Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 63, no. 3 (Winter 2019), pgs. 7–16

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Wise, Dennis Wilson. “PYRZQXGL: or, How to Do Things with Magic Words.” Baum Bugle 63, no. 3 (2019): 7–16.

MLA 9th ed.:

Wise, Dennis Wilson. “PYRZQXGL: or, How to Do Things with Magic Words.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 63, no. 3, 2019, pp. 7–16.

Words have power—and, as far as clichés go, this is an obvious one to start an article on magic words. My subtitle riffs on J. L. Austin’s classic How to Do Things with Words, in which he argues that words can function as “performative utterances” that go beyond merely describing the world to actually changing or shaping it as well. For example, take the phrase “I do.” If spoken during a wedding, that phrase can change one’s life (and hopefully for the better), but the specific context grants “I do” a binding legal and social power that disappears if spoken in a different context. Performative utterances like this appear everywhere in everyday language. Unfortunately, the performative utterances specifically discussed by Austin are hardly magical; they provoke little sense of awe, mystery, or mystic arcana.

A more interesting category of performative utterances are curse words. In his Encyclopedia of Swearing, the sociolinguistic Geoffrey Hughes catalogues a social history for profanity, oaths, foul language, and slurs, and he explains that “‘sacral’ notions of word

magic” govern all acts of swearing—the “belief that words have the power to change the world.”1 For Hughes, swearing can range anywhere from swearing on a Bible to swearing at another driver who cuts you off . Yet even an entertaining performative utterance such as profanity only affects our social world, not our natural or physical world. Only the most storied performative utterances of all time—that is, magic words—have that power.

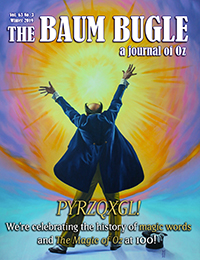

In honor of the 100th anniversary of The Magic of Oz, I’d like to spend some time on PYRZQXGL, perhaps the most memorable aspect of L. Frank Baum’s thirteenth Oz book. While Baum probably invented PYRZQXGL out of thin air, magic words nevertheless

have a long—if not necessarily a sordid—history. All magic words are performative utterances; they refer to the “belief that words, especially when used ritualistically or in some form of incantation, have the power to unlock mysterious powers in nature.”2 Since they harken back to some of our oldest ideas on how language operates, Baum would have found many examples from which to draw inspiration.

Yet any closer examination of PYRZQXGL requires that we separate two things: what the word does from how the word does it. In Magic, Kiki Aru’s magic word produces transformation—and transformation, as a literary concept, has been around for well over thirty centuries. The mechanism or “how” of PYRZQXGL, on the other hand, obviously centers on a single magic word. Although Oz has many transformative magics, this particular mechanism—a word that bypasses supplemental incantations, magical items, or hand gestures—is entirely unique, even as far as magic words go.

My final section takes a peek at magic words after Baum. Generally, they appear only in fantasy written for children, which arguably makes sense. “Every magician,” observes one contemporary stage practitioner, “knows that even young children are deeply moved by magic words.”3 Yet, although most adult readers seem to have become desensitized to abracadabra-type magical systems, there do exist a few adult fantasies that attempt to breathe fresh life into this tried-and-true theme. They extend the tradition into waters uncharted by Oz’s original Royal Historian.

PYRZQXGL: What it Does

PYRZQXGL, obviously, is a word of transformation, and the art of transformation—especially evil transformation—inundates Oz. Yet not all Ozite transformations are created equal, and Baum complicates his magical terminology with happy-go-lucky inconsistency. His most sustained attempt to demarcate between different magical branches comes in Glinda of Oz, but, for all Baum’s scientific pragmatism, the details remain vague. Although Ozma explains to Dorothy that she is “not as

powerful as Glinda the Sorceress” and has different abilities from Glinda, the Wizard, and other fairies, Baum seeks mostly to avoid a single all-powerful figure rather than to construct a rigorous prototype for science fantasy4—a subgenre that would develop, actually, a few decades later through pulp magazines like Unknown and Other Worlds. Baum does explain how Ozma’s magic derives from nature rather than learning, which is how Glinda and the Wizard acquire their powers, but even that explanation provides few concrete details—there are no distinctions, for example, between sorcery, thaumaturgy, wizardry, geomancy, illusion, telekinesis, telepathy, or even necromancy. Baum himself sometimes calls Glinda a witch and other times a sorceress. In either case, how Glinda’s powers differ from a wizard’s or a magician’s remains an open question.

Still, despite Baum’s handwaviness, we can hazard some magical distinctions using traditional terminology. Alongside transformation, thaumaturgy ranks right up there as a frequent Baumian go-to. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, thaumaturgy is simply the “working of wonders” or, more simply, “miracle-working.” It is engineering by other means—through it, practitioners can accomplish wondrous yet useful feats. The best thaumaturgists are Glinda and the Wizard. For the Wizard, magic is basic trial-and-error helped along by educated guessing. It’s like “unlocking a door,” he says, where “all you need is to find the right key.”5 Likewise, when Glinda has to confront the problem of raising Skeezer Island in Baum’s final Oz book, she begins experimenting on a small model. Yet the truest thaumaturgist may be Coo-ee-oh from Glinda. She combines magic with machinery to an unparalleled extent; magic syllables replace electricity or fossil fuels as an animating power. She even gloats that she has “‘magic powers greater than any fairy possesses,’” indicating a hubristic faith in technology over nature that Coo-ee-oh’s fellow thaumaturgists, Glinda and the Wizard, have the wisdom to avoid.6

Plenty of lesser magical forms also appear throughout the Oz books. In The Tin Woodman of Oz, Mrs. Yoop the Yookoohoo (who herself has great transformative ability) possesses telepathic mind-reading powers. Another art form is alchemy. Although

The Patchwork Girl of Oz dubs Dr. Pipt a magician, both the Powder of Life and the Liquid of Petrifaction are clear-cut alchemical concoctions. Indeed, the Liquid of Petrifaction even utilizes the infamous alchemical principle of transmutation, or changing of one substance into another.7 In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Dorothy’s silver shoes enable instant teleportation. Other magic is simply locomotive. For instance, Glinda’s magic recipe No. 1163 makes inanimate objects move at her command.8 Conjuration, too, plays a decent-sized role. In Glinda, Ozma conjures tents out of nothingness for herself and Dorothy; in contrast, when the party needs tents in Emerald City, the Wizard requires the old mainstay of transformation, transfiguring those tents out of handkerchiefs.

This return to transformation leads back to the question of why transformation might have played such a key role in Baum’s imagination— outside plot convenience, of course. If we look at children’s literature during the latter half of the 19th-century, we

can probably rule out any American influences. As Levy and Mendlesohn note in their wonderful Children’s Fantasy Literature: An Introduction, American children’s literature prior to Baum—despite some excursions into the fantastic by Washington Irving, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville—had a “very real antipathy to the fantastic.”9 Fantasy was better employed by British children’s literature, and one might recall Alice’s transformations in size in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in

Wonderland. Baum clearly derived some inspiration here. When visiting Bunnybury in Emerald City, Dorothy must be shrunk down to rabbit-size (by a white rabbit, no less) in order to gain admittance to the town.

The theme of transformation, nevertheless, goes much deeper and further than 19th-century children’s literature. The ancient Greeks loved transformation in particular. Niobe turns into a stone; Daphne spends time as a laurel tree; Io lives life as

a cow; and so forth. In The Odyssey, the enchantress Circe famously turns Odysseus’ men into swine via a magic wand; Odysseus only avoids the same fate thanks to the herb moly. The god Zeus himself especially had trouble staying in one shape. When he wasn’t tricking other gods into changing into flies (as he did to Metis the Titan), he was transforming himself into various people and critters so that he could be alone with some new—and temporary—girlfriend.10 As such, any writer

dedicated to using Greek myths would naturally include many transformations. One good example is Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote two children’s books, A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys (1852) and Tanglewood Tales (1853), that retold classical myths. One story, included, for example, the legend of King Midas, whose touch transformed anything into gold. Yet in strictly literary terms the quick one-stop-shop for all transformation stories would be the

epic Latin poem Metamorphoses, written by the Roman poet Ovid. The opening lines of his poem succinctly state his thesis:

My mind leads me to speak now of forms changed into new bodies.11

Ovid borrowed his material mainly from the Greeks, which explains why his epic poem has a Greek title.12 Metamorphoses is a virtual cornucopia of transformations—humans into inanimate objects, humans into constellations, humans into animals, men into

women (and vice versa), and even some rather pedestrian changes in color. Today, particularly since the Renaissance, Ovid’s works have fallen out of favor. Like a bad children’s author, Ovid never pretended to believe in the stories he told, and so his work often seems superficial and condescending. Still, it would be hard to over-emphasize his immense contribution to Western literature. Shakespeare, Dante, Chaucer, Boccaccio, Spenser, and Milton, all admired Metamorphoses, happily re-working its content

into their own new stories. Baum’s education might have overlooked one of two of these All-Time Greats—but not all of them.

At a basic level, Baum would have grown up reading stories, one way or another, which factored in transformation; so have we, for that matter. Yet because of this pervasiveness Baum had a lot of tradition with which to work—even if more than a few of his

fictional transformations were spur-of-the-moment inventions.

PYRZQXGL: The How (or the Mechanism) of the Magic

The primary agent by which transformation occurs in The Magic of Oz is by saying PYRZQXGL. This word, however, is simply the easiest Baumian method of transformation. Mrs. Yoop has the second easiest method: she merely points a finger at something. Her fellow Yookoohoo, Reera the Red, requires a special powder directed by a stated word. Otherwise, transformation usually requires a complex combination of magic tools, handwaving, and cantrips. The Nome King initially needs a Magic Belt for his transformations in Ozma of Oz, but his post-Belt career requires a spell, which Baum gives us as

“Adi, edi, idi, odi, udi oo-i-oo!

Idu, ido, idi, ide, ida, woo!”13

This spell is noteworthy, not only for its ascending and descending vowels, but also for being a near perfect palindrome. Historically, the perceived link between magic and language meant that magicians have liked experimenting with the alphabet, not unlike how mathematicians play with numbers and number sets to create intriguing patterns. Similarly, the Wizard uses a cantrip—a short rhymed couplet, in fact—to effect his own transformations: “Tents of canvas, white as snow, / Let me see how fast you grow!”14 Rhyming sets of words and minor cantrips appear quite often throughout Baum’s books.

Such spells might not seem drastically complicated in and of themselves, but PYRZQXGL allows even a talentless idjit like Kiki Aru to employ potentially empire-creating magic with little to no practice. Simply pronounce the word correctly; then, poof.15 Kiki Aru’s companion, the former Nome King Ruggedo, even comments on the wonderful simplicity of Kiki Aru’s method. “When I was king of the Nomes,” he says, “I had a magic way of working transformations that I thought was good, but it could not compare with your secret word. I had to have certain tools and make passes and say a lot of mystic words before I could transform anybody.”16 Ruggedo’s old method also came equipped with limitations—his Magic Belt could be stolen, for example.

Yet magic words have quite the long and fascinating history, even apart from the issue of transformation. If I had to guess, the most immediate precursor on PYRZQXGL might be Richard Burton’s famous edition of The Arabian Nights (1885; the first widely successful American edition appeared in 1903). In the story of Ali Baba and the forty thieves, Ali Baba opens a cave filled with fabulous treasures by the simple expedient of saying, “Open, sesame!” Opening or locking doors, indeed, has long been a province of magical words. The Lord of the Rings even has one: outside the West-door of the Mines of Moria, an inscription in Elvish reads “Say ‘Friend’ and enter.” The wizard Gandalf only has to say mellon, the Elvish word for friend, for the door to open.17

Still, fiding direct influences on Baum’s employment of a magic word hardly seems necessary. Like the idea of transformation, the idea of magic words can be found everywhere. With all due apologies to alakazam and voilà, the most popular magic word of all

time is probably abracadabra. No one quite knows the proper etymology but, according to the OED, it’s been around since at least the 4th century AD. Today, the word has become meaningless through overuse, incapable of evoking the awe and mystery proper to a magic word, but many writers, ancient and modern alike, still try to keep it alive by quirky reformulations—for example avada kedavra, the Killing Curse, in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books. (Simply try pronouncing both words out loud.) Also of note is the Swedish equivalent to abracadabra, sim sala bim. Although this word was popularized by “Dante the Magician” (aka Harry August Jansen) long after Baum’s death, it deserves honorable mention for appearing in Sam Raimi’s Oz the Great and Powerful (2013).

Still, the odd magic word does appear in a few children’s books contemporary to Baum, although none with PYRZQXGL’s amazing simplicity. Julian Hawthorne (son of Nathaniel) once wrote a story called “Calladon” in which a young boy—Calladon—lives

in a house of three concentric circles named Abracadabra. The story contains more allegory than fantasy, however, and “Abracadabra” is a name rather than something magical. More relevant is Frank R. Stockton’s Ting-a-Ling (1870). This tale briefly refers to a queen of the fairies who speaks a magic word, yet we never learn the word itself, nor does it function without a magic wand. The closest 19th-century equivalent to PYRZQXGL that I could find, in fact, is probably eternity in the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale “The Snow Queen” (1844). Yet even eternity is no perfect match. A commonplace word like this has greater symbolic than mystic value; while it carries a certain evocative mystique, much like Paris or freedom, it nonetheless fails as a true stand-alone magic word.

Indeed, we should probably distinguish true magic words from two other closely related (but distinct) literary phenomena: nonsense literature and true names. For my money, a true magic word must (a) be a word or short phrase; (b) exclude simple grammatical diction like prepositions, articles, and conjunctions; (c) be neither a proper name nor a commonplace word; and (d) have a magical effect on the world. Words like PYRZQXGL, open sesame, and abracadabra fulfill all these criteria. I’m excluding the Wizard’s cantrip cited earlier, though, because it contains dull grammatical diction, and I’m also excluding—somewhat arbitrarily, I admit—Roquat’s magical near-palindrome because it lacks the same powerful brevity of my paradigm magic words; we might better call it a magic spell.

What about nonsense literature, which creates a host of strange and evocative words? Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky” might have been the most famous example known to Baum, but quality nonsense verse had some well-known American practitioners, too. A fair amount was written by Laura E. Richards, who incidentally also wrote an animal fantasy starring a little boy named Toto, and who created the word “eletelephony.” Nonetheless, I think we can safely exclude the numerous inventions from nonsense literature. Although these words—bryllg, toves, elephop, telephong—lack any literal or esoteric meaning, which is good, they have no direct magical effect on the world. Also, such words tend to a cutesy-ness that forestalls any emotive power or mystical resonance, one of the reasons why commonplace words have been disbarred in the first place.

True names, however, are a powerful form of word-magic, and I’ve excluded them only to make our discussion of PYRZQXGL more manageable. According to Claude Lecouteux in his Dictionary of Ancient Magic Words and Spells, the power of naming infiltrates

much folklore, myth, culture, and literature, and he links true names to the notion of numen est nomen—i.e., “a spirit’s power is embedded in its name.”18 In folklore, obviously, we have the case of Rumpelstiltskin, but many other cases exist as well. In the folklore of Northern England, for example, it was said that giving a name to a boggart would render them uncontrollable and destructive. Likewise, Jewish tradition holds that a golem will come to life if you write its name on paper and slip it under its tongue. The power of names goes even further back in history. In the Book of Exodus, when Moses asks God to name Himself, God evades the question by answering, “I am that I am”—thereby denying Moses any power over Him. Moving forward a few millennia, a young Bilbo Baggins does something similar in The Hobbit. When Smaug asks Bilbo his name when under the Lonely Mountain, Bilbo instead answers with such titles as “Ringwinner,” “Luckwearer,” and “Barrel-rider.”19 Such evasion is a good idea for practical as well as esoteric reasons, as we learn later in The Fellowship of the Ring. Gandalf admonishes Bilbo for foolishly giving his true name to Gollum, who eventually relays it to Sauron, enabling the Dark Lord to seek Bilbo out in the Shire.

PYRZQXGL, though, has a character quite different from either true names or nonsense verse; hence, it seems a true magic word. We might wonder, though, as to its effectiveness as a magic word. PYRZQXGL clearly has the power of transformation, but why might Baum choose that particular collection of letters as opposed to some other collection? Unpronounceability is the most obvious reason, of course, but the aural force of a magic word doesn’t usually depend on its strangeness or tongue-twisting uniqueness. In fact, magic words tend to be part of some divine, adamic, or empowered language—in the case of the Golem, for example, name-magic works only because of the inherent divinity of Hebrew. But Baum, characteristically enough, gives no etymology or explanation for PYRZQXGL. That leaves us room to speculate on other properties the word may have had for him.

My main hunch is that Baum wanted something not only unique and unpronounceable but also phonetically non-frightening. And PYRZQXGL, curiously, evades all the recommendations Craig Conley offers in Magic Words: A Dictionary to modern stage magicians for pronouncing magic words. According to Conley, the effectiveness of a magic word comes from the showmanship of its pronunciation. Conley’s first two recommendations are:

(1) Respect Consequences

(2) Cultivate Reverence

Kiki Aru clearly treats PYRZQXGL without reverence, nor does he fear the consequences of the powerful magic he invokes. Stage magicians in modern times engage their audiences through the suggestion that they are delving into esoteric realms of dangerous magic (however illusionary the danger may be). Kiki Aru, however, speaks PYRZQXGL with the same mystique as one would say “hopscotch”; as a result, Baum avoids making Kiki Aru’s magic too terrifying for his young audience. Even more interesting, though, is how PYRZQXGL out-Germans the Germans in pure consonant-laden madness. The phonetic distribution of Baum’s word makes following Craig Conley’s next two recommendations impossible:

(3) Elongate vowels

(4) Savor syllables

Medieval historian Claude Lecouteux effectively seconds these criteria by noting how charms usually work “through the melody and the prosody of the language”; clearly, something like PYRZQXGL has neither melody nor prosody. One cannot elongate vowels in a word without them and, since all English syllables require vowels, whether orthographically represented or not, PYRZQXGL technically has no syllables to savor.20 Indeed, we might even contrast PYRZQXGL with a vowel-happy magic word like aeeiouo that Craig Conley attributes to the “Greek-Egyptian magical papyri dating back to the second century BCE.”21 These papyri were repositories of arcane knowledge and mystical secrets containing spells, recipes, formulae and prayers, interspersed with magic words and formulas often written in shorthand; long strings of vowels were said to invoke great power.22 Although PYRZQXGL clearly has great power in The Magic of Oz, its lack of vowels simultaneously undercuts any magical feel. It prevents PYRZQXGL from resonating with history’s other great-voweled magic words: abracadabra, sim sala bim, alakazam, voilà, abraxas, and so forth. Again, although I doubt whether Baum knew this long history, I nevertheless suspect he naturally intuited how PYRZQXGL would comically undermine the terrifying mystique invoked by other, more famous magic words.

Still, as ludicrous as PYRZQXGL might seem, it avoids the elevated baby talk to which subsequent children’s fantasy writers would often turn for their own invented words. Indeed, magic words have hardly stopped with Baum. With a few exceptions, though, they tend to appear in fantasy geared toward younger audiences.

Magic Words in Fantasy: Literature After L. Frank Baum

In a literature that works at odds with the purely scientific worldview, fantasy novels after Baum have surprisingly tended to avoid magical words. Fantasists often invent new words and new names, even new languages, but magic words are a rarer beast—as if fantasy authors, seeking out astounding and ever more wondrous systems of magic, deliberately wish to subvert the traditional linkage between magic and logos (the Greek term for word or reason; e.g., “In the Beginning was the Word” [logos]). The Abhorsen books by Garth Nix, for example, use a system of magic based on the sounds made by different bells. Brandon Sanderson uses a metal-based magical system in his Mistborn trilogy, and Brent Weeks has a light-based system in The Black Prism. Likewise, tapping or exploiting a reservoir of magical power is standard fare in non-verbal magical systems. Exemplars include the Wheel of Time series by Robert Jordan, the Myth books by Robert L. Aspirin, the various Valdemar books by Mercedes Lackey, plus many more.

Sometimes authors break the link between magic and logos by the simple expedient of leaving the mechanics of their systems unexplained. To take a recent popular example, George R. R. Martin ties magic to dragons in The Song of Ice and Fire without worrying too much about mechanics. Yet the grandmaster of all fantasy fiction authors, J. R. R. Tolkien, perhaps tops the list in unexplained magical systems. Readers know that Gandalf ’s wizardry is somehow tied to his staff but know few other specifics. Indeed, the Lady Galadriel even professes not to know what Sam Gamgee means by “magic”—a point that emphasizes the ignorance of Faramir, noble as he may be, when he later refers to Galadriel as the “Mistress of Magic who dwells in the Golden Wood.”23

Still, the intuition linking magic and logos is strong enough that many authors maintain it, albeit often in understated ways. Far and away, true names are the most common form of magic words. Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogy, Patrick Rothfuss’s Kingkiller Chronicles, and Glen Cook’s Black Company series all grant true names power over people or objects. An intriguingly complicated case comes courtesy of Stephen R. Donaldson’s three Chronicles of Thomas Covenant. On one hand, his Seven Words of Power—Melenkurion abatha! Duroc minas mill harad khabaal!—fulfill all the basic criteria of genuine magic words: unusual, powerful, lacking in grammatical diction, and none of them a proper noun. In the Last Chronicles, furthermore, we learn these words are part of “the language of the Earth’s making and substance rather than of the Earth’s peoples,” implying a divine or original language, a key traditional explanation for magical power.24 On the other hand, these allegedly magical words are clearly Donaldson’s attempt to mimic the effects of invoking “Elbereth” in The Lord of the Rings, a true name—both inflict unexplained pain on evil beings without, in truth, producing any observable magic.25

Otherwise, genuine magic words have little place in non-comic fantasy written for adults. Part of the reason has to do with the desire for magical systems of greater complexity, which offers better plot opportunities; another reason probably concerns the fear that readers will scoff at some glorified version of abracadabra, since such words have been thoroughly co-opted by modern-day stage magicians and illusionists. A few modern authors of epic fantasy, though, have attempted to take magic words seriously. The most well-known example comes from David Eddings, who founds his magical system in The Belgariad and The Mallorean on the Will and the Word—focus one’s will, say the word, and a sorcerer can change his surrounding physical world. Unfortunately, the word muttered by sorcerers is never a magic word. The hero Garion specifically asks Mister Wolf if the word spoken must be magic, but Wolf provides a deflating answer—such things belong only to charlatans.26 Instead, the best usage of genuine magic words in adult epic fantasy comes from the A Man of His Word series by Dave Duncan. Although we are never given a full magic word in its entirely, people can “collect” a maximum of four, and the acquisition of each new word bestows a higher set of powers. Duncan earns a lot of mileage from this simple system, working out the social and political ramifications in fascinating detail, and he provides the best comparison to Baum’s PYRZQXGL within the adult epic fantasy corpus.27

Far and away, though, the most common post-Baum magic words come from children’s and Young Adult literature; Baum’s The Magic of Oz sets the tone for quite an impressive list of books and authors. As a general rule, the younger the intended audience, the sillier or more sing-song-y the words. Good examples include gargle giggle fiddle num dee in John Burningham’s Cloudland (1999), arzemy barzemy yangelo igg lom in T. A. Barron’s The Merlin Effect (1994), and shazza bowzer googly nowzer in Susan Meddaugh’s Lulu’s Hat (2002). Likewise, blue lightning sparks erupt in Tony Abbott’s Search for the Dragon Ship (2000) after a child character utters nomee-akweepetree. Although such magical words and phrases forego any dangerous mystique in the same way as PYRZQXGL, they also have a nursery-rhyme quality unpossessed by Baum’s original. A young adult fantasy series often credited with employing magic words seriously is Le Guin’s aforementioned Earthsea trilogy—although, as stated, her words are actually true names rather than magic words. For example, the word tolk is simply the name for “rock” in True Speech.28

The honor of greatest inventor of magic words in children’s literature, though, goes to J. K. Rowling. We’ve already mentioned reworking abracadabra into the Killing Curse, but her seven Harry Potter books also contain a host of other evocative, powerful, and Latin-based magical words: accio, legilimens, imperio, incendio, aparecium, reducio, relashio, and many more. Although the Harry Potter books eventually cross the line from children’s literature to young adult literature, growing progressively darker in tone, Rowling has a brilliant comic flair, and her magic words strike a fine balance between the ridiculous and the serious. Yet even her magical system misses on the simplicity and practicality of PYRZQXGL in Baum. Spells like accio and imperio can’t work by themselves. They require innate magical talent and a magical item, usually a wand attuned to a specific user. As such, Rowling’s wizards can suffer the same pitfalls as Baum’s Nome King—if someone steals the wand, or if it gets broken, so much for the wizard’s power.

At the end of the day, PYRZQXGL does seem to be unique—not only in terms of unpronounceability but also in its complete independence from magical items. Rarely, furthermore, has any magic word played as central a role in the plot as PYRZQXGL. Children’s fantasy literature has been the most open to following in Baum’s footsteps, although adult epic fantasy has experimented with some heavily modified or understated variations on the core concept as well. Ultimately, The Magic of Oz is the result of a long history of transformations within Western culture, and while writers after Baum may not have used his book as a direct inspiration for their own magical words (when they use such words at all, that is) Baum’s thirteenth Oz novel was nonetheless among the first American fantasy texts to reinvigorate, however whimsically, an ancient tradition linking magic with logos.

1 Geoffrey Hughes, introduction to An Encyclopedia of Swearing: The Social History of Oaths, Profanity, Foul Language, and Ethnic Slurs in the English-speaking World (New York: Routledge, 2006), xvi.

2 Hughes, An Encyclopedia of Swearing, s.v. “word magic.”

3 Craig Conley, Magic Words: A Dictionary (Newburyport, MA: Weiser, 2008), 27.

4 L. Frank Baum, Glinda of Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Lee, 1920), 58.

5 L. Frank Baum, The Magic of Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Lee, 1919), 211.

7 The Liquid of Petrifaction transmutes anything, including wood, into marble, which makes it perhaps the most unintentionally brilliant invention of all time. Alchemy’s traditional Holy Grail, the transmutation of lead into gold, is useless in a place like Oz. Not

only is gold already the land’s most common metal, Oz has no currency or monetary economy. Actually, Baum’s Liquid reminds me of a scene in David Eddings’s Mallorean series. An alchemist named Senji notes that a colleague, attempting to transmute lead into gold, instead accidentally transmutes glass into steel. This failure so disillusions his colleague that he “burned all his notes and joined a monastery.” This story appalls Eddings’s two roguish sorcerers, Belgarath and Beldin, and the latter complains, “Glass is just about the cheapest stuff in the world—it’s only melted sand, after all—and you can mold it into any shape you want. That particular process might just have been worth more than all the goldin the world.” David Eddings, The Sorceress ofDarshiva (New York: Del Rey, 1990), 138.

9 Michael Levy and Farah Mendlesohn, Children’s Fantasy Literature: An Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 49.

10 Zeus’s unions usually resulted in children. Intriguingly, Hindu mythology has a somewhat similar story. One Hindu creation myth explains the diversity of life on earth by two gods who kept transforming into different beasts and procreating while in those forms.

11 Ovid, Metamorphoses: A Norton Critical Edition (New York: Norton, 2004), 15.

12 “Metamorphosis” means the same as “transformation” or “transfiguration,” but the latter two words come from Latin.

13 L. Frank Baum, Tik-Tok of Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Britton, 1914), 191.

14 L. Frank Baum, The Emerald City of Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Britton, 1910), 152.

15 Incidentally, the best pronunciation of PYRQXGL I’ve seen comes courtesy of Quora forum user Sandhya Ramesh, who recommends “peer-zah-cox-gol” or “purze-kwix-gull.” (I’ve also seen “peer-zuh-kex-gul” suggested.) A commenter on the Quora post,

Philip Newton, recommends a “Polono-Maltese” combination—pronounce the first half in Polish, the second half in Maltese, and you get the counterintuitive two-syllable pronunciation of “pish-ishgle.” These wildly varying suggestions, incidentally, lead to a

fascinating question: what transcription system, exactly, did Kiki Aru’s father use when writing down the proper pronunciation of the word? The most common method today is phonetic transcription, which visually represents speech sounds written in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Each English sound has its own symbol, usually given in square brackets after the word—for example, see the word Oz [ɑːz]. Even phonetic transcription, though, can be divided into alphabetic, iconic, or analphabetic, leaving us to wonder, “Was Bini Aru a great linguist, or the greatest linguist?” Sandhya Ramesh and Philip Newton, “Re: How Would You Pronounce Pyrzqxgl?,” Quora, February 14, 2014, https://www.quora.com/How-would-you-pronounce-Pyrzqxgl.

17 J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (London: HarperCollins, 1994), 300.

18 Claude Lecouteux, preambulus to Dictionary of Ancient Magic Words and Spells: From Abraxas to Zoar (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015).

19 J. R. R. Tolkien, The Annotated Hobbit: Revised and Expanded Edition (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002), 279.

20 Granted, some magic or powerful words have been orthographically represented without vowels, such as the famous Tetragrammaton, YHWH. Even today the Arabic language leaves out vowels in written language. Baum, however, provides no indication that PYRZQXGL follows such a model.

21 Conley, Magic Words, s.v. “aeeiou.”

22 Conley, Magic Words, s.v. “aeeiou.”

23 Tolkien, Lord of the Rings, 652.

24 Stephen R. Donaldson, The Runes of the Earth (New York: Berkley, 2007), 220.

25 In Tolkien’s mythology, Elbereth is the Sindarin (Elvish) name for Varda the Vala, who first outlined the stars in the heavens for the awakening Elves. For Tolkien, a devout Catholic, invoking “Elbereth” in the presence of evil has the same power as speaking a

saint’s name or invoking Mother Mary. Like Donaldson, Paul Edwin Zimmer is another secularized example of this tendency. In his Dark Border books, invoking Hastur in the presence of the Night Things confers pain.

26 David Eddings, The Pawn of Prophecy

27 Still, adult epic fantasy has a number of honorable mentions. In The Truth (2000), Terry Pratchett parodies the whole notion of a magic word—in this case, fazammm—by having a group of bored trainee conjurers recite their magical catechism by rote. Likewise, Jack Vance employs magic words such as tzip and tzap in his picaresque sword-and-sorcery Dying Earth novels. In a non-comic vein, Blake Charlton’s strikingly original Spellwright trilogy, while not employing magic words per se, nonetheless grants spoken words a physical dimension—a major problem, indeed, for Charlton’s dyslexic protagonist. A host of shared-world fantasy novels, such as Forgotten Realms or Dungeons and Dragons, also seem relatively open to magic words, perhaps thanks to their association with tabletop gaming.

28 Ursula K. Le Guin, A Wizard of Earthsea (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2012), 50.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2024 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.