THE LOST COMIC BOOK OF OZ

by Michael Gessel

Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 31, no. 3 (Winter 1987), pgs. 6–8

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Gessel, Michael. “The Lost Comic Book of Oz.” Baum Bugle 31, no. 3 (1987): 6–8.

MLA 9th ed.:

Gessel, Michael. “The Lost Comic Book of Oz.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 31, no. 3, 1987, pp. 6–8.

Most comic book versions of The Wizard of Oz have been standard children’s fare, with uninspired illustrations and adaptations that conveyed little sense of the fantasy in Baum’s story telling. However, in the mid-1970s, America’s two biggest comic book companies agreed to pool their resources to translate the real Oz to the comic book page. With some of the best talent in the business behind the project, it was hoped the results would bring Oz to a large, new audience and offer Oz book readers a new medium in which to enjoy the marvelous land.

The idea to issue the Oz series as comic books was the brainchild of Roy William Thomas, Jr., a fan of the original books since childhood. His devotion to Oz did not wane through the years as he became an award-winning writer of comic books and, eventually, editor-in-chief at Marvel Comics Group. A member of the Marvel family since 1965, he scripted many of their stalwarts, including Fantastic Four, Conan the Barbarian, X-Men, Captain America, and Sub-Mariner. He also co-edited a comic book fanzine and contributed to an anthology about comic books.

In the early 1970s, Thomas proposed an Oz comic book to Marvel publisher Stan Lee. The idea received little attention until comic publishers began experimenting with large format “treasury edition” books, running 70–80 pages, with cover prices of $1.00 or more.

Thomas’ idea was to publish a straight retelling of the Oz stories as comic books. In late 1974 or early 1975, just after he stepped down as editor-in-chief at Marvel, he teamed up with artist John Buscema to do the first book in the series. Buscema had been illustrating comic books on and off since 1948, and his major credits at Marvel included The Incredible Hulk, Fantastic Four, Captain Marvel, and Spiderman. Though Buscema had never read the original version of The Wizard of Oz, he was a great admirer of the MGM film.

Buscema recalls that he did one or two sheets of pencil illustrations containing character studies of Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion, making a conscious decision to avoid the familiar characterizations in the MGM version. Not having read the book, his illustrations also differed from Denslow’s interpretations. For example, Buscema’s Scarecrow had a top hat, an old, battered tuxedo coat, and striped pants. The Cowardly Lion was a realistic-looking animal, and Dorothy had blond hair. These drawings were published shortly afterward in the program book for a New York comic book convention and later in the book The Art of John Buscema.

Seven pages of pencil drawings of the story were completed, taking Dorothy from her Kansas farm to her arrival in the Land of the Munchkins and meeting with the Good Witch of the North. Also included in the sketches was the title page depicting Dorothy, Toto, the Scarecrow, Cowardly Lion, and Tin Woodman.

However, the project had gotten no farther than those few drawings when the decision was made to follow the MGM film version instead of the Baum story. Thomas described how that came about in a 1975 letter to David Greene: “It was learned that DC [Comics] had just opened negotiations with MGM to do a comic which would be distributed along with some toys patterned after the Oz characters; MGM even held a banquet attended by Margaret Hamilton, Ray Bolger, and others.”

According to Thomas’ 1975 letter, Marvel beat DC to negotiate a deal with MGM for the rights to do a comic book based on the 1939 film. The Buscema drawings were scrapped, but he and Thomas lost no time in getting to work on the new version. MGM couldn’t give Thomas a copy of the script, so he ended up buying an audio cassette recording of the soundtrack which he listened to over and over to get the dialogue. After a brief telephone conversation with Thomas, and with just a few stills on hand, Buscema did the art entirely from memory.

That was quite a feat, since Buscema recalls he had only seen the movie three or four times including its original release in 1939. He explains, “It left such an impression—I loved it so much. I think it’s a masterpiece. I remembered every bit of it.”

Thomas had to make only a few changes in the order of one or two scenes, and he added the dialogue. He left out the movie lyrics since they were copyrighted separately and would require additional permission for the rights.

When DC found out that Marvel was working on the MGM Wizard of Oz, DC talked about retaliating by coming out with its own 25 cent Wizard of Oz comic. “At the last minute,” Thomas wrote, “Marvel seems to have panicked and struck up a deal with DC to avoid two Oz books at the same time.” No artwork for the DC comic ever turned up, though, and Thomas suspected that DC publisher Carmine Infantino had been bluffing all along.

The deal called for the book to be published as a joint publishing venture by Marvel and National Periodical Publications (DC Comics). However, Marvel writers and artists ended up doing the entire book. It was written by Thomas, who was on contract with Marvel. Buscema and Tony deZuniga, who did the inking, were working almost exclusively with Marvel at the time. DC “just turned it over to us,” Thomas later remarked. “It really didn’t have any input from them at all.” (While the joint venture did not contribute to the Oz production, it did at least pave the way a few months later for teaming up the two biggest superheros in each publisher’s stable, Superman and Spiderman.)

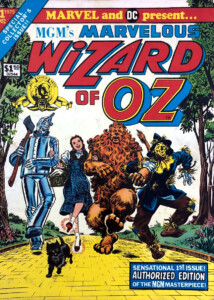

The first Marvel Oz comic, 1975.

MGM’s Marvelous Wizard of Oz hit the stands about the middle of 1975. The front cover by John Romita showed Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, Bert Lahr and Toto in their classic pose dancing down the Yellow Brick Road, with Garland’s ruby slippers sparkling. A diagonal banner across the top proclaimed “Special Collector’s Issue.” The comic book ran 84 pages, including the covers.

The comic book closely followed the details in the movie, including much of the dialogue. The scenes in Kansas were colored in muted gray and blue tones, imitating the film’s black and white scenes.

Because the book stayed so close to the movie, Thomas felt he was not so much a creative writer as an editor. “I don’t believe in adding things for the sake of adding them,” he later said. “Let the originals speak for themselves. I did as little as possible except to guide it.” Paying deference to the authors of the MGM script, Thomas inserted a credit line for Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, and Edgar Allan Woolf.

The result was a loving tribute by Oz fans. The inside covers included stills from the movie; Thomas wrote a biography of L. Frank Baum (which ran a full page) and shorter biographies for the principal actors in the movie. Also included was a double page spread of the map of Oz, dutifully credited to “Prof. Wogglebug, T.E.”

DC had an option to continue the series as a joint venture with Marvel, but turned it down, leaving Marvel to do the next book alone. Therefore, the name of the series was changed in the second book to Marvel Treasury of Oz, and the numbering started over with #1.

Buscema, who had done only the pencil drawings for the first book, was unhappy with the inking by deZuniga. “It meant quite a bit to me,” Buscema later recalled. “I was very upset with the final product. I didn’t want to have anything to do with the book again.”

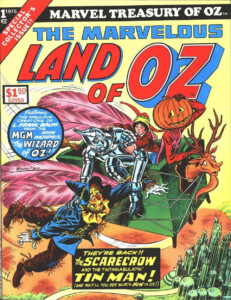

The second Marvel Oz comic, 1975.

For the second book, The Marvelous Land of Oz, Marvel tapped Alfredo Alcala to do the pencils and the inks. Alcala, who had done work for both DC and Marvel since 1972, had illustrated The Incredible Hulk and Conan the Barbarian. He was born in the Philippines where, as a child, he read the Oz books one by one in the school library. He was so looking forward to doing the art for the Marvel Oz series that he bought a whole set of the 14 Baum books for the project.

Work began on Land of Oz with the characters appearing as John R. Neill had originally drawn them. The first few pages were completed when MGM requested the film versions of the characters be used, and Marvel agreed. As a result, Alcala had to redraw several pages that included the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman.

The Land of Oz book, which went on sale mid-November, was the same size and length as Wizard of Oz. It was a literal translation of the Baum/Neill book into comic form. Alcala’s drawings even duplicated many of the details in the original Neill illustrations, with the jarring exception of the characters depicted as Jack Haley and Ray Bolger.

Marvel also stuck with the MGM characters in their third book, Ozma of Oz. Thomas, however, remained uncomfortable with this compromise on the original Baum books, since he preferred those to the film. In his 1975 letter to Greene, Thomas apologized, “Hope the Oz fans don’t hate me too much when, in Ozma, I had to have the Hungry Tiger walk upright to match the MGM Cowardly Lion.” Another change was the elimination of the army of Oz, since the panels would be too crowded with drawings of 26 officers and one private.

As with the earlier book, Alcala did the art for Ozma of Oz and Romita did the covers. A letters page (entitled “Oz and Ends”) was planned to print comments on the first Oz book. Thomas also planned a short article about The International Wizard of Oz Club.

Most. of the work on Ozma of Oz was completed by early fall, and Thomas began on the fourth book, Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz. While on jury duty in late 1975, Thomas had read through a copy of Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, marking it for conversion to comic book dialogue. At this time, still looking to the future, Thomas was thinking as well about buying a copy of The Emerald City of Oz, one of the few books Oz books missing from his collection.

The series was well underway by the time sales figures were known for Wizard of Oz. While the large format of the treasury edition allowed for more creative layouts, it was a marketing nightmare. Comic book stores did not like the oversize volumes because they were too large; book stores would not carry them because they were comic books. No special marketing approach was used for a product which was special both for its contents and appearance. The Wizard of Oz did not reach the regular DC and Marvel audiences, and sales were disappointing.

Financial worries were compounded by the high cost of rights to use the MGM characters. Though they might have added to the appeal of the first book, it is unlikely the characterizations increased readership in the second book. They certainly added to the books’ expenses which probably contributed to the publisher’s reluctance to continue the series.

An advertisement on the last page of Land of Oz announced that Ozma of Oz would go on sale February 3, 1976, “to Gillikin and Munchkin alike.” Alas, not even the Wizard of Oz could have performed the magic necessary to keep that schedule.

“Right now, we plan at least four issues,” Thomas wrote in his letter to Greene just before The Land of Oz hit the stands. “What the situation is with copyright, I don’t know and try not to think about; our lawyers have advised us to go ahead, and so we do.” What the lawyers had determined when the project began is that three Oz books were in public domain. Thomas assumed those were Wizard, Land, and Ozma. Unfortunately, as Thomas later found out, the lawyers’ list included not Ozma of Oz, but The New Wizard of Oz, which was just a new name for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz refiled at the Copyright Office in 1903.

The situation was certainly complicated. Ozma of Oz was copyrighted by Baum in 1907, and the copyright was renewed by The Baum Estate when it expired 28 years later in 1935. Under the law in effect at the time, the renewed copyright was set to expire in another 28 years and could not be extended after 1963. However, a series of Congressional enactments beginning in 1962 extended the copyright automatically until the total duration was 75 years. That 75 year period did not end until 1982.

In other words, the Ozma of Oz comic book that Marvel had ready for the press was still under copyright protection. Thomas argued that Marvel should buy the rights from The Baum Estate so it could go ahead with the series. However, there was little enthusiasm for the idea, since the first two books had not sold well. And no one else seemed to want the additional trouble and expense necessary to publish the third book.

Thomas held on to the art for several months. During that time, the dialogue balloons and art corrections started falling off. The drawings reached such a stage that some of them would have to be redrawn if they were ever printed. Finally, he returned them to the Marvel office. Later, he tried to get a copy of the drawings but found out they were lost. “That was the end of Marvel’s Oz adventures,” he later recounted.

The series is remembered fondly by its creators who still harbor hopes for a resurrection. In the introduction to The Oz-Wonderland War comic ten years later, Thomas wrote, “I wish Marvel, MGM, and (in the case of the first comic) DC would get together to reissue the material. It was better fare, art-wise, than most fan-favorite stuff then or today and might do well if it were packaged at a size somebody can actually hold easily in his hands.”

Alcala, too, felt a sense of loss over the cancellation of the series. He still holds out hope that someday he can do the rest of the Oz stories as comic books.

With half of the Baum Oz books now in public domain, it might finally be practical to bring out the Oz series in comic book form . . . or to hunt down the lost Ozma of Oz drawings and publish them. For any Oz fan who likes comic books and has an entrepreneurial bent, there just might be an opportunity here.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.