances, it was so fun to see kids just enjoying Oz.”

During his own grade-school years, Sabuda enjoyed Oz in much the same way. “The Oz books I read were [Del Rey] paperbacks from the public library. The Scarecrow was my favorite character. In fourth grade I rewrote my own version for a school play, making his part bigger than Dorothy’s! The whole thing began in that cornfield. Naturally I cast myself in his part. I was so proud of that production. I remember think-ing all the people and parts were just fabulous, top-notch. I thought the costumes, sets, poppies, and Yellow Brick Road were near-Broadway in their production quality. Then recently on a book signing back home, my fourth-grade teacher showed up with photos from it. I had to laugh. It was really so bad! There I am in torn jeans and a hat. Only one memory was true: all our faces were just beaming.”

The assembly process of Sabuda’s pop-ups takes place at a production facility in South America. Sabuda’s pattern for laying out all the pop-up pieces is digitized and fed into a laser cutter that burns matching grooves into a wood block. Craftsmen then bend razor-sharp metal pieces to follow the lines. These are tempered and placed into the grooves, creating, in effect, a giant cookie-cutter that will stamp the pieces out of the printed sheet. Workers then spend about two months armed with the cutout pop-up pieces and glue, putting each book together by hand. With Oz, Sabuda was an on-site overseer, armed with a camera; his shots of the production serve to reinforce the unique value of his book. Images show row after row of workers sitting shoulder to shoulder, producing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Had he known sooner what it takes to produce pop-up books of this quality, Sabuda says he would have approached his earlier titles differently. “I don’t take ‘no’ for an answer very easily,” he says. “In much of my earlier work I didn’t realize what I could have done if I’d just been more determined. Now I’ve created a monster and am booked for the next two years with projects. The Wizard of Oz was one I wanted to do; I called my publisher, proposed it, and got the go-ahead. They let me do it my way.”

You can learn more about Robert Sabuda on his Web site, www.RobertSabuda.com.

A Note to Bibliographers

The first edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: A Commemorative Pop-Up, with a press run of about 250,000 copies, was imprinted with “first edition” on the back cover. Subsequent printings have been made, and foreign translations are currently being produced. Due to a distribution error, no fewer than three collector’s editions were created. The first of these, distributed by the publisher, had the book cased in fabric and included an additional pop-up. Books of Wonder then offered a more exclusive edition that included a print-an original piece of artwork-Sabuda created for that version, and presented the book in a slipcase. The publisher inadvertently included those copies, however, with its own collector’s edition. Sabuda then provided another set of the prints, using a different color envelope to hold the original artwork for distribution through Books of Wonder.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.