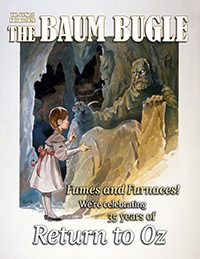

UNPLEASANT DREAMS

The Role of Electroshock Therapy in Return to Oz

by Karen Diket

Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 64, no. 2 (Autumn 2020), pgs. 17–19

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Diket, Karen. “Unpleasant Dreams: The Role of Electroshock Therapy in Return to Oz.” Baum Bugle 64, no. 2 (2020): 17–19.

MLA 9th ed.:

Diket, Karen. “Unpleasant Dreams: The Role of Electroshock Therapy in Return to Oz.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 64, no. 2, 2020, pp. 17–19.

(Note: In print, this article contained a typo that misnumbered two endnotes. This has been corrected for the online version.)

At the beginning of Return to Oz (1985), Dorothy is sent to be treated with electroshock therapy to eliminate her “unpleasant dreams.”[1] Aunt Em, troubled by Dorothy’s personality and behavioral change as a result of the tornado, has brought her to Dr. Worley for electric healing. From this point forward, viewer expectations of a fun-filled adventure in Oz are shattered. Director Walter Murch’s dark storytelling and imagery shocked his initial audience in 1985 and continues to shock many viewers today. Why would the first thirty minutes of the film be devoted to exploring the concept of electroshock therapy and Dorothy’s supposed need for this treatment?

Electroshock therapy is credited to the Italian psychiatrist and neurologist Ugo Cerletti. Beginning in 1931, Ugo Cerletti conducted experiments on animals to find new treatments for schizophrenic patients. In 1933, psychiatrists used insulin therapy, which could have side effects of “irreversible neurological damage as well as terminal coma.”[2] The use of Cardiazol therapy followed in 1935, along with prefrontal leucotomy—later renamed lobotomy—in 1936. These were all dangerous operations, so Cerletti and his assistant, Lucino Bini, turned to electricity as an easier and safer way to treat mentally ill patients.

In 1938, a patient suffering from delirium and hallucinations became the first human to undergo electroshock therapy treatment. Before treatment, the patient was unable to lucidly communicate or function on his own, but after having multiple electroshock treatments, his hallucinations and delirium disappeared, leaving him lucid and wanting to help himself and others. This case marked the beginning of electroshock therapy for therapeutic purposes in the treatment of schizophrenia, manic-depressive illness, major depression episodes, and more. Finally, in 1940, the New York State Psychiatric Institute introduced Electroshock Therapy to the United States.[3]

Having made a success of their treatment, Cerletti and Bini wrote extensively within the psychiatric field, leading to the publication of Shock Treatment in Psychiatry: A Manual (1941). Subsequent books followed: An Introduction to Physical Methods of Treatment in Psychiatry in 1944 and Shock Treatment and Other Somatic Procedures in Psychiatry in 1946. Electroshock therapy was widely used by the U.S. military during World War II, and by the 1950s, it had become a standard treatment for depression.[4]

Electroshock Therapy, relabeled as Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT), remains a controversial psychiatric treatment due to concerns that it creates permanent memory loss and confusion. After the ECT procedure, patients generally awaken confused and without memory of events surrounding the procedure. ECT treatments may be repeated three times a week over a four-week period, and it is often recommended that patients be required to maintain a regimen of medication to reduce the chance of relapse after ECT treatments. Some studies have shown promising results, “citing eighty percent improvement in severely depressed patients, after ECT.” Other studies appear to demonstrate that relapse remains likely “even for patients who take medication after ECT,” and according to some, “no study proves that ECT is effective for more than four weeks.”[5]

Is ECT, then, a plausible solution for Aunt Em and Uncle Henry to “help” Dorothy? Electroshock Therapy did not exist in the time period established for Return to Oz: Kansas, October 1899. Why was Electroshock Therapy included in the plot if it is historically inaccurate?

Walter Murch answered this question in an interview for The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film. Murch wrote the screenplay for Return to Oz alongside Gill Dennis, a filmmaker whose greatest career accomplishment would be the screenplay for Walk the Line (2005). Dennis owned Michael Lesy’s book, Wisconsin Death Trip (1973), which contained newspaper stories and photographs from Wisconsin in the 1890s. Murch and Dennis used this book for insight into the real story of what life would have been like in this time period. Their research into what people now view as the “simple life” of the “good old days” revealed “a lot of insanity, disease, barnburning, and revenge.”[6] Murch asked himself:

What if the first story, The Wizard of Oz, had really happened, as reported by a local newspaper?

That a tornado came and blew an old couple’s house away, destroyed it—which happened all the time—and a girl, the niece of the couple, survived and when she was finally found, miraculously alive, she had a story to tell about where she’d been. What would her aunt and uncle think? What would be the real conditions for that family? What if they had to build a new house, take out a second mortgage? And the uncle had broken his leg in the tornado, and was trying to survive as a farmer? And their niece kept talking about this magical place she’d been. They’d say, Don’t talk like that, there isn’t a place like that! What should she do? Should she deny that it had happened to her? That’s Dorothy’s dilemma at the beginning of our film. Return to Oz is a fusion of the reality of Wisconsin Death Trip and the fantasy of Ozma of Oz.[7]

Return to Oz is based on realism, not romanticism. Farm life at the turn of the twentieth century was a life of subsistence. The sidebar on this page aptly demonstrates Aunt Em’s desperate need for help with the farm chores.

Dorothy is not helping; she keeps thinking and talking about Oz, a place no one knows about, and her thoughts about Oz keep her awake at night. Dennis and Murch introduced ECT to the script as a graphic, last-resort solution to a real-life problem, allowing the urgency of the Gales’ situation to hit the viewer with a greater impact.

Many viewers of Return to Oz found Electroshock Therapy a disturbing element for a children’s Oz film. The National Research Group held a test screening of Return to Oz with a mixed group of parents and children. Approximately 75% of the parents judged the film to be too scary for children below age 12, but when the proctors of the test spoke with the children, “they said they liked it a lot[;] they had a great time.”[8]

Children tend to view films solely on a surface level as momentary entertainment, and Return to Oz contains mystery, adventure, and exciting new characters that engage child viewers’ imaginations, such as Jack Pumpkinhead, Tik-Tok, Billina, and Mombi with her hallway of heads.

Electroshock Therapy also reinforces the central theme in Return to Oz of fantasy versus reality. Doctor Worley explains to Dorothy how his “electrical marvel” will eliminate her “unpleasant dreams.”[9] Doctor Worley’s, as well as Aunt Em and Uncle Henry’s, intent is to destroy Dorothy’s dreams of Oz and place her firmly on the ground of living in reality. Likewise, Doctor Worley, personified in her “dream” as the Nome King, strives to eliminate Dorothy and those who remember Oz (Dorothy’s fantasies). Dorothy’s mind created a character that wanted to destroy her memories, just as Electroshock Therapy will do.

The Nome King’s ultimate goal is for no one to remember Oz so he can become “human.” What does it truly mean to be human? Can humans live in reality and still fantasize and dream of alter-realities? Children enjoy living in a fantasy world as well as reality, but the adults of this film do not believe the two can coexist—and, it seems, parents in 1985 agreed. Therefore, Electroshock is a device by which to eliminate Dorothy’s vibrant fantasy world of Oz, and it has become a reason for some viewers to eliminate their appreciation of Return to Oz, as well.

Sidebar: Farm Wife, 1900

An eyewitness account entitled “Farm Wife, 1900” vividly depicts what life for Aunt Em or any farm wife was like. This typical daily schedule is paraphrased from the account:

4:30 A.M.: Wake up, get dressed, comb hair, set fire in stove, sweep floors, cook breakfast.

While other family members eat: Strain away morning’s milk, fill husband’s dinner pail.

5:30 A.M.: Husband leaves for work. Drive cows half mile to pasture, come back, take horse to a spring for water, come back, young calves are turned out, hogs fed, turn out chickens and put out feed and water for them.

6:30 A.M.: No breakfast as yet. Make beds, straighten up living room, go clean kitchen, and get a few bites to eat during the process.

7:15 A.M.: Wash and dress children, churn butter.

8:00 A.M.: Hoe weeds in garden.

11:30 A.M.: Come inside, comb hair, eat cold dinner, put out feed and water for chickens, set a hen, sweep floors again, sit down to rest for a few minutes and read.

1:00 P.M.: Sweep the door yard, make and sow a flower bed, dig around some shrubbery, go back to garden to hoe until time to do nighttime chores.

4:00 P.M.: Go to house, get supper, prepare something for the dinner pail tomorrow. When dinner is ready—set aside. Pull a few hundred plants of tomato, sweet potato or cabbage for transplanting, set in cool, moist place, water horse and put in barn, call the sheep and house them, go after the cows and milk them, feed the hogs, put down hay for three horses, put oats and corn in their troughs, set those plants, come in, and fasten up the chickens. It is dark.

8:00 P.M.: Husband is home. Eat supper, make the beds ready, children and husband go to bed, wash the dishes, and get things in shape to make breakfast tomorrow.

9:00 P.M.: Say a short prayer and retire for the night.[10]

[1] Return to Oz, directed by Walter Murch (1985; Burbank, CA: Buena Vista Home Entertainment, Inc., 2004), DVD.

[2] Alessandro Aruta, “Shocking Waves at the Museum: The Bini-Cerletti Electro-shock Apparatus,” Medical History 55, no. 3 (July 2011): 407–412. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3143851.

[3] Andy Behrman, “Electroshock Therapy A Brief History of Electroshock Therapy (ECT),” Electroboy, accessed November 20, 2016, http://www.electroboy.com/electroshocktherapy.htm (site discontinued).

[4] Edward Shorter, “The History of ECT: Unsolved Mysteries,” Psychiatric Times, MJH Life Sciences, February 1, 2004, http://www.psy-chiatrictimes.com/articles/history-ect-unsolved-mysteries.

[5] “Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT),” Mental Health America, accessed November 22, 2016, http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/ect.

[6] Walter Murch, in The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, by Michael Ondaatje (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002), 291.

[7] Murch, in The Conversations, 292.

[8] Bobby Carroll, “Return To Oz 1985 (or how a little seen flop sequel managed to scar a generation),” Bobby Carroll’s Movie Diary (blog), September 27, 2015. https://bcmoviediary. com/2015/09/.

[9] Return to Oz, DVD.

[10] “Farm Wife 1900,” EyeWitness to History, Ibis Communications, 2007, http://eyewitness-tohistory.com/pffarmwife.htm.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.