WOGGLE-BUG ON THE HEARTH

by Patricia Tobias

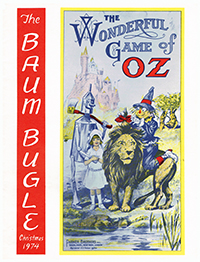

Originally published in The Baum Bugle, vol. 18, no. 3 (Christmas 1974), pg. 8–11

Citations

Chicago 17th ed.:

Tobias, Patricia. “Woggle-Bug on the Hearth.” Baum Bugle 18, no. 3 (1974): 8–11.

MLA 9th ed.:

Tobias, Patricia. “Woggle-Bug on the Hearth.” The Baum Bugle, vol. 18, no. 3, 1974, pp. 8–11.

” . . . there be bugs and bugs.” Nick Chopper in “Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz,” October 16, 1904

Maybe education was as distasteful to L. Frank Baum as bugs were. Certainly he made Professor Woggle-Bug[1] into one of the most noticeably flawed residents of Oz.

The Woggle-Bug’s problems were not immediately apparent. His first appearance (in The Marvelous Land of Oz) was dignified. He presented his calling card to the Scarecrow and told how, before he became magnified and educated, he had lived on a hearth in the classroom of Professor Nowitall (“the most famous scholar in the land of Oz”), where he acquired a veneer of scholarship. For a science lesson one day, Nowitall captured this wogglebug’ and magnified him on a screen. The bug bowed politely, then escaped, still magnified. In the course of his wanderings, he saved the ninth life of a tailor who gratefully fitted him with a stylish suit. Somewhat later, he met Tip, the Tin Woodman, the Sawhorse, Jack Pumpkinhead, and the Scarecrow (to whom he presented his card), all headed for the Emerald City. By this time, he had dubbed himself H.M. (for Highly Magnified) Woggle-Bug, T.E. (for Thoroughly Educated).

But the worst of the Woggle-Bug’s annoying characteristics soon appeared: he delighted in making bad puns. Even the kind-hearted Tin Woodman threatened to chop him up unless he controlled the tendency, but the W oggle-Bug justified himself by saying, “It requires education of a high order,” and thus gave the first sign of his developing academic snobbery. Although over the years his pun habit was eventually palliated, he never stopped thinking of himself as better than most of those around him because he was intellectually their superior.

When H.M. and his new-friends reached the Emerald City, it had been taken over by a gang of dissatisfied young women led by General Jinjur, who threatened to make green turtle soup of the Woggle-Bug. To escape the captured city, the travelers built a flying Gump, brought it to life with Dr. Nikidik’s magic powder of life (which had also brought Jack Pumpkinhead and the Sawhorse to life), and flew away. During a landing in a jackdaws’· nest, the Gump broke, and the only way the group could see to fix it was with Nikidik’s wishing pills, a supply of which happened to be available. The Woggle-Bug saved the day: he was the only one who could take the pills (they were too noxious for Tip, and nobody else knew how to swallow).

When, at the end of The Land of Oz, Tip became Princess Ozma, she named the Woggle-Bug Public Educator and royal advisor. Why? Well, the position was one for which H.M. might be considered qualified-he was the most educated wogglebug in Oz. Still, three years on a hearth is not necessarily a thorough education. The Scarecrow might have been better for the job; not only did he have brains, but there is evidence that he used them with some regularity.

Maybe the Woggle-Bug’s appointment was a payoff for political favors: he saved Ozma/Tip from the jackdaws’ nest and was rewarded with a newly invented government post. Although it sounds like the wrong sort of thing to find in a perfect fairyland, such payoffs have occurred frequently in Oz: for example, in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, a humbug was raised to Official Wizard because he had once maintained a caretaker-government; in another example, Dorothy herself was made a princess, yet apparently did no government work at all.

Baum may have had Ozma choose the Woggle-Bug for the job because it permitted a suitable statement about education. Baum created in the bug. an unlikeable, unfeeling, pompous character who made bad jokes. He may have intended to convey, through the Woggle-Bug and his school, a message to suggest that scholars are either lazy or frauds, and that the academic approach to life is not relevant, a claim still made by many students. Baum certainly had good reason to dislike institutionalized education. As a child with a weak heart, he was tutored at home until he could be sent off to military school. “One day Cadet Baum was severely disciplined for looking out of the window at the birds while he should have been preparing his lesson. His resentment of the penalty brought on a heart attack. . . .”[2] When he recovered, he returned to the comfort of private tutoring at home.

Of course the Woggle-Bug may have been appointed because he had proven himself worthy of an important position in which he could use his education. Whatever the reason, though, his career progressed rapidly. In a relatively short time, he went from a simple little woggle-bug on the hearth to Mr.[3] H. M. Woggle-Bug, T.E. Not too much later, he became the Public Educator of all Oz. One may marvel at the sudden rise in his fortunes.

Some time between The Land of Oz and Ozma of Oz, he was named President of the College of Art and Athletic Perfection. After The Land of Oz, his achievements are referred to often, but he has participated in only three real adventures recorded in the rest of the Oz books. They are in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz by Baum, The Royal Book of Oz by Ruth Plumly Thompson, and The Wonder City of Oz by John R. Neill.

Dorothy and the Wizard is the story of Dorothy’s return to Oz with O. Z. Diggs, who then remained in Oz as Official Wizard. He brought with him nine tiny piglets, one of which he presented to Ozma as a gift. When the piglet disappeared, Dorothy’s kitten Eureka was accused of having eaten it. At the murder trial, the Woggle-Bug as Public Accuser summed up:

“I say I see the criminal, in my mind’s eye, creeping stealthily into the room of our Ozma and secreting herself, when no one was looking, until the Princess had gone away and the door was closed. Then the murderer was alone with her helpless victim, the fat piglet, and I see her pounce upon the innocent creature and eat it up-“

“Are you still seeing this with your mind’s eye?” inquired the Scarecrow.

“Of course; how else could I see it? And we know the thing to be true, because since the time of that interview there is no piglet to be found anywhere.”

This sort of logic might not work in an American court, but it won the case against Eureka.[4] The Woggle-Bug had proved himself to be a good Ozian lawyer as well as an intelligent insect.

He is not recorded as having done anything more of historical importance until The Royal Book, when he appointed himself Great, Grand Genealogist of Oz and began writing a catalogue or registry of Oz royalty. He snobbishly excluded the Scarecrow because of the straw man’s humble origin. Concern about being a commoner led the Scarecrow to search out his past and ultimately to find that he was once His Supreme Highness Chang Wang Woe of Silver Island. The Woggle-Bug admitted his mistake and corrected the omission in his book.

As Ozma’s ozlection man-ager (only those of man-age could vote) in The Wonder City, the Woggle-Bug suggested that ballots be right shoes so that people could exert their rights and throw their soles into the election, an obvious case of backsliding into the old, nearly cured, pun habit. When the Heelers stole the election results, H. M. suggested that everyone weigh himself (a new way of voting). Weights would be given alternately to candidates Ozma and Jenny Jump; whoever came in heavier would win. Ozma won by one person’s weight.

And that covers the Woggle-Bug’s major exploits in the Oz books. However, his most publicized and detailed records of activities occur in no Oz book at all. The Waggle-Bug play opened (see “How Did the Woggle-Bug Do?” by Michael Patrick Hearn in this issue of the Bugle), the “Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz” newspaper series was published, and so was The Woggle-Bug Book, all in the three years between The Land of Oz and Ozma of Oz. Furthermore, two songs were written that had the Woggle-Bug’s name in the title.[5] The bug was in the public ear and eye more than ever before or ever again.

The “Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz” series, which ran once a week from the summer of 1904 until early the next year, was twenty-six stories written by L. Frank Baum and illustrated by Walt McDougall (together with a promotional page that ran the week preceding the first story). In them, the Woggle-Bug, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, Jack Pumpkinhead, the Sawhorse, and the flying Gump visited North America with the permission of Ozma. They flew all over the United States, and at one point found their old friend Dorothy[6] in time to help her celebrate her birthday. The Woggle-Bug created magic trees and fish to entertain Dorothy’s guests.[7] In another episode, he found a turkey for a little girl who was about to celebrate Thanksgiving without one.

In the 1904 “Queer Visitors” stories. H. M. played an important part, particularly when he came up with a solution to the group’s current problem at the end of each adventure. For example. in the first story (reprinted in The Baum Bugle, Autumn 1974), the visitors were lost and the Woggle-Bug deduced their location. A few stories later, the Scarecrow had his face repainted by a woman who gave him a face that belonged to someone else. The Woggle-Bug knew whose it was. These and other stories in 1904 were accompanied by a quiz that concluded with the catchphrase, ”What Did the Woggle-Bug Say?”

In 1905, during the last months of the series. the format changed to include more about curious people in America. The catchphrase was dropped, and the visitors were usually present in the stories only in minor roles.[8]

The “Visitors” series gave the Woggle-Bug a chance to relax and be friendly. His many helpful suggestions made him more a real leader than was the familiar show-off Woggle-Bug of The Land of’ Oz.

A spinoff from the “Visitors.” Baum’s The Woggle-Bug Book concerns some of the Woggle-Bug’s American adventures during a period when he was separated from other Ozian visitors. Its tone differs greatly from both the “Queer Visitors” and the Oz books. In the beginning, the Woggle-Bug fell in love with a clothing-store mannequin wearing a plaid dress and a sign (“Greatly Reduced-$7.93”). After digging ditches to earn the bride-price, he returned to the store to discover that his love was for the dress, not for the wax dummy, and that the dress had been sold. His misfortune is compounded by the readers’, for the book gets progressively worse. He traveled everywhere in search of the cloth that held his love, regularly making comments that today would be recognized as racist. In the end he won the object of his affection.

The Woggle-Bug’s personality in his Book is quite different from what we see in the more reliable historical sources. Still, the Book and The Woggle-Bug play[9] are the only stories that feature him as the main character.

What did the Woggle-Bug look like? John R. Neill and Dick Martin drew him with two legs and two arms just like anybody. But the Oz books never say how many appendages he has. In The Land of Oz. Baum referred to him as an insect, so perhaps he really has six limbs like others of his class. Indeed, in the ”Queer Visitors” and in The Woggle-Bug Book, the illustrations show two legs and four arms. Later, he may have had an ap-pendagectomy, or Neill and Martin may only have been more disgusted by bugs than Ike Morgan or Walt McDougall (the illustrators, respectively, of The Woggle-Bug Book and the “Visitors” series), and so tried harder to humanize H.M.

Insects have wings, and the Woggle-Bug does too. But the only time we know of that he used them is in The Woggle-Bug Book where they acted as a parachute.

The publication of his Book marked the high point of the Woggle-Bug’s history. Although it is possible that he may have left Oz to collect data for his maps, no direct evidence shows that he ever again ventured far from the Emerald City, his university, or the road between. Yet despite his relatively quiet life, a few mysteries about him remain. Remember that at the end of The Land of Oz he became Public Educator; that office is never again mentioned in any Oz book. The next history, Ozma of Oz, mentions him as President of the College of Art and Athletic Perfection for young men and women who don’t have to or don’t want to work. Dorothv and the Wizard in Oz mentions the Royal College of Scientific Athletics.

By The Road to Oz, H. M. seems to have been demoted to Dean, and the school has become the Royal College of Athletic Science or maybe the Royal College for Scientific Athletics-both names appear. In The Emerald City of Oz, the school is the Royal Athletic College of Oz, which is nicely pictured on page 93. In The Magic of Oz and Glinda of Oz, the school is again the Royal Athletic College and the Woggle-Bug is its Principal.

Ruth Plumly Thompson and John R. Neill consistently called the school the College of Art and Athletic Perfection and had the Woggle-Bug as its Head. In Magical Mimics in Oz and The Shaggy Man of Oz, Jack Snow changed it back to Royal Athletic College (with the Woggle-Bug reinstated as Principal). Then, late in The Shaggy Man, he finally put the bug in charge of the College of Natural History.[10]

The Professor started popping pills in The Land of Oz when he rescued his friends from the jackdaws’ nest by swallowing Dr. Nikidik’s wishing pill. Throughout his life, he has continued his pharmaceutical fixation with such ingestibles as learning pills and language pills (frequently called Tablets of Learning, and once called Patent Educational Pills). The purpose of the Learning Pills was avowedly to enable the students to devote their entire time to athletic exercises. In The Lost Princess of Oz (p. 77) the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman took a course of the pills (though how these particular gentlemen could swallow and assimilate them is not specified). But who invented them? In The Emerald City of Oz, the Woggle-Bug said, “We use the newly-invented School Pills, made by your friend the Wizard.” In later books when the pills are mentioned, the Woggle-Bug himself is said to be their inventor. If so, then perhaps the Wizard was only the manufacturer (he did hold a license to practice magic and the bug did not). Or maybe the original pills were largely humbug and the Woggle-Bug improved them so much that nothing was left of the Wizard’s version but the idea. Of course there is no question that H.M. invented the Square Meal Tablets.[11]

A more difficult and confusing contradiction is found in the Woggle-Bug’s own nature. He is sometimes kind, sometimes haughty, sometimes gracious, sometimes rude. His first magnified action was a polite bow that surprised some little girls who were not used to mannerly insects. (During the ensuing commotion, he jumped off the screen and escaped.) A bit later, he courteously presented the Scarecrow with his card. Both incidents indicate good breeding. Still, in Glinda of Oz. we read, “Professor Woggle-Bug was not a favorite outside his college, for he was very conceited and admired himself so much and displayed his cleverness and learning so constantly, that no one cared to associate with him.” But in Dorothy and the Wizard, Ozma considered him “so learned that no one can deceive him,” and in The Scarecrow of Oz, we find that “The Professor was an interesting talker and had very polite manners.”

All we can conclude is that at least some of the time he was not regarded very highly by his non-academic acquaintances. He was not always popular inside the college, either. In The Magic of Oz, the Woggle-Bug was so proud of his Square Meal Tablets that he fed them to his students, who became so violent “that the Senior Class seized the learned Professor one day and threw him into the river—clothes and all.” Poor H.M. couldn’t swim and had to wait three days until he was caught by a fisherman. Although the Woggle-Bug wanted Ozma to punish the culprits, she was not very severe; she herself had refused to eat the Tablets.

The only consistency about the Woggle-Bug is his inconsistency. Despite his contradictions and his occasionally despicable behavior, he has done a great deal for Oz. The learning pills (no matter who invented them) are a boon to students at the college (no matter what its name): the scholars can spend more time on athletics and still learn. During his career, H.M. has composed a song, “The Shining Emperor Waltz” (The Road to Oz), and two poems, “Ode to Ozma” (The Road to Oz).and “Ode to Ozana” (Magical Mimics in Oz)—said to be very similar. He got credit for the map of Oz published in 1914 as endpapers in Tik-Tok of Oz, although there is no mention of his actually having charted it himself. He is an advisor to the queen. He also wrote many books, including the Chronicles of the Land of Oz (The Shaggy Man of Oz), and undoubtedly was involved in other scholarly works that are not yet mentioned in published Oz history.

Among the most pretentious citizens of Oz, the Woggle-Bug is one of the few with both faults and virtues. Most of the other people in Oz books are either terribly good (for example, Dorothy or Ozma) or terribly bad (the Nome King or Ugu the Shoemaker). Although Baum didn’t make the Woggle-Bug a very likeable character, he did make him a very human one.

[1] L. Frank Baum spelled it Woggle-Bug, Wogglebug, Woggle Bug, and WoggleBug.

[2] Frank Joslyn Baum and Russell P. MacFall, To Please a Child (Chicago: Reilly & Lee, 1961) p. 24. This book also describes how L. Frank Baum was once talking with a young girl who had found a bug. She asked Baum what it was and he replied, “A Wogglebug.” She was fascinated with the word, so he decided to use it in a story.

[3] Mr. Woggle-Bug did not become a professor until The Emerald City of Oz.

[4] Eventually, the piglet was found to have fallen into a large, narrow-necked vase. Eureka had not eaten it after all (although it had been her-intention to do so).

[5] “What Did the Wuggle-Bug Say?” by L. Frank Baum and Paul Tietjens, reproduced in The Baum Bugle, Christmas 1969, was used to promote the “Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz.” “Mr. H.M. Waggle-Bug, T.E.” by Baum and Frederic Chapin, reprinted in The Baum Bugle, Christmas 1973, was written for the play.

[6] H.M. did not “officially” meet Dorothy until Ozma of Oz in 1907.

[7] This episode is one of the few that were kept in the much-abridged and rewritten version of the series entitled The Visitors from Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Lee, 1961), illustrated by Dick Martin.

[8] Wait McDougall, the illustrator for the series said, “A deal was made between the Philadelphia North American, Riley (sic) and Britton, Frank Baum and myself to produce a ‘Wizard of Oz’ page weekly, Baum stipulating to furnish ideas, but he almost totally failed to produce.” (see the erudite article on McDougall by LC. Dobbins in The Baum Bugle, Spring 1968).

[9] The play’s plot is a composite of The Land of Oz and The Woggle-Bug Book.

[10] Aithough this College might be merely a branch of the Royal Athletic College.

[11] Professor Woggle-Bug’s Square Meal Tablets were certainly a wonderful invention and a great boon to anyone experiencing a shortage of food or going on a long trip where food might be scarce, or to anyone too lazy to enjoy eating. We first learned about the tablets (about the size of a small fingernail, but containing a six-course dinner -soup, fish, roast meat, salad, apple dumplings, ice cream, and chocolate drops -yes, I know that’s seven but Baum evidently didn’t) from the Shaggy Man in The Patchwork Girl of Oz, p. 134. Shaggy, an habitual traveler, always carried the tablets with him. The Woozy, who tried one, was not properly appreciative of Shaggy’s way of thinking; the beast wanted something he could chew and taste. On the other hand, later on in the same book, the Lazy Quadling, who found it “such hard work to chew,” was willing to help build a raft when promised six Square Meal Tablets for his aid. The Scarecrow actually gave him eight tablets when the man complained that he had been overworked.

Authors of articles from The Baum Bugle that are reprinted on the Oz Club’s website retain all rights. All other website contents Copyright © 2023 The International Wizard of Oz Club, Inc. All Rights Reserved.