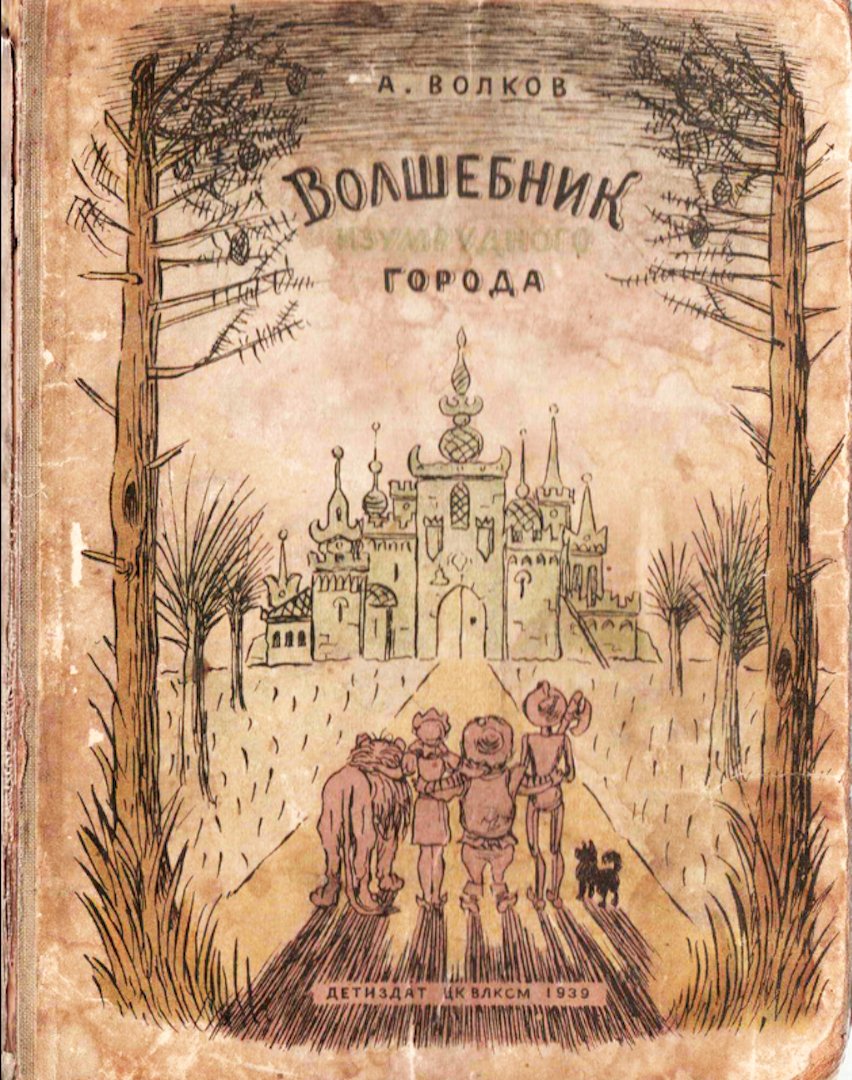

In 1939 the state publishing house Detgiz in Moscow published a new children’s book. International copyright law was not recognized by the Soviet Union so Volshebnik izumrudnogo goroda (The Wizard of the Emerald City), by mathematics teacher Aleksandr Malentyevich Volkov (1891-1977), appeared under Volkov’s name with no mention of L. Frank Baum.

In 1939 the state publishing house Detgiz in Moscow published a new children’s book. International copyright law was not recognized by the Soviet Union so Volshebnik izumrudnogo goroda (The Wizard of the Emerald City), by mathematics teacher Aleksandr Malentyevich Volkov (1891-1977), appeared under Volkov’s name with no mention of L. Frank Baum.

More than a straight translation, Volkov added original side adventures in place of some of Baum’s and never used the word “Oz.” He renamed the characters. Dorothy is Elli, Scarecrow is Strashila, and the Cowardly Lion is Leo. The Tin Woodman becomes an Iron Woodman largely because Volkov knew that tin doesn’t rust. Elli’s faithful little dog Totoshka speaks in Volkov’s tale, Baum’s Kalidahs become Saber Tooth Tigers, the Wizard is named Goodwin, and the witches are Villina, Bastinda, and Gingema.

Illustrated by Nikolai Ernestovich Radlov (1889-1942) the book quickly sold 50,000 copies. The 1941 edition reportedly had a print run of 227,000 copies.

We now know that Volkov read The Wizard of Oz to improve his English at some risk; it was not easily available in the Soviet Union and was not state-approved. The story captured his imagination; when he read it to his own children they loved it.

The success of his book led to a new edition illustrated by Leonid Viktorovich Vladimirskii (1920-2015). Volkov edited his own text for this revised 1959 version. It became wildly popular in the Communist Bloc. So popular, in fact, that just like Baum, Volkov penned his own original sequels. With time he tweaked the story until Aunt Anna and Uncle John become Elli’s parents. And Volkov himself became a beloved children’s author, writing more than 50 books.

The success of his book led to a new edition illustrated by Leonid Viktorovich Vladimirskii (1920-2015). Volkov edited his own text for this revised 1959 version. It became wildly popular in the Communist Bloc. So popular, in fact, that just like Baum, Volkov penned his own original sequels. With time he tweaked the story until Aunt Anna and Uncle John become Elli’s parents. And Volkov himself became a beloved children’s author, writing more than 50 books.

Now ingrained in Russian culture, the “Magic Land” books first came to life in puppet shows and on radio followed by stage musicals, live-action movies, and stop-motion television. Sculptures are found on the streets, postcards are mailed to friends, toys and games are playthings of Russian children. A computer-animated film Urfin Jus i ego derevyannye soldaty (Fantastic Journey to Oz based on Volkov’s The Wooden Soldiers of Oz), was released in 2017, followed by Fantastic Return to Oz in 2019.

Now ingrained in Russian culture, the “Magic Land” books first came to life in puppet shows and on radio followed by stage musicals, live-action movies, and stop-motion television. Sculptures are found on the streets, postcards are mailed to friends, toys and games are playthings of Russian children. A computer-animated film Urfin Jus i ego derevyannye soldaty (Fantastic Journey to Oz based on Volkov’s The Wooden Soldiers of Oz), was released in 2017, followed by Fantastic Return to Oz in 2019.

Accepted as his creations, Volkov’s headstone is illustrated with Elli and her friends.

The 1939 MGM film was introduced to Russian audiences in the 1970s. Direct translations of Baum’s original story became available in the USSR in 1983 followed in 1991 with his sequels. Magic Land has been translated into other languages and is sometimes used as an English language text book. It is a more widely known version of the story than Baum’s in some countries. Modern Russian authors continue the series and a Friends of the Emerald City group is based in Moscow. A new reference book, Oz Behind the Iron Curtain: Aleksandr Volkov and His Magic Land Series (Erika Haber, Univ. Press of Mississippi) was published in 2017.

While Club members and devoted fans are likely to have heard about Magic Land, it is not common knowledge with the public. For the next six months or so, the Oz Club’s case (below, left) in the Oz Museum, Wamego, Kansas, offers a look at Russia’s Oz and its creators.