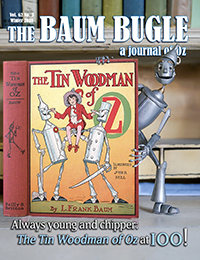

Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 62, no. 3 (Winter 2018), pgs. 8–11

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Crotzer, Sarah K. “The Rescue of the Tin Woodman: An Appreciation.” Baum Bugle 62, no. 3 (2018): 8–11.

MLA 9th ed.:

Crotzer, Sarah K. “The Rescue of the Tin Woodman: An Appreciation.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 62, no. 3, 2018, pp. 8–11.

(Note: in the printed version of this article, the author of the Lit Brick webcomic was misnamed. This has been corrected in the digital presentation. The endnote citations have also been adjusted for clarity.)

I have always loved two of Baum’s characters more than any others: the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman. They represent the best of Baum’s imagination, and they are the purest distillation of his philosophy that people should celebrate their differences as much as their commonalities. I love the way he always places them in the background of bigger adventures, bickering goodnaturedly with each other, sometimes long into the night. They are, as a small child wrote in one of my antique Oz books (with connective arrows between their pictures!), “very good friends.”

They are also people whose bodies betray them on a regular basis. As a child with a physical disability, I responded to the way they just picked themselves up and kept going, never held back for long; as an adult, ever more aware of my own limitations, I recognize their fear of rain and lit matches. They aren’t supermen, but like everyone in Oz, they’re persistent—and of course, they always have friends to back them up. Dorothy, Ozma, and the others never linger on the two men’s fragility; they find more straw, or they look for an oil can, and on we go.

The Tin Woodman of Oz is the only book in the Famous Forty to place their friendship firmly in the spotlight, so it’s no surprise that it became my favorite almost right away. It’s full of humor, adventure, and the general strangeness that permeates all of the best Baum books.

You would think that a book geared around famous characters would meet a welcome audience, but words I’ve heard to describe Tin Woodman range from “depressing” to “nightmarish.” The esteemed Martin Gardner, who claimed to have reread the book “with high pleasure” for a 1996 Bugle article, found its climax “deeply disturbing”1 and suggested it was “the least satisfactory of Baum’s Oz books.”2 My personal belief is that some readers look for what they want from a book of this type—the twelfth, it should be remembered, in a series—instead of appreciating what it actually offers. The story has depth that places it among the top Oz books ever written.

On the other hand, by the time Baum wrote the book, the Tin Woodman himself was practically a cipher. His friendship with the Scarecrow was introduced to reflect the popularity of Fred Stone and David Montgomery’s stage personas; together, they “headline” The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904), a book that was almost named after their “Further Adventures.” While the Scarecrow remained a protagonist throughout the series, however, the Tin Woodman rapidly took a back seat, often appearing only to perpetuate the double-act with his straw-stuffed friend. In The Road to Oz (1909), he is the first to host Dorothy and her friends on their arrival in Oz; he shows up at the end of The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913) to provide the moral lesson. He doesn’t appear at all in the books from 1914-16, with only a brief cameo in The Lost Princess of Oz (1917). As a result, the reader’s impression of the Tin Woodman often relies on the memory of earlier books, and it is easy to ignore the shift in his characterization.

When most readers talk about the Tin Woodman, they describe him as he appeared in a single novel: 1900’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. In a recent talk with James Ortiz, director of The Woodsman, I mentioned that the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman always remind me of classic film stars James Stewart and Henry Fonda—best friends in real life, with wildly different personalities. “Well, yeah,” said James, “if Henry Fonda burst out crying every six seconds.” That’s what most folks remember: the character’s emotional vulnerability, his insecurity, his anguished outbursts. Once his arc is satisfied at the end of Wizard, and the influence of Stone and Montgomery is felt, most of those elements fade away to be replaced by a single, overriding trait: pride.

There is no hint of the Tin Woodman’s latent dandy-ism in Wizard. Although he is reconstructed by the Winkies with many patches on his body, “as the Woodman [is] not a vain man, he [does] not mind the patches at all.”3 His humility is reversed to comedic effect in Marvelous Land; when the Woodman first appears “thickly smeared in putz-pomade,”4 his enthusiastic embrace sends the Scarecrow to the laundry. The two friends spend the rest of the book debating who is wealthier, ending in Ozma’s moral lesson that they both share “the riches of content.”5 Baum isn’t done, though; the gag accelerates, and soon, the Emperor of the Winkies lives in a world of ironic opulence: in Road, he is “proud of his new tin castle,” with all the furniture “made of brightly polished tin.”6 We are told that “even the floors and walls [are] of tin,” and Dorothy declares the well-polished tin dishware “just as good as silver.”7 Readers are left to their own judgments what use this all is to a man who neither sleeps nor eats.

The Tin Emperor may have been a bit grandiose in earlier appearances, but the character readers meet at the start of The Tin Woodman of Oz is downright arrogant. Although the Tin Woodman is described by his servant as “a kind master, as honest and true as good tin can make him,”8 he is certainly fond of blowing his own horn. “Being a stranger, [you] are no doubt curious to learn how I became so beautiful and prosperous,” he tells Woot the Wanderer.9 Celebrity seems to have gone to his head.

Woot sets the book’s plot in motion when he calls the Tin Woodman out on a claim. “Had the heart the Wizard gave you been a Kind Heart,” he says, “you would have gone back home and made the Munchkin girl your wife.”10 The Tin Woodman is surprised to hear Woot’s observation, but he doesn’t see it as a personal failing. Instead, it’s a temporary problem he can fix. “It is not the girl’s fault that I no longer love her,” he says pragmatically, “and if I can make her happy, it is proper that I should do so.”11 This is a wonderful setup for a journey of personal discovery. Later in this issue, J.L. Bell examines the thematic unity of the novel as a whole, but already we see the signs of a character arc. The Woodman’s overwhelming pride in the early chapters is tested again and again, with increasingly traumatic results: first, he is changed into a tin owl by Mrs. Yoop, which readers are told cannot be undone; he takes this on bravely, saying, “I’m not going to allow my new form to make me unhappy.”12 After magic provides a cure, he finds his individuality threatened by the existence of the Tin Soldier, who resembles him almost exactly aside from the addition of a tin heart. Still he remains undaunted, accepting the Soldier as a brother and suggesting that Nimmie Amee choose between them.

The visit to Ku-Klip’s workshop is the first overt sign the book is heading into unusual territory. A century of child readers have been fascinated by the Woodman’s discovery of his former head, alive and grumpily vocal, in a cabinet. John R. Neill’s illustration adds streaming tears to the Tin Woodman’s face; he looks as if he’s having a complete emotional collapse. The actual reaction in the text is muted but significant: “The poor Emperor felt so bewildered that for a time he could only stare at his old Head in silence.” When he finally recovers, he compliments the Head: “You’re almost handsome—for meat.”13

It’s a strange moment, all the more so because of Baum’s matter-of-fact tone. It teeters on the edge of the comic and macabre, which was likely Baum’s intent. This scene, more than any other, highlights Baum’s skill and makes a lie of the truism that he was a good storyteller but a poor writer. As Disney’s Return to Oz learned to its detriment, this kind of scene is pure nightmare fuel if visualized literally. I think Jodie Troutman’s Lit Brick webcomic comes closest to Baum’s tone with a series of silent movie-style reactions: it’s funny—but it’s horrific! It’s horrific—but it’s funny!

This scene is also the first in which the Tin Woodman realizes that his pride may have been misplaced. Although he claims to his Head that “you and I are one,” the Head flatly denies it: “It would be unnatural for me to have any interest in a man made of tin.”14 The Tin Woodman leaves discouraged, noting “thoughtfully” that “I thought I had a more pleasant disposition when I was made of meat.”15

This sequence sets the stage for Baum’s dénouement. Nimmie Amee is found, but she is “more amused than pleased” to see her old lovers, commenting “even sweethearts are forgotten after a time”.16 Her husband, Chopfyt, is made up of the Tin Woodman and Tin Soldier’s spare parts, and when Nimmee Amee claims that both former suitors “deserted” her, they are ashamed.17 When the Tin Woodman leaves, he has to be content with knowing that Nimmie Amee is happy—absolving him of his responsibility—and that it is “her own choice.”18

The Tin Woodman of Oz, then, is about growth. That’s a shock in a series sometimes described, not entirely inaccurately, as a fantasy-based Bobbsey Twins or Hardy Boys. It’s particularly odd after such a long period of narrative stasis, too. In part, that may indicate the author’s interest: the depth and maturity of the better Oz books often seem to indicate Baum’s own investment in his work.

After several books that rehash silent film scenarios, stageplays, and unfinished early novels, Baum’s return to form in Lost Princess is heralded by that book’s moral complexity and oddly mystical conclusion. Suddenly, it feels as if he has something to prove again, and in Tin Woodman he goes a step further: he dares to write an uncomfortable novel.

It’s an astonishingly brave act for an author to bust up the cozy status quo by forcing a beloved characters to face his past—literally!—and no one knows what prompted Baum to do it. The idea may have come from long days working in the garden or dreams Baum had in the middle of the night. (I picture him bolting upright in bed, pencil in hand. “Maud!” he cries. “To the wallpaper!”) It may be he simply determined to answer a question readers had sent in for almost 20 years: “Whatever became of that Munchkin maiden?” Finally, and significantly, there is the suggestion that he was inspired by World War I and the soldiers returning home with limb loss and “shell shock”—the term then used for posttraumatic stress disorder.

The source that remains unacknowledged is Baum’s own self-awareness. His middle age had been a dizzying blur of success, celebrity and brushes with the newest technological wonders. Not all of his endeavors had succeeded, but he’d managed to keep from total financial collapse, and—according to more than one account—fostered a sizeable ego on the side. At times, he probably felt indomitable, but by 1917, age and ill health had taken their toll. It’s easy to envisage a Baum who got up in the morning and saw himself looking greyer and more haggard with every passing week. “Whose Head are you?” he might have asked the face in the bathroom mirror. I understand that guy, and I think I understand what he’s trying to say in this book: in time, we are all replaced by other versions of ourselves.

That’s the dark side of what made me feel so hopeful as a child: the celebration of differences and the uniqueness of the individual ignores, or at least avoids, how rarely and briefly we are ever at our “best.” Everyone’s body ages; everyone loses their skills; everyone, frankly, will need new parts. No one escapes the Witch’s cursed axe, and sooner or later, we all look back to discover we are not the person we were or thought ourselves to be. In the bigger scheme of things, none of us is special.

Fortunately for the Tin Woodman, that’s okay; his is a lesson to be learned, not a punishment to endure. The Tin Woodman of Oz seeks to redeem its self-styled hero: not in a grand wedding to Nimmee Amee, but in a quiet dinner with old friends. They’re our friends, too, and we wrap up the story without worrying whether the dishes are tin or silver. This is Baum’s idyllic scenario: everyone together, enjoying the company, looking forward to the next adventure. There is no arrogance here—everyone is equally special to each other.

Because Tin Woodman was published so close to the end of Baum’s life, we don’t know to what degree this book might have influenced his future plans for Oz. Ultimately, the Tin Woodman is never integral to another Baum novel; in fact, he doesn’t share protagonist duties again for twenty years, until Ruth Plumly Thompson’s Ozoplaning with the Wizard of Oz. As a result, his eponymous novel feels like a little gem late in Baum’s run: rich and strange and full of meaning.

Forgive me for saying so, but I find it deeply satisfying.

1 Gardner, “Tin Woodman,” 14.

2 Gardner, 15.

3 L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Chicago: Geo. M. Hill, 1900), 161.

4 L. Frank Baum, The Marvelous Land of Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Britton, 1904), 123.

5 Baum, Marvelous, [287].

6 L. Frank Baum, The Road to Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Britton, 1909), 164.

7 Baum, Road, 166.

8 L. Frank Baum, The Tin Woodman of Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Britton, 1918), 15.

9 Baum, Tin, 21-22.

10 Baum, Tin, 32.

11 Baum, Tin, 33.

12 Baum, Tin, 94.

13 Baum, Tin, 212.

14 Baum, Tin, 215.

15 Baum, Tin, 216.

16 Baum, Tin, 273.

17 Baum, Tin, 276.

18 Baum, Tin, 287.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.